This year, we read books like maps. In the over 125 reviews that Full Stop published in the past twelve months, one can discern the traces of expeditions: attempts to become oriented in a world that time and time again fails to correspond to our finest moral coordinates, the careful uncovering of narrative tools and pathways, indulgent but necessary fantasies of arrival. These missteps, recalibrations, and moments of bold trailblazing are particularly evident in this selection of some of our favorite pieces, from Hannah Klein’s intensely personal evocation of the anxieties of environmental crisis provoked by reading Gold Fame Citrus, to Patrick Disselhorst’s explication of the tactical deformations of language and form that enable John Keene to make space for a variety of visions of blackness in Counternarratives. These reviews may not locate precisely what it is they sought when they first embarked, but in the process of trying they nevertheless perform a serious, constructive engagement with that unwieldy collection of texts called contemporary literature.

This is, after all, the project that has motivated the editors at Full Stop through the first five years of our existence. And we are so grateful for the support of our contributors and our readers who have sustained us and helped to make Full Stop a vital space for promoting and exploring the important, imaginative works published by small presses, in translation, and written by young writers. We hope you continue this journey with us into our second half-decade. And if these accounts of readers reading feel important, exciting, even necessary, the kind of writing you’d like to continue to see, consider donating by following the link below.

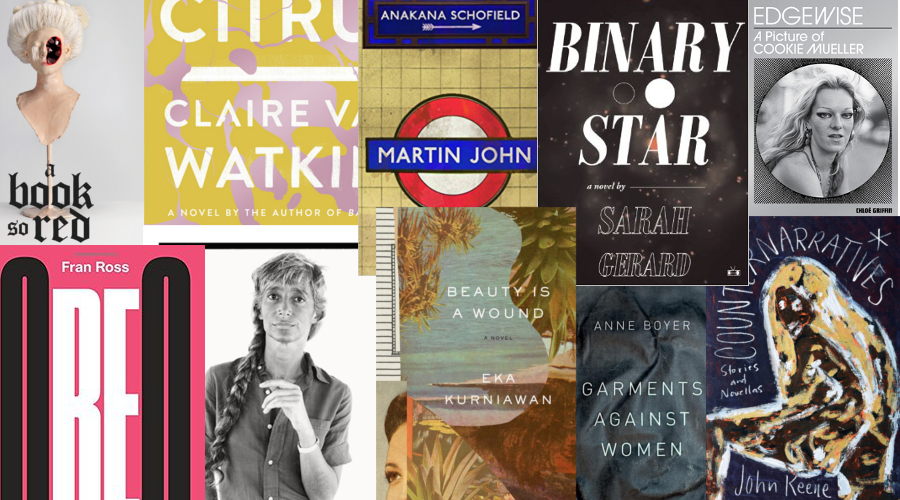

Gold Fame Citrus — Claire Vaye Watkins

Reviewed by Hannah Klein

When I first caught wind of the apocalyptic proclamation that the state’s water supply was going to run out within the year, I wrote it off as alarmist clickbait. We’re definitely in trouble, just not in this (my) lifetime. I’m just not that kind of environmentalist, I can’t be — paranoid ranting offends my cultural sensibilities.

Reviewed by Caren Beilin

Levy torques, tortures, cliché — “I have so much to give,” like a line unspooled by machine from a bachelorette on television, now fucked in its pronoun, something we give, this love, staple and I, I and thou staple, to Horst. Changing the automatic language of cliché, of rote representation, of reality television, changes — explodes, opens — the possibilities for desire. Desire expands, complicates (to staples, to other women) when you fuck with clichés.

After the Tall Timber — Renata Adler

Reviewed by Sho Spaeth

There is, in [Adler’s] criticism, a kind of wonder at the lengths to which some writers will go to avoid saying plainly whatever it is they have to say. In mining these obfuscations, Adler makes the larger point that this problem is more noticeable in institutions, and institutional voices, which are more concerned with protecting or burnishing their reputations than in the truth. Of Adler’s many complaints about The New York Times, one of the most striking is her analysis of the way the paper publishes corrections of the most minor errors, which is a kind of sleight of hand meant to reassure its audience that it takes the facts seriously, even while it papers over larger questions about its reporting.

Beauty is a Wound — Eka Kurniawan

Reviewed by William Harris

What does Kurniawan’s book gain from magic realism, or magic realism from the book? It’s — at least to English readers — a new local hybrid, blurring Indonesian folk art with a global style: a further tack on the map. It helps us see more clearly the sharpening of a world-spanning constellation, how literary forms travel, become imported and exported, dock and assimilate and gain complexity in a time when borders open to capital, close to people, and do something murkier with ideas. As for the book, the form makes possible political allegory, the literal haunting of history; it gains form, I want to say, but more to the point it does what’s so fascinating about magic realism — taking influences from all across literary history and showing how within them lay the possibility for a new way of writing and thinking.

Garments Against Women — Anne Boyer

Reviewed by Anna Zalokostas

I tried to write an essay but failed. My essay failed because I couldn’t figure out how to weave the threads together in any wearable way. I kept getting stuck on something, especially at work: the edge of the cash register drawer, the lock on the rare books case. The essay that failed was mostly about the sticky substances suspended on the surface of social life, the kinds of feelings I’ve become obsessed with examining because of what they tell us about power relations: aimlessness, alienation, boredom, illness, depression, anxiety, shame.

Counternarratives — John Keene

Reviewed by Patrick Disselhorst

Keene’s collection admits a variety of tales, a variety of visions of blackness that do not subscribe to one unifying, categorical whole. There is a sense that, by tapping into the variety of time periods and locations, an entire story has yet to be told. By proffering documents and by reimagining history, fiction presents the opportunity to distort the official narrative — in playing with recorded histories, one can re-record, re-inscribe. As if, in a collection, these pieces comment on, build upon one another; each resonating out of the loss or the high or the ambiguity that the previous piece is anchored in.

Reviewed by PT Smith

The strange multitude of ways that desire manifests itself is essential to Binary Star. In a simple way the narrator’s anorexia is a denial of desire but seen more complexly, it is an essential desire. In one of those openings, what I continue to want to call poems, she admits “I want no part of my body touching any other part.” The reality of what that means is haunting, in the context of stardust, something philosophical, a desire to be nothing, to be absence. It is desire.

Martin John — Anakana Schofield

Reviewed by Jessica Alexander

Perhaps, Martin John is not so much a character as a caricature of masculinity, a figure that, though, granted a privileged position in meaning’s labyrinth, is, nevertheless, caught in his own circuit, fumbling with his zipper.

Reviewed by Seth Cosimini

I am the readerly Janus head of stuffed and starved, pleased and disgusted. Ross certainly came, but how about you, reader?

Edgewise: A Picture of Cookie Mueller — Chloé Griffin

Reviewed by Hestia Peppe

I feel like identity is much more useful for speaking about the past than the future. It’s when we compromise the complexity of our reality by submitting to language, and therefore identity, that stories can be told. Even to speak about the future is actually to imagine a point, beyond the future we are describing, from which we can look back.

This post may contain affiliate links.