How much weirdness is acceptable and what becomes gross or nauseating? What is the limit? I find it interesting for the body too. . . What’s the limit of grossing out a reader and having someone stay with a story?

Our sense of genre has evolved so intensely that you can use them quite quickly to bring in other ideas or ideas that we might not expect from a detective story or an action scene. That disjuncture or that conflict can be interesting and comical.

Whenever I’m beginning something new . . . I’m always looking for a constraint of some kind. Some kind of blueprint inside the work that tells me how it works.

The idea that I would have to be silent about an experience that I had because it would make other people feel uncomfortable . . . just felt obscene at a certain point.

I thought to myself, I haven’t gotten better. I still have OCD. There’s no answer; there’s no resolution. The book is just going to be “this is my brain, this is what happens in my brain, the end.”

I don’t think it would ever be possible for me to disentangle poetry and friendship in my life—friendship is so central to my composition and editorial process, and poetry is so central to basically all of my relationships.

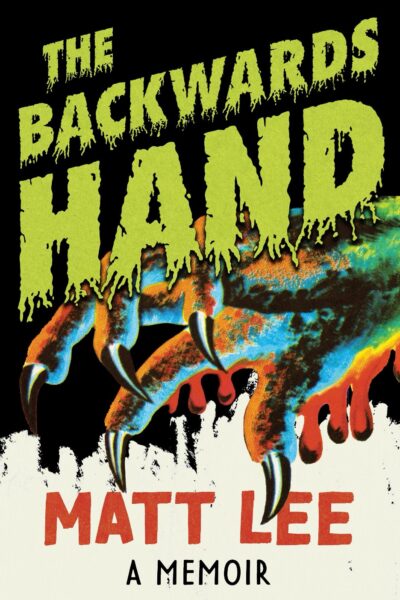

Richard Scott Larson & Matt Lee

We often look into a mirror to check our appearance and make sure we’re presenting ourselves the way we want to be seen by others, and the memoir as a mirror allows us to control our self-presentation even as it also involves acknowledging our flaws, the things about ourselves that we can’t ever change.

I don’t know how I would feel if I read myself as a character in someone else’s work. It must be—what’s that feeling? Disorienting, maybe.

When it comes to indie music in Zagreb and Belgrade . . . those times were truly inspired. It was great to have a front row seat to all that . . .

In the course of living, are we acting? In the act of remembering, are we editing life? And when we first began to watch movies, did the act of watching films become the way we experienced our memories?