In August of 2023, Erin Malone and I connected over Zoom, comparing notes on the changing weather in our respective parts of the Pacific Northwest. We talked about Malone’s new poetry collection, Site of Disappearance, which revisits the childhood death of Malone’s brother alongside the concurrent abduction and murder of two boys in her Nebraska hometown. As a reader, I was struck by the way Site of Disappearance treats submerged memory, using poetic image to first evoke and ultimately transform frozen, wordless forms of personal and communal grief. In the weeks after our conversation, we edited the Zoom transcript of our conversation for length and clarity.

Jessica E. Johnson: I was hoping to get started, maybe you could talk a little bit about the genesis of Site of Disappearance: How long were you thinking about it? What prompted you to write it? What were some milestones and challenges in the composition?

Erin Malone: I think I actually started writing it in 2015, but the idea began forming earlier than that, around the time my first book was accepted for publication in 2013. My son was about ten years old when these memories started coming back to me: a group of kids at a bus stop, the feeling of being watched, stranger danger. Memories of junior high. In my notebook I started to jot down little notes, memories and events, actual events that happened in the town where I’m from. But I didn’t start working on anything really until 2015, which is when I felt released from the first book [Hover] because it was finally published. Then I was able to make that leap to the next project and I applied for a Jack Straw Fellowship. Jack Straw is here in Seattle and they help writers learn to perform their work as well as give them a platform. That’s really where the project launched. I thought that it would be maybe a long poem and I was going to make a chapbook consisting of one long poem or something like that. And then it became clear to me that it needed to be many poems. I needed to get at it from different angles.

The long poem that you were originally thinking of—there is a really long poem in the book. Is that the long poem you had in mind initially, or did it look totally different in the original conception?

It was very different. Just now I looked back over my earliest notes and it surprised me to see that I had something from the poem that became “Archive,” which is the long poem you’re referencing. I think it might be from early 2014. I didn’t think that I was working on it then, but I must have been playing with lines and repetition:

Where the field assumed

A shape,

The searchers found

Their answer.

I didn’t realize that I had that so early. I thought it came later.

What were some milestones and challenges along the way?

My challenge was taking this great big emotional thing and figuring out how to put it into words, you know, how do you say it? At the beginning of “Archive,” I use a quote from Chase Twitchell that says, “You can’t translate something that was never in a language in the first place.” That to me puts it perfectly.

I had to investigate to find out which memories went where. I sat down and worked out a timeline with my mom and dad. Sometimes they remembered things I didn’t know, and vice versa. I had to find out what was fact and when things actually happened. My parents helped me piece together our family story as it intersected with the local tragedies.

The actual historical facts about what was happening in the community—I had to verify those separately, by digging into the archives. I think one of the biggest challenges I had was, first of all, there were two different boys who were taken and murdered. That history overlaps with my family’s. But I had to be very careful of the sensational aspect. One of the most important things is respecting the stories of other people and to not run over that. And the other thing is, you know, this book is about my brother, who died from a heart defect when he was eleven. The day he died was the day the first boy was found.

Writing this was hard for many reasons. In earlier versions of the manuscript, I had trouble because the boys’ stories were too forward and I needed the narrative of my brother and my son to come forward more. It was about balancing those, and that was really tricky.

That makes so much sense to me, the task of balancing. One of the ways that the book is really successful is that it stays within the realm of what’s happening in your own consciousness, in the making of memory and the experience of memory. So that seems to be, as in the title, the place where meaning is made is within you. And the poems center and focus there and that’s where all of these stories come together.

Thank you. That’s nice.

You asked about milestones. Having the work supported by residencies made all the difference. My first was at Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts located in Nebraska City, Nebraska. That’s only about forty-five minutes away from the town where I grew up, and that gave me access to the landscape of my childhood. To go back there and live for a month. . . . I got to return to the nature of the place. I’d be sitting outside and I’d hear a cardinal. We don’t have cardinals up here in the Pacific Northwest, or not that I know of.

No, no, we don’t.

(Laughs.) There are different trees and the grasslands and it all helped me, to put myself back in that place. To return was very important, because it gave me back a physical world I had forgotten.

Site of Disappearance was a finalist for Alice James and the National Poetry Series.

Yes, I think it was a finalist for about a dozen contests. It took a long, long time to find its publisher, but those honors kept me going. What really helped me was when I started sending to open reading periods rather than contests, because some of those editors gave me specific feedback that I could use to revise the manuscript. I’m thinking in particular of Lisa Ampleman at Acre Books, your editor and press. I sent it to her and the comments she gave me made me see the book differently. I did a major overhaul of the book at that point, pulling some poems, writing new ones, and reordering. I think that was 2021.

I felt pretty good about the book then. But waiting—well, it got to the point where I was thinking, at the end of last year—I said to my husband, if this next round of contests and open reading periods doesn’t pan out, I just don’t know what I’m going to do with it. I can’t go any further with it. I felt like I’d found its best form. And then, thankfully, Mark Harris at Ornithopter Press picked it up in February 2023.

We both studied—I think—with Linda Bierds at University of Washington. Did I make a wild assumption there?

No, you’re 100% correct.

Good! I’m starting to think that place is maybe something of a nexus for poets working with the image or interested in poetic image, and I guess I’d like to first ask if you agree with that. I also want to talk about the work of poetic image in grief.

It’s an interesting observation that you made about our school. We have a rich history here in the Pacific Northwest. I didn’t think about it in terms of image until you said that. I agree. And I would say that Linda in particular has this deep regard for subject, whatever she’s working on. A lot of times it’s an external stimulus, a painting that she’s looking at or a photograph, and then she tells the story of the photograph and the photographer or the painting and the painter. For want of a better way to say it.

With that regard is also this thought about what’s happening just outside the frame. What’s outside of, you know, the frame of the painting or just in the corner of the painting. In her latest book, The Hardy Tree, she has Alan Turing looking at a painting by Pieter Brueghel, “The Bird Trap.” She describes ice skaters and the sounds their blades make on the ice, but she’s also concerned with two objects: the bird trap, and at the very bottom of the painting a hole in the ice that’s barely perceptible, and none of the skaters are aware of it. She imagines Alan Turing looking at this painting and noticing both the bird trap and the hole, while waiting for some officers to arrest him. So, she moves image and story together. It’s an amazing poem.

I was really influenced by Linda early on. I was a grad student when I was in my mid-twenties, pretty young. I studied with Linda, Heather McHugh, Colleen McElroy, David Wagoner, and Rick Kenney. David would recite poems to us. I learned to pay attention to sound in his class, and form in Rick’s. And Heather—I didn’t know how to put it into practice until much later, but she wanted us to take risks. So, learning from all of them, that blend, I think it shows up in my work. Does that make sense?

For sure. It does make sense.

I also wanted to ask about the relationship between image and grief. This collection deals with a personal loss, but also loss that’s experienced by a community. That happens to overlap the personal loss and time and space. And the poems are rendering and depicting these combined disappearances in really precise detail and resonant images. I found myself thinking a lot about the role that detail and image play and personal and maybe communal grief. I would love for you to talk about, if you can, the work of image in the poems, what’s being enacted with image at the “site of disappearance.”

So much of my memory is flattened, two-dimensional. It’s like snapshots of things that happened. I think the work of the image is to try to animate those memories—give them movement, and by doing that, you know, move the thing forward. Like if you think of putting stills together in order to make a movie, right? I’m doing that stitching in between so that the reader can run it all together and see the narrative.

Because for me, the grief is very—it’s very silent. Those silences are what frame the grief, at least for me, being that young. There was a lot of silence in the house, and a lot of silence around me at school. When I went back to school, which wasn’t very long after my brother died, no one knew how to talk to me. I remember being really angry at that. I mean, now I understand it—how do we, what do we say to people who are grieving a loss that deep? It’s hard to bridge that. For me, the image frames that silence and then the repetition of the image moves it.

Do you feel like that movement or transformation sort of helps the grief move from a silent and stuck place?

Exactly. Yes, very well said. Thank you. Some of the last poems I wrote for the book actually came from thinking, all right, how do I move the story forward? One of them is about my mother on the stairs ahead of me, called “Slide.” In the poem I’ve just come in the door, following my mother, and I’m asking her a question. And she won’t turn around, because when she does she’ll have to say the words, that my brother has died.

I love that one.

Thank you. I feel like I tried to write that poem for—I mean, obviously it’s been in my memory since I was thirteen years old. I probably started trying to write it thirty years ago. I would try, I would attempt a few lines. One time I wrote a villanelle. I tried to find a form, but nothing was successful. I think I needed all the other poems in the book to inform me how to write it. By the time that poem came along, the book was almost finished.

I call it “Slide” because it’s like what I was saying before, a still photograph in my mind of my mother ahead of me on the stairs. What was in her mind? What was in my mind? And I had to advance us. After all this time, I’ve finally moved us past that, I hope.

The other poem I was thinking of that came late is “Spell,” in which I imagine my parents still in that house I grew up in, that we left when I was fourteen. It’s heartbreaking to think how young they were. In the poem they’ve been asleep for all of these years and now I’m the adult. In the fairy tale I’m the one who can come and wake them up.

I just wanted to note: when you were talking about Linda’s poetics, you mentioned the way she uses artwork or a scene made from history, for example. I think the work of hers that I’ve read most recently is The Profile Makers, and in that one, sometimes there are scenes made from the speaker’s own life and family too. And it’s interesting the way that you’re talking about the creation of “stills” in Site of Disappearance and the way they create frames. The creation of a frame allows you to name what exists inside of it, but the creation of that frame also allows the poem to gesture at what’s outside of it. And also the compiling of all of the frames tells a story—in this case a complex one. So that might be part of the connection I was sensing.

You said that so well just now. That’s a great compliment, to have my work compared to hers. Thank you.

I was also interested in the ways parenthood is present in the book, the ways it reveals griefs papered over. How did you find it propulsive or challenging to write through parenthood, especially with the scene-making we were just talking about, because again, there’s someone else’s life in play?

Well, it’s hard. I mean, my son, as far as I know, I don’t think he’s read my work. But I’ve told him the story of this book. He knows he’s a big part of it. This is one of those things that as a parent I’m conflicted about. And my parents—I don’t know how they’re going to feel about seeing themselves portrayed. I said to them, I’m telling the truth, but I’m also creating the characters. It’s not the true you, necessarily.

I don’t know how I would feel if I read myself as a character in someone else’s work. It must be—what’s that feeling? Disorienting, maybe. My parents have been really supportive, you know, they’re like, okay, well, we understand. They haven’t read the book yet, they haven’t seen it. We’ll see what they say.

About my son, I’ve used him in the work since he was born. He’s never said to me, don’t write about me. I think he knows that I can’t not write about him. He’s central to both of my books because his growth was the force of change in me. Going forward will be different because he’s an adult now, living a life outside of mine.

But you’re right, it brings up the question of ethics. Most of the time working on this book I was worried about the ethics of using the boys’ stories. They’re not mine to tell. But on the other hand I was a character on the periphery. The boys’ stories were central in the community, and then my story, my family story was over here. [Gestures.] We were the little figures on the side of the frame. My brother was buried next to the first victim just by coincidence.

Was that painful at the time? I didn’t get the sense that it was from reading the book. But hearing you talk about it now, I wonder if it was—to have your story be a little figure, within a big picture. Or no?

No, because our grief was so huge, and we were in the center of that. In my family story, those events were on the periphery, even though it was all over the news and everything. But we were very close to it. I remember how at school the teachers were watching us and how we couldn’t go anywhere and no one wanted us to be outside on our own. I was thirteen, I knew what was happening, but my personal grief eclipsed it. It was only as an adult that I could see that no one else knew about my family’s grief, except our friends.

And in the book, it certainly seems like your son reaching the same age awakened all of these memories for you in some way or gave you a sense that there was something there that you had not maybe processed. Is that accurate?

That is accurate. I had forgotten these boys. I’d tamped down those memories, I guess, and it was only when my own son was reaching adolescence that I started having these flashes and concerns—just, you know, like something not feeling right in my body. That sixth sense that something was wrong, that something was following me. That’s when I started asking my parents about it. I remember specifically sitting up with my mom very late into the night talking about it: when did this happen? Okay. And then when did that happen? Listening to her recollection and trying to piece the timeline together. My father and my younger brother also helped nudge the memories.

Then I had to go to the archive to look up the facts, and it was really very eerie to find physical documentation—the picture of the boy who was found on the day my brother died and my brother’s obituary right next to it.

Wow. I didn’t realize those details were literal.

Yeah.

At the beginning, I named Linda as maybe some poetic lineage, but I would be interested to know how you would trace it and what you were reading and watching when you were writing Site of Disappearance, or if there are teachers or traditions that you think the book flows from or that you see your work continuing?

By the time I started writing I’d already read Maggie Nelson’s Jane: A Murder. Do you know this book? It’s a story about her mother’s sister, who was murdered in her early twenties. It happened before Maggie was born, and her family doesn’t talk about it. Then she finds her aunt’s journals and starts asking questions. The murder was unsolved, and she’s trying to piece it together. The book is a mix of excerpts from her aunt’s diary, dreams she has about her aunt and about the murder, and poems.

I do remember re-reading Jane with an eye toward what it’s doing and how. I think that was a good example for me to have. Also Beth Bachmann’s first book, Temper. I haven’t read the book in a long time, but I think it’s about a sister who is murdered.

Anne Carson’s Nox is a book about a brother who disappeared from her life, and she creates an archive from old photographs and letters. It’s beautiful; she’s replicated them so the reader can remove pages from the binding, which isn’t a binding but a box. She’s bridging a distance by doing that, and I think we can feel her grief in the details, like pages that have been marked by water glasses. It’s a tactile experience.

Later on, when I was further into my own book, I was reading Laura Da’s Instruments of the True Measure, for the way she tells a personal story and reimagines historical events. I love her work. I taught that book as part of a class called Animating the Archive. We also studied Natasha Trethewey’s Native Guard, Kathleen Flenniken’s Plume, and Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas.

Yes, “animating the archive” is a good phrase for that research-based strand of Site of Disappearance.

I really enjoyed that class. During it I was still writing and revising my book, which was a great thing because though I was leading the class, we were all in it together. Talking to the students about how they interpreted the texts helped me, too. So that was really nice.

Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas just blew me away. The erasures and the silences that come from that book were definitely instructive to me when I was writing.

Jenny George. Do you know The Dream of Reason? I love that book. There’s grief there, but some joy and lightness too.

I was influenced by different sources. I watched a YouTube video of Bartholomaus Traubeck who invented a turntable to play a tree’s rings. It’s very otherworldly. That was my soundtrack as I wrote “I Tell My Son a Story,” about a man who’s haunted by what he’s done. Other imagery in that poem came from my experience of the landscape at UCross in Wyoming. The artists at that residency were doing stuff that filtered into my poems.

What about your work as an editor at Poetry Northwest? I’m curious to hear if that had any influence, if having what I imagine as a constant stream of contemporary poems in front of you helps refine your sense of what is yours to offer, or if it muddies the waters? Did those years of editing shape this collection at all?

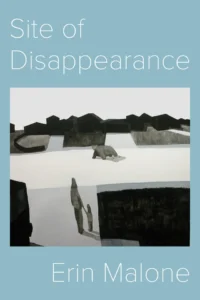

I don’t think so, not directly. Although the cover for the book came from one of the most delightful tasks that we do as editors. My co-editor Aaron Barrell and I got to choose cover art for the magazine. Ryan Molenkamp is an artist in Seattle, and we featured a painting of his on one of our covers. If not for that, I might not have seen this image, which is from an early series he’d started but abandoned. The work so eerily illustrates my hauntings and anxieties. I’m thrilled he let me use it for my book.

Working on the magazine helped hone my skills in terms of constructing an order for my book, because every issue involved arranging poems in such a way that they’d echo or chime or otherwise reflect on each other. That was a really important step in my development as a writer. Also, I loved seeing just how much great work is out there that we might not have an inkling about, you know? It’s kind of like, we live in our neighborhoods and go about our daily business but the whole world is out there. I feel that same way about poems. Here we are working on our own, and we know a few books and we know a few other poets, but there are so many still to discover, this exhilarating plurality of voices. Reading submissions to Poetry Northwest gave me that window.

Jessica E. Johnson is the author of the book-length poem Metabolics, the chapbook In Absolutes We Seek Each Other, and the forthcoming memoir Mettlework. She lives in Portland, Oregon where she co-hosts the Constellation Reading Series.

Born in New Mexico and raised in Nebraska and Colorado, Erin Malone is the author of Site of Disappearance, Hover, and a chapbook, What Sound Does It Make. Site of Disappearance was a finalist for the National Poetry Series; other recent honors include the Coniston Prize from Radar Poetry and the Robert Creeley Memorial Prize from Marsh Hawk Press. A former editor of Poetry Northwest, Erin lives on Bainbridge Island, Washington and works as a bookseller.

This post may contain affiliate links.