The following is an introduction to the latest issue of the Full Stop Quarterly, edited by Full Stop Fellow Nico Millman. You can purchase the issue here or subscribe at our Patreon page.

This issue of the Full Stop Quarterly, “The Cultural Politics of Land,” assembles nonfiction essays, original poetry, book reviews, and interviews that illuminate the role of literature, art, and other cultural practices in contemporary social movements related to the land. These contributions move across various languages, geographies, and struggles, with a focus on those in Palestine, Kashmir, and India, as well as those in Indigenous lands across the Americas. The communities in these different parts of the world face connected forms of political repression, which are themselves buttressed by racial and religious chauvinism, the political apparatus of the nation-state, and neoliberal free trade agreements in a global capitalist economy. Across these contexts and in these land-based struggles, cultural production has functioned as a unique political tool.

In the light of the truly global nature of these struggles, this issue for Full Stop Quarterly asks the following: How do diasporic writers and artists involved in organized political collectivities challenge projects of land dispossession threatening their ancestral homelands? Do such cultural forms circulate through corporate publishing and multimedia channels; or, because of their political nature, do they follow different patterns of circulation and translation? How do these cultural producers experiment with various artistic and literary traditions to express affective relations to the land? In what ways do cultural expressions about the land enliven social movements based on territorial reclamation, ecological justice, and anti-imperialism?

The contributions to this volume help us think through such questions. The essays in the first section, “Multimedia and Education Against Dispossession,” address how Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities in the Americas generate political collectivities through their creative engagements with print, multimedia, and educational technologies. In their essay, “Freedom Sounds and Care Practices in Anti-Extractivist Mapping,” Ivanna Berrios draws our attention to an experimental sound project by a Latin American audiovisual collective, Maizal, which documented the ongoingly disastrous effects of a multinational mining company on Nangali, a Peruvian pueblo (community) in the Andes mountains. The members of Maizal created a series of recordings that overlay the sounds of wildlife, water, and mining machinery from the region with snippets of their interviews with women of Nangali who discuss their involvement in land defense initiatives for over twenty years. Berrios’s “close listening” of these recordings reveals the possibilities for art collectives to issue political dissidence through “sonic cartographies,” or the mapping of the ecological, cultural, and political histories of land via the compilation of particular sounds.

In a similar way, the words offered by Making Worlds Bookstore and Social Center Collective elaborate upon the collective function of art, publishing, and education, and imagine some of the ways we can harness such resources in the service of undoing dispossession. The members of the collective run a nonprofit, independent bookstore in West Philadelphia, and the space itself is dedicated to supporting cultural programming for Black and Brown communities, including teach-ins on environmental issues in the area, reading groups on anti-fascist self defense practices, compiling local oral histories about the 2020 uprisings, and much more. Their manifesto, “In Our Times, a Space, In Our Struggles, a Future: A Vision for the Worlds to Come,” enunciates a style of political consciousness that understands grassroots media networks as central to sustaining long-term struggles for environmental, racial, and economic justice.

The contributions in the second section, “Poetry and the Horizons of Liberation,” demonstrate the ways that poetry constitutes a terrain of struggle in the context of dispossession, particularly in the sense that they offer powerful imaginative avenues to grieve lands lost and to contemplate possible futures amid a catastrophic present. Omar Zahzah, in his review essay “Giving Language to the Language of That Which Cannot Be Constructed: George Abraham’s Birthright and the Insurgent Poetics of Palestinian Liberation,” discusses how a new generation of young Palestinian poets have turned to previous models of revolutionary writing upon coming of age in the wake of the Oslo Accords, a series of bureaucratic agreements between the state of Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization from 1993–1995 that effectively negated the Palestinian right to return to ancestral homelands. Zahzah discusses the creation of the “Unity Intifada” in 2021, a coalition of Palestinians across the globe who are rejecting the divisive terms introduced by the Oslo Accords for understanding Palestine and Palestinian identities, before analyzing an interview between two such poets, George Abraham and Mohammed El-Kurd. Then, he moves into a careful analysis of George Abraham’s 2020 book of poetry, Birthright, and interprets their experimentations with redaction and with writing sentences in reverse as poetic disruptions of Zionist conventions of language, history, and time. Zahzah also remarks upon the profoundly personal elements of Abraham’s poetry, particularly their “crisis of confidence as a Palestinian poet,” a dynamic that cannot be separated from their relationship to land. As Zahzah elaborates, Abraham resolves this crisis through their continued imaginative encounters with the works of other Palestinian writers, a process that we as readers come to understand as central to nourishing the revolutionary imperative of collective Palestinian liberation.

In their dialogue, “The Poetics of Congregation amid Dispossession,” Abdul Manan Bhat and Partha P. Chakrabartty meditate on the relationship between Urdu poetry, Persianate literary traditions, and the meaning of political liberation. Bhat and Chakrabartty begin by describing the history of their friendship, which began when they both met at a protest in Philadelphia that challenged the annexation of Kashmir by the Indian state in August 2019 (a protest that I, too, attended!). Thereafter, they became collaborators and interlocutors; Chakrabartty would translate Bhat’s Urdu-language poetry into English, and they have presented their work together at various venues across the globe. In the dialogue presented in this volume, they discuss some of their favorite ghazals, a Persianate poetic form that has a long history in the South Asian subcontinent. They reflect upon the ghazal as “an invitation to congregate” and dwell on the significance of such a gesture in the context of the ongoing military occupations in Kashmir and in different parts of the world. You will encounter one of Abdul Manan Bhat’s original and previously unpublished poems in this volume, titled “Alam.” The poem has been made available in both the original Urdu script and in English, which was graciously translated by Partha P. Chakrabartty.

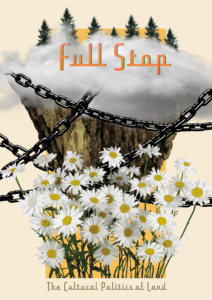

You will find the impressive artwork of Mariyeh Mushtaq on the cover and in the pages of this volume. This cover art is an experimental rendering of a landscape. It features a suspended chunk of earth partially shrouded in mist upon a faded yellow, almost colorless, background. Treetops poke through the mist and lend depth to the image. Steel chains, emerging from within the mist and outside of the frame, crisscross the middle ground of landscape. A cluster of daisies bloom upright in the foreground. The viewer’s eye moves from the deeply textured images of earth, mist, chains, and flowers to the untextured negative space in the background. In my view, it is possible to read such a juxtaposition as an allegory for grasping both the particular and universal dimensions of land dispossession, a task that this volume undertakes by turning to writers who transmit such stories from different parts of the world.

The contributions in this volume remind us of the multiple ways that writing and artistic collaborations are simultaneously political processes. These cultural practices also reconfigure what the political ‘means’ in community-based struggles related to the land. And so, I invite you to linger in the words offered to us by the writers of this volume—I hope you learn as much as I did from them.

—Nico Millman, December 2022

[Purchase the issue here]

This post may contain affiliate links.