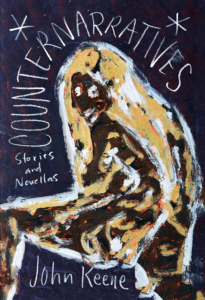

John Keene’s Counternarratives, a collection of stories and novellas, contains fictions that are inspired by historical figures, places, and a multiplicity of distinct events spaced around a singular force — the African diaspora following the introduction of the slave trade to the Americas. The narratives move along a roughly chronological timespan, the stories spanning from the early 17th century to the present. To varying degrees, they play with the reader’s knowledge of history; a history understood from the vantage points of colonizers, missionaries, nations.

The title Counternarratives can be understood as describing the way these stories actively push back against instituted narratives, forcing fictional flights of the imagination in order to pin down and ascertain certain truths that have been effectively lost. For the narrator of Keene’s Annotations, an elliptical autobiography told in prose poems, enraptured by books and reading, “dreams consequently assumed the contours, colors of the interior of the town’s modest main library.” In Counternarratives, it often seems as if visits to the library have been subsumed by dreamlike reveries which transform the dominant narratives contained in these spaces. In an interview with the Paris Review, the poet Susan Howe describes some of the elation of discoveries made in libraries that complements Keene’s approach: a visitor to the library may delight in “discovering accidental originals or feeling like you’re pulling something back. You’re rescuing and bringing them into the light.” Because, for all of Keene’s imaginative powers, he is pulling from sources and building from them. Howe subsequently paraphrases William James, contending, “In times of trauma and crisis a door is opened to a place where facts and apparitions mix.” It is in that space that Keene crafts these stories of complex individuals often treated as footnotes or bit characters in the lives of other people. There are stories inspired by, among others, Catholic missionaries in Brazil and the American South, W.E.B. DuBois and George Santayana’s first encounter at Harvard, a portrait of the meeting of Edgar Degas and the model for his painting, Miss LaLa at the Cirque Fernande, and the suicide of a turn-of-the-century minstrel composer.

Similarly to Howe, Keene often emphasizes the visual aspect of a text, pointing back to its manifestation as a physical object. “Blues” imagines a brief moment in the lives of two early 20th century literary figures. In it, a tryst in New York between Langston Hughes and Xavier Villaurrutia is expressed through a series of sentence fragments offset by ellipses: “ . . . softly . . . softly . . . they lie . . . beside each other . . . in the crepuscular dark . . . holding tight . . . night pouring in . . . to stir the blueback shadows . . . somewhere out there dawn . . . on the horizon . . . somewhere out there dawn . . . ” These words evoke discrete images simultaneously expressing the emotional force of the encounter while also referring to the text’s manifestation of itself as an object to be read. How words are composed and spaced shape how the reader interacts with them. Keene’s fragments adorn the elliptical breaks, sidling against each other without ever truly touching. Verbs like “pour” and “stir” and an emphasis on the dawn “on the horizon” suggest a tactile blurring at the limits. These bursts of poetic imagery litter the page (indeed, as Keene writes, “they lie”). Each fragment, its own singular piece, is teased out through a demarcating ellipsis that never allows the individual parts to come into contact with one another. Though a work of prose, a complete sentence is never formed. “Blues” suggests, with implications for Counternarratives as a whole, that limits between the text and lived experience can birth characters, places, and situations where the potential, not necessarily the actuality, for radical interaction exists.

Other stories specifically emulate literary and historical documents: letters, history books, journal entries, and newspaper clippings. “An Outtake from the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution” resembles a chapter from a history book — replete with subheadings, maps, and quotations from documents seemingly culled from researching original sources. “Gloss, or Our Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows,” is contained entirely through a single footnote to a work of fictional history of early Roman Catholicism in the early American Republic. In both instances, Keene strives to exploit that initial framing in order to emphasize the individual rebelliousness channelled within.

In “An Outtake,” it appears at first glance that the narrator of the historical text has adopted a neutral, measured tone, “In January 1754, Mary, a young Negro servant to Isaac Wantone, wealthy farmer and patriot of the town of Roxbury, Massachusetts, gave birth in her master’s stables to a male child.” Yet, notes of subjectivity steep in. Zion, the male child born to the Wantones is constantly in escape from bondage and, set against the backdrop of the oncoming revolutionary war, functions as an ancillary rebel. American revolutionaries are unable to frame his struggle for freedom through anything coherently resembling their own. After Zion is returned to one of his several owners, he again revolts, the narrator methodically noting that he:

fled towards Boston, where he stole two cakes of gingerbread, a package of biscuits, and a pint of milk out of a horse-cart heading north. He secreted himself in a nearby marsh. He was discovered a week later, arrested and housed in a local jail. He swiftly broke out by eluding his guard . . . and headed south by southwest along the lesser roads and trails. The local authorities again captured, tried and imprisoned him, not only for his crimes but for his defiance of the social order, yet his realization of his own personal power had galvanized him, making life insufferable under any circumstances but his own liberation.

While describing the “facts” of the situation, Keene ends the paragraph with a glimpse into Zion’s psychology, his incessant need to escape demanded, seemingly, by the inescapable logic of the social order. As the narrator gives a humanistic description of Zion’s desire to flee, the text’s objectivity is turn over, examined, and made confused.

Carmel, a young slave girl trapped in a convent in rural Kentucky in “Gloss,” draws pictures that shape the exterior world. Her artistic sensitivity is inextricably linked to her situation. Carmel’s drawings are crude and marked by strange details, “jarring juxtapositions of nefarious symbols, such as snakes, rainbows, hatchets, fish, coffins, swords, and unidentifiable abstractions.” The images, according to a Catholic priest that visits the family of the daughter she dotes on, “showed that their creator possessed an inestimable capacity for evil.” Carmel’s subject matter, drawn from books and images she’s seen, her early life on a plantation in Saint-Domingue, and her relationship with the Catholic church is melded with “figures, such as loas and spirits, from the folkloric accounts she had heard from her mother and older elders.” In this blending, seemingly divergent systems of thought coalesce due to her specific location. The content of the text, again, mimics the form. In the fanciness of a footnote, tangents merge; the story switches from an omniscient third-person narrator to a collection of fragmented journal entries written by Carmel to, finally, clear and concise first-person narration told from Carmel’s perspective. Combining styles inverts the inherent sanctity of the text just as Carmel’s drawings reject artistic standards placed on her without her consent.

Whereas, couching texts like “An Outtake” and “Gloss” in a (seemingly) objective format and inserting characters who undermine that objectivity into those forms gives these stories a tinge of rebellion that echoes the protagonist’s individual revolt, several of Counternarratives’ stories are written without a visual framing. Orality is central to a story like “Rivers.” In it, the Jim of Twain’s novel begins the story in conversation with a newspaper reporter who would much rather he speak about his adventure with Huckleberry Finn than his heroic efforts in the Civil War: “What I’d like to hear about, the reporter starts in, is the time you and that little boy . . . and I silence him again with a turn of my head, thinking to myself that this is supposed to be an interview about the war and my service in it.” In place of a specifically visual dimension (a footnote, a letter, journal entries that define the other stories), “Rivers” relies on an oral framing that suggests loss or the need to re-interpret: there is a need to fictionalize the fictional in order to examine the truth of white attempts at representing the period.

Keene’s collection admits a variety of tales, a variety of visions of blackness that do not subscribe to one unifying, categorical whole. There is a sense that, by tapping into the variety of time periods and locations, an entire story has yet to be told. By proffering documents and by reimagining history, fiction presents the opportunity to distort the official narrative — in playing with recorded histories, one can re-record, re-inscribe. As if, in a collection, these pieces comment on, build upon one another; each resonating out of the loss or the high or the ambiguity that the previous piece is anchored in.

In “Mannahatta,” Jan Rodriquez, the first settler to New York and New York State, is described after his immediate departure from the Jonge Tobias, a Dutch trading vessel, and his landing on the shore. Keene writes:

There was always the possibility that one of the first people, one of whom he expected to appear at any moment, though none did, or some nonhuman creature, or a spirit in any form, would untie the markers, erase the hatchings, thereby erasing this spot’s specificity, for him, returning it to the anonymity that every step here, as on every ship he had sailed on, every word he had never before spoken, every face he had never seen until he did, once held.

Keene’s long sentence meanders and searches for something to grasp ahold of. But, the lack of specificity, the lack of demarcations, is inherent to his character’s predicament. Rodriquez, Keene alerts the reader in the introductory note to the story’s initial publication in TriQuarterly, as “a mulatto . . . of San Domingo,” the son of a Portuguese father and African mother, complicates the reader’s understanding of New York. The first settler of the city, simultaneously African, Dominican, and Latin American, is underrecognized, but in this story, he emerges, “never to return to the Jonge Tobias, or any other ship, nor to the narrow alleys of Amsterdam or his native Hispaniola.” Rodriquez functions as our introductory figure to the text — a man of African descent arrives as a settler, and along with him, an alternative understanding of how the Americas were initially constituted. Keene trains the reader to be alert to openness; to view things singularly involves a lack of foresight in watching figures or situations brush up against received knowledge.

Keene, digging through the stacks, finds under-read figures, underexplored ideas, and then crisscrosses genres, themes, and tropes. Forms are malleable. Inventive works of fiction allow one to stretch the limits of books and books’ claim to representing our reality. In exploring a number of subjects through the prism of the African diaspora, Counternarratives proffers a series of stories in which religion and spirituality, art and language, violence and subjugation, homosexuality and eroticism, may shine through a panoply of voices.

Patrick Disselhorst is a writer currently living in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.