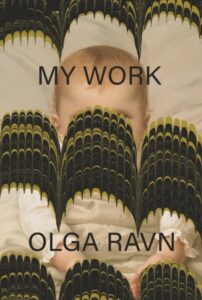

[New Directions; 2023]

Tr. from the Danish by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell

Olga Ravn begins her newest novel, My Work, with an unexpected question: “Who wrote this book?” The narrator is quick to assuage her startled reader. She wrote the book, of course. Only, did she? The unnamed narrator tells us that she has found a journal written by a woman named Anna, written during Anna’s pregnancy. The narrator is cagey: she tells us that she’s not sure whether Anna is just a reflection of herself, but also that she is not Anna, and that we should not allow ourselves to believe that they are the same person. If you flip to the acknowledgements of the novel, you’ll find that Anna’s journals have been reconstructed out of the character Anna Wulf’s notebooks in Doris Lessing’s 1962 novel, The Golden Notebook. But none of this is the point. The point, as far as the narrator of Ravn’s novel is concerned, is determining exactly how to represent Anna’s story. She confesses to us that she has put Anna’s pregnancy at the center of the narrative, an irreversible transformation of Anna’s reality that we, as readers of this novel, will never be able to full understand, having just met her. It seems to the narrator that writing a novel is an act of supreme power, and she wonders whether or not she has the right to claim this power. After all, what is an omniscient narrator if not a minor god, creator of chronologies, conductor of the rules of reality? In My Work, Olga Ravn plays with the sinister anxiety about what it means to render something real.

Born in Copenhagen in 1986, Ravn often writes about women’s bodies, the nature of labor, and how work affects social and personal relationships. For Ravn, the pregnant body becomes a microcosmic environment tensely defending itself against the violent onslaught of the global conditions of capitalism. Her book, now translated into English by Sophia Hersi Smith and Jennifer Russell, was originally published in Danish in 2020. Smith and Russell have translated a number of works of fiction and poetry by Danish writers such as Tove Ditlevsen, Marianne Larsen, and Rakel Haslund-Gjerrild. Clearly, they have experience in adapting works by Danish women about women in precarious circumstances, and their collaborative effort interprets Ravn’s sense of humor, tonal leaps, and narrative slippages into English.

My Work takes place in 2017–2019. In her journals, Anna writes about the election of Donald Trump in the United States. In her home country of Norway, the conservative party wins the general election. Anna, constantly on the verge of going broke, frantically makes lists of the countless products that need to be bought during pregnancy, ahead of the birth of a child, and afterwards, to take proper care of the child. Ravn delivers these facts to us in a staccato rhythm of the prose that takes short-range, direct shots to punctuate the building tension in Anna’s mind. It’s no surprise when she is eventually diagnosed with anxiety; we are already primed to her way of thinking. The medical notes provided by the hospital nurses and caretakers feel cold and estranged, like field notes from ethnographers studying some reclusive community.

But when the novel takes place outside of the hospital, it comes across less as a record and more as a manifesto. At times, the narrator seems to be writing a declaration of the rights of domestic caregivers. When she describes her own reading of Anna’s diaries about giving birth, she demands, “Is her writing about her body and home not precisely workplace literature?” Ravn’s maternity manifesto arrives at a moment when the value of domestic and care labor has come under particular scrutiny. This year alone saw the publications of Minna Dubin’s Mom Rage: The Everyday Crisis of Modern Motherhood, M. E. O’Brien’s Family Abolition: Capitalism and the Communizing of Care, and Alva Gotby’s They Call It Love: The Politics of Emotional Life. All of these books demand new solutions to the exploitative system of domestic labor particularly imposed on women in western societies, and historicize the idea that a mother’s ultimate purpose is to provide care at the cost of their individual identity.

Ravn’s place within this historically-oriented turn to women’s work, as well as the prolific space of autofictional novels about motherhood that mirror her novel (like Sheila Heti’s Motherhood) speaks to the still-growing sense of urgency to reimagine gestational labor and its implications for how a person is recognized by others and themselves. Ravn petitions us to continue trying to define the ways in which life and labor intertwine, and to find a way to extricate the figure of the woman from this convention. Her novel is not a straightforward story about two people’s experience of pregnancy or a claim to their rights as workers. In My Work, there is no home without the economic structure that exceeds it, there is no writing without a product. Something is always being created in the process and assessed for its significance, one that has been historically undervalued and requires a specific language to deliver it into existence. Ravn’s novel makes the case for how she believes that the child-rearing body should be put to words: fragmented, and perhaps somewhere beyond the page it first appears on.

It’s important to remember that at the outset of the novel, the COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t happened yet, but the world is on the brink of historical and economic catastrophe—the narrator can feel it in her gut. Her work, she tells us repeatedly, is writing, which she is unable to do in any meaningful capacity while she is pregnant, and especially not once she gives birth to the child and spends every moment ensuring that it stays alive. How can she raise a child and accomplish her work, both of which seem integral to her very being? How can she keep herself together in this world? With these questions, the narrator leads us to believe that her concerns are about the stories we tell about pregnancy, childbirth, the experience of being a mother, and all the feelings that arise in these moments. But Ravn elegantly dispels the assumption that her novel can be any kind of answer or guidebook to maternity, or a set of emotionally restorative suggestions. Instead, its about the project of writing and the many forms that writing a self can take.

Time, too, is a mystery that plays with our expectations of straightforward narration. Anna’s chronology bends and twists, and only strictly follows the growth of her child. The narrator decides to put Anna’s pregnancy at the middle, not the beginning, and not the end of the story. Whose story? Is it Anna’s, or this other, shadowy voice? And, who reads this story? We, as readers, are let in on the secret of Anna’s journals by our narrator, who wants to keep herself a secret. As readers, we have the urge to fill in the blanks, untangle the twisted parts, and try to keep the story on track. My Work requires us to resist that urge. It requires us to agree to the convoluted nature of the project of rendering oneself real, whatever that means. In this novel, motherhood punctures reality and transforms it into something new, something that fuses with the responsibility of existing and the responsibility of making another existence possible.

Through Anna and the narrator’s pleas to return to their work and the many journal entries, letters, poems, and dialogues that link their voices, the novel challenges us to think about our fictional and real selves, the selves we imagine ourselves to be, the selves we can never know because we can only experience ourselves from the inside. This is to say, who wrote these words? Was it the self I think I know, or the person you think you know by reading this? Was it the self I conjure when I don’t want you to know what’s going on inside my mind? Maybe it was all of us? And, who is reading these words? The person I imagine reading them, or the person whose eyes are scanning this page right now? Maybe it’s both of you? Ravn’s novel doesn’t let us slip away from these doubts, nor does it offer us an answer. Always skeptical, My Work teaches us to ask more precise questions.

Ravn’s novel is an exhausting as much as it is an exhaustive journey through an anxious child-rearing mind. My Work sprawls outwards from its pages; the fragments of poems and diary entries and letters settle into me as I read. At one point, the narrator says she is fighting against psychological realism, but I am already too deep into the hall of mirrors of her consciousness to argue otherwise. I wonder if the novel is changed by my reading of it, just as I am changed by the novel’s reading of me. In her journal, Anna writes, “How to see oneself as anything other than an image, spoken into being out of nothing?”

Lora Maslenitsyna is a writer from the San Francisco Bay Area. Currently, she is pursuing a PhD in Film and Media Studies and Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University.

This post may contain affiliate links.