[World Poetry Books; 2023]

Tr. from the German by Greg Nissan

As an American poet and translator living in Poland and raising two children bilingually, where hearing phrases like “jeszcze strawberries!” or “I don’t wanna kąpiel!” are the norm, it’s no surprise that the Polish-English mashup in the English title of Uljana Wolf’s German work, kochanie, today i bought bread, grabbed my attention. In her introduction to the volume, Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort sharply observes, “Uljana Wolf enters German literature with a Polish word”—kochanie, which can mean “honey,” “sweetie,” “darling”—and “the Polish word inside a German mouth is a site of mutual history, mutual silence.” While Mort’s alliterative pairing is poignant, there is much more than “mutual history, mutual silence” that cleaves these two countries. The eighteenth century partitioning of Poland; the atrocities of World War II; the strategically important and shared Oder River; living under the Iron Curtain; a remapping between Germany’s eastern and Poland’s western border that resulted in the forced relocations of entire populations. The forest holds particular import within the social imaginary of both countries, whether it’s via the lingering influence of folk tales and Romanticism or demonstrated in Netflix’s recent Polish series aptly titled The Mire (Rojst in Polish). It’s precisely in the electromagnetic forest of family relationships and porous international borders that Uljana Wolf’s economical and sparse poems chart their terrain.

In addition to being a poet, Uljana Wolf is a translator from English and Polish who has brought the work of poets such as John Ashbery, Erin Mouré, Yoko Ono, Cole Swensen, and others into German. Kochanie, today i bought bread is her third full-length collection to be translated into English. This volume was translated by Greg Nissan, the recipient of an NEA translation fellowship whose previous translation credits include the unflinching War Diary by Yevgenia Belorusets (New Directions, 2023). Nissan also served as the poetry editor for SAND, a well-known Berlin-based English-language literary journal, and is the author of The City Is Lush With / Obstructed Views (DoubleCross Press). Like other books in the World Poetry Books catalogue, Wolf’s is bilingual with the poems arranged en face. Such a language pairing—German and English (also a Germanic language)—benefits from the visual-linguistic mirroring, the effect of which can be amplified by the echoes of words or phrases that are repeated and reconfigured in many of Wolf’s poems. For those inclined to pause and scan the verso, an opportunity to cross into linguistic borderlands always hovers, much like Wolf’s poems map and mine various liminal spaces.

The book is divided into four sections: “displacement of the mouth”; “subplots”; “kochanie, today i bought bread”; and “krzyżowa, companions.” The titular poem from the opening section, “displacement of the mouth,” brings to mind Paul Celan’s famous Breathturn: for both poets, the mouth and the speech act are capable of creating (or consuming) worlds.

the house shuts

its thin lips

in contrast the sky cracks

back its jaw : lightblue

close to uvula

over the dark taut

tongue-arch of the forest

In numerous translations, Celan has helped to familiarize many Anglophone readers with the way the German language can accommodate compression and conceptual friction via compound nouns, and the gesture can already be seen in Wolf’s “lightblue” and the “tongue-arch of the forest.” The poem’s house metaphor is in dialogue with Emily Dickinson’s “I dwell in Possibility – / A fairer House than Prose – / More numerous of Windows / – Superior – for Doors –.” But while Dickinson perceives an interior domestic space, Wolf couples her bird’s-eye view with the bodily.

The dreamlike convergence of the architectural with the corporeal concludes with the “breath unravel[ing]” and “speaking through / the sleeper’s lashes.” If Celan’s poetry has helped readers revel in the possibilities that compound nouns create, Wolf’s collection and Greg Nissan’s astute translations do something similar. The poem “recovery room II” describes a hospital stay as “the clammy / sleepcanal with murky nurses who line / the shore as judges and threaten you /with stricter fingerspritzes” where “only silence in the sluices / and sanitary purgatorrents nourish you.” Among the many fantastic neologistic nouns the collection provides, “purgatorrents” might be my favorite. When I encounter a word like “purgatory” in poetry, Dante’s Divine Comedy naturally comes to mind. Purgatory, for Dante, is not only the place where we pay the debts incurred for our sins, but where we remap our psychologies and become better versions of ourselves. The word “torrents,” however, is more in keeping with Dante’s inferno, a swelter visually rich in horrors. Nissan’s inventive portmanteau efficiently combines these associations and, in doing so, generates a sense of propulsive anguish.

In “deutsches literaturarchiv marbach,” Wolf views the museum’s archives—one of the most significant literary archives in the world, dating back to the mid-eighteenth century—as a site of historical erasure:

these boxes hold women

who could not be processed

hibernating in documents

contradiction sans diction

talk sans back

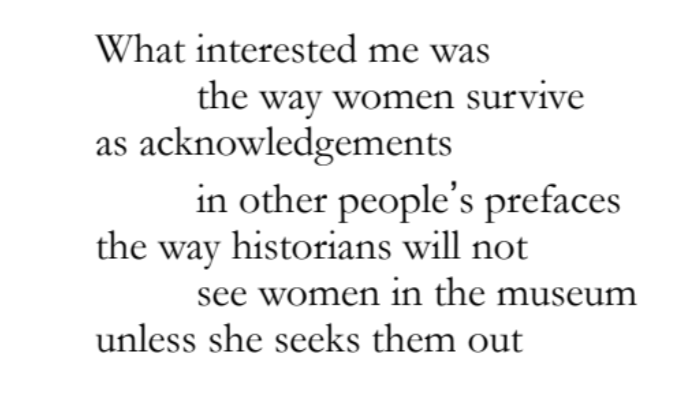

Such historico-poetic excavation echoes Sarah Mangold’s recent book-length poem Her Wilderness Will Be Her Manners, when Mangold’s speaker observes:

In Wolf’s telling, however, such relegation and neglect can be turned on its head, reclaimed and refocused into an accusatory glare: “my defiance is my instrument / my plunging silent.”

In the second section, “subplots,” domestic geometries give shape to the intimate scale of the poems and then extend outward through unnerving retellings of fairy tales and Shakespeare. Wolf uses a combinatorial and recursive structure, recalling the tintinnabuli accretion via minute variations of simple notes in Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s music or American poet Michael Palmer’s “Leonardo Improvisations”: “Can the / two be // told the / two bodies // be told / apart be // told to / part.” Like Palmer, Wolf eschews punctuation and presents a poetic conceit only to undo or reconfigure it. In the eight-part serial poem “my cadastre,” “my fathers / are simple men” and “are no simple men”; “my fathers / are simple surveyors” and not. The same is true for daughters, “my mouths / are simple daughters” and the inverse, “my daughters / are no simple mouths.” Such father-daughter dynamics and their relationship to their environment are continually shifting, positioning the reader in the roles of both perpetrator and survivor.

The four-part poem “wood lord shaft (Shakespeare titus andronicus)” uses scenes from Shakespeare’s horrifying tragedy to expose “the fuckrich bloodlines here conspiring” and lines such as “don’t say rome and roe don’t say dainty / doe chant hunt not pluck a flower plow” would scan as familiarly Palmer-like. It’s a common feature in Palmer’s poetry that the reader is enjoined to say, recite, call, or calculate various things (or negate them) within the music of alliteration or assonance: “can you calculate the ratio between wire and window, / between tone and row, copula and carnival / . . . or recite an entire winter’s words,” for example. But as the poems accrue in Wolf’s sequence, the use of alliteration and assonance propel the lines forward just as the couplets elegantly wrap the reader in menace:

daughterbodies flawlessly cut up

in ovidian style stria we saw you

in livestream lavinia we read and in all eyes

you were cataract, the dread-gray star

Among the more profoundly disturbing implications of the poems, “livestream lavinia” encapsulates the technological proliferation of the horrors of our times with devastating efficiency, makes us complicit in the marriage of violence to virality. It’s worth remembering that in the play, Lavinia, Titus’s daughter, is given away in marriage, only to be raped by Demetrius and Chiron, who subsequently cut out her tongue and cut off her hands, removing her ability to communicate. She is the embodiment of the unspeakable tragedy, which a “livestream” can now deliver to a global audience as disaster porn.

The imagistic title poem, “kochanie, today i bought bread,” provides an arresting summary for much of the book, the external other in the line “how the foreign / forms conversations” falls backwards onto the most intimate of domestic spaces, the bed:

only acclimating to

hill and dale the

way something hap

pens to form halves

atop a translatable

mattress

The haptic enjambment of “hap/pens” cleaves the couplet into an incidental pairing—“to form halves.” The solitary “mattress” is left to bear the visual weight of the previous lines as the pastoral “hill and dale” ripples into the warmth of those halves in an intimate space, which themselves read like a comment on poetic couplets dissected into constituent parts. What’s more, the bed imagery and inventive prepositional relationship again recall Celan: “in the bed / of my inextinguishable name.”

I’ve now lived one-third of my life connected to the city of Łódź, where much has changed in the intervening two decades, so I was touched by how Wolf captures the grey-grained, B&W quality of a vanishing era in the poem “łódź”: “an old photograph / in overexposed wind.” Other poems in this section pin us to specific locales, often where the names and languages have changed. For instance, “the ovens slept,” starts in Berlin, only to move to Glauchau—“ran a tremble as of traveling”—and then Malczyce (Maltsch), and Legnica (Liegnitz), towns where the “smoke from their mouths still hung / like night long stuck in our hair.”

The last section, “krzyżowa, companions,” is the shortest and offers a trio of poems, which makes sense—in addition to being the name of a village in Silesia—“krzyżowa” can also mean “cross-shaped.” Here the poems are haunted by longing, a phantom-like embrace:

till i’m left half-blind in your rib-light

and spinning beloved as if you had

woven the fogfence forever around

the bird your floating particle heart

The other two poems in this section, “to the dogs of kreisau” and “postscript to the dogs of kreisau,” both end with the concluding line divided by empty space, a pause and a wound. This effect is reinforced with the evidence of a dog bite: “my boots still bear the imprint / of your teeth—four stapler craters.” For the speaker, however, the souvenir provokes a note of resignation wrapped with command: “that’s how the world follows poetry at heel.”

For a book in translation, it’s a testament to Nissan’s work as a translator that this collection of Wolf’s poems offers an abundance of doorways for English-language readers. You don’t need to be steeped in the history of German poetry to engage with this book deeply and powerfully. Along with the poets I’ve already mentioned, Wolf’s poems invite an expansive dialogue with numerous poets. A sequence like “my cadastre,” which plumbs the depths of father–daughter dynamics within forested perils, are conversant with American poet Megan Kaminski’s Gentlewomen, where she chillingly writes, “a daughter who never returns / never disappoints.”

A number of the poems in Wolf’s collection informed by disturbing folk tales wouldn’t feel out of place in the company of Polish poets such as Hanna Janczak or Urszula Honek, whose work also largely avoids capitalization while interrogating complex family relationships in literal and metaphorical borderlands. The undulating borders and languages in Wolf’s poetry stand as a rebuke to incuriousness or insularity. As Mort reminds us, “Poetry remembers that, ultimately, history is a family matter” and, to borrow from Dickinson again, Wolf’s poetic house is indeed fair—but it’s also unflinching and has plenty of rooms for pointed reflection, redress, and even the most monstrous of relatives.

Mark Tardi is a writer and translator whose recent awards include a 2023 PEN/Heim Translation Grant and a 2022 National Endowment for the Arts Translation fellowship. He is the author of three books, most recently, The Circus of Trust (Dalkey Archive Press, 2017), and his translations of The Squatters’ Gift by Robert Rybicki (Dalkey Archive Press) and Faith in Strangers by Katarzyna Szaulińska (Toad Press/Veliz Books) were published in 2021. Recent writing and translations have appeared (or are forthcoming) in Poetry, Conjunctions, Guernica, ANMLY, Interim, Cagibi, Denver Quarterly, and in the anthology The Experiment Will Not Be Bound (Unbound Edition Press, 2023). Viscera: Eight Voices from Poland is forthcoming from Litmus Press in 2024. He is on faculty at the University of Łódź.

This post may contain affiliate links.