It’s an angry, frustrated joke, that idea that we might think about herstory rather than history, that every time we write about a woman or a woman writes about herself we have to bat away great cobwebs of nonsense about confession and biography. It’s not, I think, that we should write about women differently to address the balance — category and binary switching doesn’t really change the system — so much as that we must write about what came before us differently. I would prefer to have it said and done once and for all that these stories are the story of reality, that this is history — but as the impulse bursts into language the word is ashes in our mouths because finally that too is marked indelibly as his.

An understanding of those who came before is transmitted to those who come after. Not because they were truer than we are, not to prove we are wiser than them, but to wonder at lives we have no other way to access and to honour. Because a chain of bright connections got us here.

In Middle English, history just meant story. Somewhere in the collision between French and English is where that kind of crude pun about gender becomes possible. It’s always been the gallows humour of women that I cling to, but you can call it écriture féminine if you want to.

I feel like identity is much more useful for speaking about the past than the future. It’s when we compromise the complexity of our reality by submitting to language, and therefore identity, that stories can be told. Even to speak about the future is actually to imagine a point, beyond the future we are describing, from which we can look back.

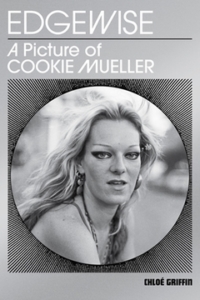

The first I knew of Cookie Mueller were the photographs of her by Nan Goldin: her face, once seen, stayed recognised. Though I didn’t know to look for them, much later her writing and her films found me, and I have no way of knowing what would have happened to me had they not but because they did I have more ways to be. Remember the time Cookie burnt her friend’s house down? It’s not the things she did, like, as if we should all just burn our friends’ houses down and not give a fuck, but the way these events are recognised in her writing. The way of living a life, the joy in the face of absurdity and struggle that has nothing whatsoever to do with ‘positive thinking.’ And at the same time it’s about her generosity in the telling of it, a generosity that her friends and lovers continue when they retell it, as they do through Chloé Griffin in Edgewise: A Picture of Cookie Mueller. Is this historiography? I prefer the idea of transmission.

I’d rather read the lives of saints than of philosophers and by saints I mean those who shine with presence and by presence I mean all the tricks of the trade and by tricks I mean tricks. I read memoir because everyone who’s gone before me is my teacher. When we read we are initiated into narrative lineage.

On the first page of Edgewise is a quote from Cookie: “Why does everybody think I’m so wild? I’m not wild. I happen to stumble upon wildness. It gets in my path.” The simultaneous dis-ingenuity and ingenuity of this statement is totally heroic. Cookie’s every bit as enigmatic as people often speak of Warhol being, but genius is not a type of person; it is experience — a way through. The past is just the way that the complexity of the present has to be made simple in order to imagine a future. Clear as water in a pool painted black is the genius of Cookie’s life, as clear in her own writing as it is here in the words of her loved ones, a way that did not exist until she made it do so; an example.

Cookie in her casket, a dayglo cross in her hands — a famous Nan Goldin image. I don’t know why that picture isn’t in Edgewise, or any others by Goldin. The reader is unlikely to miss them, wonderful as they are. Edgewise has a lot of other pictures, ones that I’ve never seen before, and they are all amazing. The all-American hero in black eyeliner with a baby on her hip. Patron saint of actresses, models, reality stars, and single mothers, black lined eyes winking out from every page. It’s almost an embarrassment of pictures, except it’s just glorious because embarrassment requires some kind of shame and Cookie banishes shame into nothingness. To be looked at, to have one’s image captured, is to shine.

A couple of years ago I worked on a very low budget movie with a lot of young actresses and after a screening a few months ago, in the Q and A, one of these girls, Yas, said that she never wanted to be an actress but that the experience of being in front of the camera had been the best way she could think of to learn how to make movies. This statement stunned me. The wisdom that comes from letting that attention hit you, from working that angle, so often described as passive, has been (though of course it isn’t usually), might be, can be intensely powerful and full of agency. To be inside of weird, difficult, hard-won experimental processes creates knowledge and power. We are taught to assume that to act is trivial and that to admire actresses is superficial because we are being taught to believe that the telling of stories is not power.

In about 2006 a girl who at some point had been/would be an actress/art director in underground movies, Chloé Griffin, was given and read Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black by Cookie Mueller, a girl who was at one point an actress in underground movies and who would later write about her own life. Chloé Griffin decided to write Cookie Mueller’s biography.

Almost a decade later the book that manifests has been not so much written as spoken and collected. Griffin contacted everyone that she could who had known Mueller, visiting and spending time with them, and she recorded what they told her, arranging their words chronologically in order of Cookie’s life. It’s like reading a transcript of a long rambling dream in which people speak from different interiors, to each other but not together. There is a disjointed together-ness that seems to come from Cookie. It makes sense from the outside! Perhaps what distinguishes sainthood from mastery is only a willingness to share the experience of extraordinary processes with others and to acknowledge that all creation is co-creation. The fact that this works here, that we can access it, is first Cookie’s and then Chloé Griffin’s very considerable achievement. To read the book is to observe the patterns of the traces and bonds created by a life, which, wondrously, are not obscured by editorialising or sentiment or paraphrasing on the part of the author, as so many people must have feared they would be. This is a book made with trust. Griffin describes her relationships with Cookie’s friends and family as friendships in their own right and honours them as such. She speaks of her work not so much as research process but as life decision, and her doing so does not so much privilege one of those over the other but allows both to co-exist.

Griffin has called Edgewise an oral history. Historically the relations between speech, as lives are told, and writing, as one might write a biography, have been constructed in opposition. That thing with Derrida and Cixous where they describe speech as having been given privilege historically over writing as if the written form had not been used to hoard power and secrets since its invention. That thing where we act like writing on the internet is less formal than writing a novel. As if it were not the combination of oration and written protocol with physical force that defines all the systems that enslave us. Really what we’re looking at is the triangular play between language, affect, and gesture. Experience is a landscape that can be both created and inhabited.

I prefer to describe celebrities as stars.

Cookie was a star: She was born and she died and these people so loved her that the light from her is still reaching us.

The point of fairy tales, in case you didn’t know, is that you must be pure of heart. The point of stars is that you want to be them. The point of saints is that when their bodies die they do not really leave us.

I want to say that when you read this book it’s ok to really love it.

Cookie says, “you will never die” and Cookie says ”you will be free” and she is right and she is.

Pure of motherfucking heart.

Hestia Peppe is an artist, writer, and sometime governess; a line tamer, a fire starter, and a keeper of connections. She lives in London.

This post may contain affiliate links.