There is a passage in Dante when he and Virgil, traveling through the Inferno, stop beside a man buried to his neck in boiling mud. He does not care to speak to them. He has his own problems. He does not want an interview. Dante actually grasps him by the hair and gets his story. Some sort of parable about reporting there. I think. In fact, I know.

— Speedboat

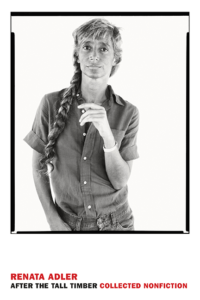

If there is any prose form that has been neglected, it is the well-constructed list. A fine example appears in the opening lines of “The March for Non-Violence from Selma,” the first piece in After the Tall Timber, a collection of Renata Adler’s nonfiction culled from previous collections, as well as some uncollected works. It begins like this:

The thirty thousand people who at one point or another took part in this week’s march from the Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal church in Selma, Alabama, to the statehouse in Montgomery were giving highly dramatic expression to a principle that could be articulated only in the vaguest terms. They were a varied lot: local blacks, Northern clergymen, members of labor unions, delegates from state and city governments, entertainers, mothers pushing baby carriages, members of civil-rights groups more or less at odds with one another, isolated, shaggy marchers with an air of simple vagrancy, doctors, lawyers, teachers, children, college students, and a preponderance of what one marcher described as “ordinary, garden-variety civilians from just about everywhere.”

Who were the thirty thousand people who took part in this historic event? A varied lot. How varied? Adler shows you, constructing a pattern of rhythmic blocks that serves to emphasize the variety on display. This is a kind of prose that deserves scansion as much as any poetry, and it is what any list demands to make it interesting. The final description, a quotation, is a phrase so fitting in the rhythmic and thematic scheme that it is hard to believe that it was uttered by an anonymous marcher, although it would be even more impressive if it was simply the invention of the author.

The next sentence expands the scene, adding to its variety: “They were insulated in front by soldiers and television camera crews, overhead and underfoot by helicopters and Army demolition teams, at the sides and rear by more members of the press and military, and over all by agents of the FBI.” Three sentences in and the scene has been definitively set, with a remarkable economy of language. Michael Wolff, who has written the introduction to After the Tall Timber, says that Adler’s prose “is quite unlike any journalism being written today,” and that “writing like this is really no longer practiced.” While he overstates the case, he is correct in his intended assertion — that this quality of writing is all too rare.

Unfortunately, the prose in the collected pieces is not as uniformly excellent; although it is hardly a criticism to say that the report on the march from Selma is the best in terms of prose rhythm. This may be in part because the book seems to have been structured to make the case for Adler as a critic, particularly as a critic of the press; criticism, after all, has different demands than, say, setting a scene, and Adler’s pieces demonstrate an enviable versatility. But this case becomes more pointed towards the end, with pieces collected from Adler’s book Canaries in the Mineshaft, which, as Adler says, “have to do, in one way or another, with . . . misrepresentation, coercion, and abuse of public process, and, to a degree, the journalist’s role in it.” It seems that each piece in After the Tall Timber, even those more concerned with reportage, was selected to portray Adler in this light, as if she were always a kind of ombudsman for the Fourth Estate. This is at once both too narrow and too simple; what this book instead shows is that Adler brings to bear on every subject an observant eye, a sharp ear, intellectual rigor, and a higher order of talent for writing, a combination that will inevitably uncover the errors of others — and discover them everywhere. If she is a critic above all else, it is more by default than due to intent, and if the press seems in each piece to be singled out for particular scorn, it is because Adler is particularly attentive to the misuse and abuse of language, which is a perversion of the journalist’s stock-in-trade.

In the piece describing the scene at the National New Politics Convention in 1967 in Chicago, Adler writes, “When words are used so cheaply, experience becomes surreal; acts are unhinged from consequences and all sense of personal responsibility is lost.” The degree to which language is corrupted (attendees using “genocide” to refer to minor acts of incivility) is so great that even the non-political guests at the hotel where the convention is held seem infected, referring to the event as a “student convention” and a gathering of “draft-card burners.” Misrepresentation runs rampant, Adler seems to say in every piece in the book, because imprecision in language is a cancer on the body politic, and it must be singled out, held up to the light, and excised.

The best illustration of this idea is Adler’s review of Pauline Kael’s book When The Lights Go Down. At the time, it was considered mean-spirited, at the very least impolite, to subject a colleague’s work to such intense scrutiny, as if to pay attention to a writer’s work is the ultimate offense. The piece is not, as some have claimed, vicious, nor does it seem motivated by personal animosity. As Adler says quite clearly, she merely turned her attention to the subject, and found not only the writing wanting (and offensive to her sensibilities) but also found to her alarm that the style had seemed to spread so far and wide as to become a school of its own.

The review marks, in After the Tall Timber, a shift to a more prosecutorial style, which coincides with a more definite shift in Adler’s role from reporter to critic, and the pieces consequently focus even more on the use of language. The first of many lists in the piece is as follows:

[Kael] has an underlying vocabulary of about nine favorite words, which occur several hundred times, and often several times per page, in this book of nearly six hundred pages: “whore” (and its derivatives “whorey,” “whorish,” “whoriness”), applied in many contexts, but almost never to actual prostitution; “myth,” “emblem” (also “mythic,” “emblematic”), used with apparent intellectual intent, but without ascertainable meaning; “pop,” “comic-strip,” “trash” (“trashy”), “pulp” (“pulpy”), all used judgmentally (usually approvingly) but otherwise apparently interchangeable with “mythic”; “urban poetic,” meaning marginally more violent than “pulpy”; “soft” (pejorative); “tension,” meaning, apparently, any desirable state; “rhythm,” used often as a verb, but meaning harmony or speed; “visceral”; and “level.” These words may be used in any variant, or in alternation, or strung together in sequence—“visceral poetry of pulp,” e.g., or “mythic comic-strip level”—until they become a kind of incantation.

She also likes words ending in “ized” (“vegetabilized,” “robotized,” “aestheticized,” “utilized,” “mythicized”), and a kind of slang (“twerpy,” “dopey,” “dumb,” “grungy,” “horny,” “stinky,” “drip,” “stupes,” “crud”) which amounts, in prose, to an affectation of straightforwardness.

The prose is more to the point, more workmanlike, than in the example from the piece on Selma (although not without its own gestures towards excellence: the rhythm of the opening operating around a spindle of enumeration; the almost fine line of “These words may be used in any variant, or in alternation, or strung together in sequence… until they become a kind of incantation.”), and this reflects that this list is for an entirely different purpose; namely, to build a body of evidence.

And that is what she does in piece after piece towards the latter half of the book, using the words of her subjects against them, whether it be Kael, Robert Bork, Kenneth Starr, Richard Nixon, or, particularly, The New York Times. Adler often points out misdirection that, once exposed, seems so obvious as to shame the reader. In her review of The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court by Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong, she criticizes the authors for proudly stating that the book is “based on interviews with more than 200 people, including several Justices, more than 170 former law clerks, and several dozen former employees of the Court.” Adler writes:

By the next page, we learn that the authors had “filled eight file drawers with thousands of pages of documents from the chambers of 11 of the 12 Justices” who served in the period under investigation. Then there is an apotheosis: “In virtually every instance [of what, they do not say] we had at least one, usually two, and often three or four reliable sources in the chambers of each Justice” (italics added). Apart from an occasion to smuggle that word “reliable” into what appears to be a quantitative statement, what can these vague enumerations mean? They mean that, at least, as regards number, the authors prefer their own pointless secret (how many) and implications of massiveness to precise statements of simple fact.

Even a casual observer of political journalism today, and of the tedious inside-scoop books it produces, will recognize that this bland enumeration of sources is still commonplace.

It is the “affectation of straightforwardness” and the “implications of massiveness” that are the main offenses in these two examples, and there is, in her criticism, a kind of wonder at the lengths to which some writers will go to avoid saying plainly whatever it is they have to say. In mining these obfuscations, Adler makes the larger point that this problem is more noticeable in institutions, and institutional voices, which are more concerned with protecting or burnishing their reputations than in the truth. Of Adler’s many complaints about The New York Times, one of the most striking is her analysis of the way the paper publishes corrections of the most minor errors, which is a kind of sleight of hand meant to reassure its audience that it takes the facts seriously, even while it papers over larger questions about its reporting.

Adler’s criticism is bolstered by the care and thoroughness with which she makes her arguments, and, for the most part, the degree to which she practices what she preaches. The most egregious sin Adler seems to commit is one of length; pieces from The New Yorker (particularly “G Gordon Liddy in America”) can go on too long, and contain the sort of extraneous detail meant to reassure the reader that the reporter in fact did some reporting (such as the exhaustive list of thirteen band names in the piece “Fly Trans-Love Airways”). But it is her respect for the institutions she criticizes, from the Supreme Court to The New York Times, that lends her criticism added heft. She is explicit about her admiration and respect for individual reporters, editors, justices, lawyer and political figures, all the better to make the urgency of her warning better felt: Even the best individuals can be led astray by institutional priorities, and the danger should be assiduously and unfailingly addressed, because as Adler convincingly argues in essay after essay (most notably in the ones on Nixon’s impeachment, the Supreme Court’s Bush v. Gore decision, and The New York Times’s treatment of the Jayson Blair scandal), institutional lapses can lead the eye astray to focus on some smaller truth while the larger languishes.

This last argument leaves a bad taste in the mouth, only because the larger truths Adler points to seem to have been ignored nevertheless. It may in part explain Michael Wolff’s assertion that “writing like this is really no longer practiced.” Despite Adler’s thorough documentation of the errors and excesses of, say, Pauline Kael’s style, that type of writing has proliferated and thrives — a recent restaurant review in a major publication contained this risible line about a chef’s cooking: “Now, to be precise, he is killing it.” It is no wonder then that Adler’s courage in challenging institutions is rarely emulated; even if there were someone somewhere with an equal intelligence and as fine an eye for language, what incentive could there possibly be to point out, in the strongest terms possible, the poverty of our collective language, only to have little to no effect?

It is heartening to see that Adler is enjoying a resurgence in popularity, and that many seem to find in her fiction a voice that seems as relevant to the current times as it did when her novels Speedboat and Pitch Dark were published. After the Tall Timber offers to the reading public a reminder that while she may be a fine novelist, it was through her journalism that she made her name. Yet both her fiction and nonfiction seem to share as an ideal the clarity of thinking that comes from the precise word, the apt phrase; language as a perfectible thing. And perhaps After the Tall Timber might serve a more useful purpose as an instrument for inflicting shame; to anyone who reads it, either in its entirety or piecemeal, this book says, quite clearly: You have not been reading carefully enough.

Sho Spaeth lives in New York.

This post may contain affiliate links.