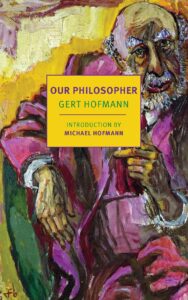

[New York Review Books; 2023]

Tr. from the German by Eric Mace-Tessler

“History leads nowhere”—at least, according to Herr Bernhard Israel Veilchenfeld, the titular philosopher of Gert Hofmann’s 1986 novel, Our Philosopher. It’s a curious remark in a novel about one man’s experience of persecution, violence, and terror in late 1930s Germany, published nearly fifty years after it’s set. Yet, the novel may bear out this thesis. Beginning and ending with Veilchenfeld’s death, it goes nowhere beyond its own opening sentence. And the text is largely void of historical or political references. As Michael Hofmann points out in his introduction, we don’t find any words like “Jew,” “Nazi,” “Brownshirt,” “Hitler,” or “Kristallnacht” in Our Philosopher. Hofmann’s novel isn’t a detailed, panoramic view of a society on the brink of war. What we get isn’t so much the forest of society, or for that matter the trees of individual psychology, but the sense that we’re somewhere outside of these usual categories. But there are hints of something else, what we would now recognize as history. Airplanes roar overhead, people disappear at night, rights are revoked. It’s the 1930s in Germany, after all, and we know where things are going. And so, in its own vague, uncanny way, Our Philosopher maintains a view of where it all goes. It is a grim, ominous fairytale.

The hero is Veilchenfeld, a gentle, aging professor whose learning is profound (he once knew Faust by heart). Veilchenfeld moves into a German town, where he attempts to write his life’s work but instead falls victim to violence and humiliation at the hands of the townspeople—presumably because he’s Jewish, though the text is never explicit. Our witness and narrator is a boy named Hans, the son of the town doctor who treats Veilchenfeld for a heart condition. Hans is drawn to Veilchenfeld for reasons that he doesn’t fully understand. His father calls Hans’s interest “pathological,” and there does seem to be something compulsive about it: Hans returns to Veilchenfeld time and time again, seemingly without explanation. Unlike most of their neighbors, though, Hans and his family are sympathetic, even kind, to Veilchenfeld. They have him over to their home once, Hans takes drawing lessons from him, and they are clearly disturbed by the events unfolding in their town. But they aren’t heroes or martyrs. They do little to confront the cruelty their neighbors inflict on Veilchenfeld, and when the father does stand up for the professor late in the novel, it’s too little too late. Several times, Hans and his parents even wonder whether Veilchenfeld would be better off killing himself.

Hans doesn’t always understand the significance of the events in his town (he’s a child, after all), and his limited understanding makes for a more chilling narrative. When he learns that a group of townspeople have attacked and humiliated Veilchenfeld in a local restaurant (notably called the Deutscher Peter, the German Peter), he earnestly asks his parents whether the police would allow it, unwittingly pointing out the gap between the real and the supposed ideals of his society. Elsewhere, however, Hans’s interest in Veilchenfeld is crowded out by his own childish interests—for example, when his parents anxiously discuss Veilchenfeld’s fate, he and his sister are more concerned with the prospect of ice cream. In these moments, Veilchenfeld’s total dehumanization gets mixed with the banalities and distractions of childhood; even Hans, who shows genuine interest in Veilchenfeld, somehow gets on with his life as Veilchenfeld faces torment after torment. And in Hans’s narration, we have little access to Veilchenfeld’s pain, which often appears indirectly—through his physical deterioration, for instance. When Hans reads one of Veilchenfeld’s notebooks, the rare unmediated glimpse of Veilchenfeld’s inner life stands out: “My humiliation. My lowliness.”

Our Philosopher isn’t the first or the only German novel to depict the experiences of a child during the war, but the novel’s minimalist style and flat tone perhaps set it apart from others. Hans is reserved and laconic, sometimes disturbingly so, as if the events around him had no real effect on him, or even as if (as in a fairytale) he had no interiority at all. Context is left out, facts are elided, so that the details Hans does report seem more like a collection of fragments stripped of their wider historical context, picked up and strung together without comment in the narrative. In that undeniably modernist way, Hofmann presents reality as fuzzy and distorted—if he’s presenting reality at all.

While Hans may be a child, the novel is no depiction of innocence or the loss of it—in Hofmann’s novel, there is no such thing. Hans is both a product and a member of a society that is trying to destroy Veilchenfeld. Hans comes from the town, and he belongs to it in a way that Veilchenfeld, the outsider, is never allowed to do. And by the end of the novel, Hans’s complicity is laid bare. Hofmann’s dark portrayal of youth caught up in the injustices of its time orients Our Philosopher toward the grim, disorienting post-war novels of Thomas Bernhard, or Robert Musil’s The Confusions of Young Törless, with its depiction of violence at an Austrian military academy shortly before World War I.

And, like Musil’s novel, Our Philosopher is no celebratory Bildungsroman. But why should it be, when, for Hans, growing up means integrating into a sick society? Veilchenfeld has a heart condition, Hans’s mother suffers from a series of health problems, and many of their neighbors are sick. The extent of illness explains why Hans and his parents have such a finger on the pulse of their town—Hans’s father is treating most of its people. Hans’s father knows, for instance, that farmhand Joseph Lansky despises Veilchenfeld to the point of obsession. In the sickbed vitriol Lansky throws at Hans’s father, we see the bare workings of a mind gripped by conspiracy theories, hatred, and an obstinate desire to ignore the truth. Like the other townspeople, Lansky can’t let Veilchenfeld simply be. They are preoccupied with him, even as they want him gone, “out of the world.” Hans’s father is also how the novel’s perspective widens, and we learn more about the town—that it’s poor, for instance. The roads are “criminally neglected,” and the next town over is called Russdorf, “soot village.” But even here, the novel doesn’t plumb the psychology of the perpetrators or claim to uncover the social conditions that led to fascism, as other post-war novels might try to do. Instead, the details are all just fragments of Hans’s world. They aren’t meant to add up to a whole.

Throughout the text, certain words and phrases of reported speech are italicized, and we see them as meaningless or inadequate. After the townspeople attack Veilchenfeld in the Deutscher Peter, for example, Hans’s father refers to the attack as “the assault,” his mother as “the infamous action,” and a neighbor as “an act of rage.” Their words and phrases are ossified, empty; they suggest a real event without conveying much about it. Elsewhere, the italicized speech consists of idioms (“someone’s hair is standing on end”) or hollow bureaucratic formulations (“to lodge a complaint”) that likewise can’t come close to describing reality or expressing a genuinely felt response to it. For Hofmann, who, like Hans, came of age during and after the war, the problems of language aren’t mere aesthetic hand-wringing, nor are they a reaction to war and the traumas of modernity. Instead, we see how the inability to authentically speak and communicate contributes to or enables the conditions of war, violence, and oppression in the first place. We feel not only deficiency and disorientation but, more importantly, loss and moral outrage.

So it’s no surprise when, after Veilchenfeld’s death, Hans passes by the philosopher’s coffin and simply says, “We’re sorry.” For Hofmann, through Hans, to offer reconciliation or hope at the conclusion of the novel, set just before the war, would have been disingenuous, even dangerous. But while the characters may speak a broken language, the same isn’t true of the novel. In its bare style, it is deliberate and powerful, especially in Mace-Tessler’s attentive translation. And, unlike Hans, the novel doesn’t offer an apology. Instead, it presents us with the suffering of one man (his humiliation, his lowliness) at the hands of his neighbors. In the face of power, that means something—a generation after the war, when Hofmann was writing, no less than today.

Noah Slaughter writes fiction and essays, translates from German, and works in scholarly publishing. He lives in St. Louis.

This post may contain affiliate links.