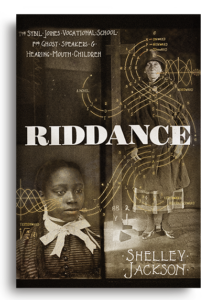

[Black Balloon Publishing; 2018]

[Black Balloon Publishing; 2018]

For all of her experiments with divergent media that are ultimately impalpable (her e-lit hypertext, Patchwork Girl, which is also essentially inaccessible unless you have the equipment to play a CD-ROM, on which the novel is now exclusively available), hypothetical (Skin, a “story” inscribed on human skin a letter at a time and that ultimately can never be read), or ephemeral (“Snow,” a story written on fallen snow — although it is being presented more permanently through photography), her conventionally printed novels are quite corporeal and amply realized. Half Life (2006) and her most recent novel, Riddance, are both long and comprehensively developed novels that allow the reader to settle in for a comfortable enough read, although in each case the story must be pieced together, and is not merely offered to us from a unified narrative perspective.

It might be most appropriate to describe both books as epistolary novels, albeit of the modern sort that extends beyond simply the exchange of letters as a narrative device to include other kinds of interpolated documents as well (additionally integrating visual effects, especially in Riddance), resulting in a form of collage as presumably Jackson’s preferred method of composing traditional prose fiction. (Likewise, her 2002 book, The Melancholy of Anatomy, is ostensibly a collection of short stories, but the stories are associated in a collage-like fashion, a series of vignettes organized by grouping them into sections representing the four humors and their respective origins in parts of the human body.) Thus these books are by no means regressively conventional in either form or subject — their subjects are in fact distinctly unusual — but they do adapt a formal strategy frequently enough employed previously by modern writers, in various permutations, that its use in both Half Life and Riddance is not disruptive of an “immersive” reading experience but really only adds a kind of mystery element to the novels’ quasi-horror plots: in addition to questions about how the extraordinary circumstances portrayed will develop and be resolved, questions pertaining to the exposition of those circumstances — how do the pieces fit together, how are they working to conceal as much as reveal? — become central to the narratives as well.

To describe these narratives as horror plots is not to classify them as genre fiction nor to denigrate horror elements as somehow unworthy in a properly experimental fiction. Jackson uses the tropes and trappings of horror lightly, adopting them not for atmosphere or specific plot devices but because the horror narrative prominently focuses attention on the human body, its traits and transformations, which has also proven to be Shelley Jackson’s most abiding preoccupation as a writer of fiction. Half Life borrows the imagery from a “mutation” film (“the incredible two-headed woman!”), but Jackson is not interested in exploiting this imagery for shock effects. Instead, she takes the potentially grotesque situation the novel depicts — an alternate reality in which atomic testing has created a substantial spike in the birthrate of conjoined twins — all essentially born with two heads on one body — as an opportunity to provoke reflection on our facile concepts of identity. In resolving to surgically remove the head of her sister, Blanche, who (she believes) has long been in a kind of coma, a prolonged state of uninterrupted slumber, is the novel’s protagonist, Nora, really proposing to murder another person, who, after all, shares one body with Nora, or is it merely the equivalent of amputation? Are Blanche and Nora actually two people? If so, which one gets to claim rights to their in-common body? For that matter, is it really “Nora” who speaks to us as the protagonist of Half Life, or is she at least as much Blanche, even before we learn that the latter has probably been more active all along than we realized?

Many readers of Half Life probably suspect all along that Blanche is likely not merely “dead weight.” Luckily, the novel doesn’t really depend on a surprise or trick ending. The narrative itself is insidiously humorous, despite the nature of the subject, and at times seems outright a satire of the rigid protocols of identity politics. (“Twofers” have become militant in defense of their rights, and demand observance of the proprieties in speech and behavior that uphold their status.) If it is relevant to the accomplishments of Half Life to call it an “experimental” novel, it is not because of its formal design but its creation of a “character” who complicates the very notion of unitary character in fiction — although its formal strategies certainly work effectively to help produce this effect. If printed fiction cannot attain the same degree of contingency and nonlinearity as hypertext, in Half Life Jackson nevertheless creates a character whose “true” identity may be whatever we decide it to be, and ultimately turns the narrative back on itself, encouraging us to perhaps reconsider everything we have read.

Riddance has its share of slippages and ambiguities, but while the story it tells is even more gothic than Half Life — set in a school for stuttering children in the early part of the 20th century, the school, we are told by the initial narrator, the “editor” of a scholarly compendium about it (the book we are about to read), “may have appeared on county maps in the vicinity of Cheesehill, Massachusetts, [but] its real address was in the crepuscular zone” — it is also more recognizable in its formal structure, a novel masquerading as another kind of text (Nabokov’s Pale Fire being just one example of this sort of fabrication, although the use of supposedly pre-existing documents as a formal device is a common enough strategy in horror fiction more generally). The editor, who at least fancies himself a scholar, offers us a collection of documents related to the Sybil Joines Vocational School for Ghost-Speakers and Hearing-Mouth Children, located in Cheesehill, the hometown of Sybil Joines, the founder and proprietor (although later directors of the school apparently also assume the founder’s name). It is called a school for “ghost-speakers” because Sybil Joines, herself a stutterer, believes that the dead make their presence known to the living in the speech — or non-speech — of those who stutter.

Although numerous kinds of found texts (as well as many photos and other graphic illustrations) are included in the editor’s collection, the two most important are undoubtedly the series entitled “The Final Dispatch,” which purports to be Sybil Joines’s own last communique, sent from the land of the dead, and “The Stenographer’s Story,” which tells us of the experiences of Sybil Joines’s assistant, an African-American student at the school named Jane Grandison, who transcribes the dispatch. (Jane Grandison eventually becomes the second Sybil Joines, although her status as an African-American at first leads her to express some skepticism about some of the assumptions at the school — how thoroughly white “the dead” seem to be, for example.) The circumstances surrounding Sybil Joines’s journey to the “land of the dead” eventually emerge — she claims in the dispatch to be pursuing a recalcitrant student she wants to bring back to the school — but the central interest of the novel surely lies in the exposition of Sybil Joines’s final encounter with this nebulous realm of paranormal existence she has spent her life — which the other entries in the collection work to elaborate — seeking to understand. The editor remarks in his introduction that through its layered organization, “this book can be entered at any point” (marking the printed text’s closest potential resemblance to a hypertext, although “The Final Dispatch” itself evokes hypertext in Sybil Joines’s descriptions of the fluidity of her surroundings), but this possibility is itself mostly virtual, since to approach Riddance in this way would really rob it of a forward momentum that clearly seems to be intentional.

Sybil Joines’s dispatch is the main attraction in Riddance as well because it features much of the novel’s best and most imaginative writing. “White everywhere,” she writes (or speaks, while Jane Grandison writes it down), in describing what she sees while pursuing Eve Finster, the errant student,

complicating into color, into form, fading again to white. White sky. White plains onto which white cataracts thunder down from an impossible height: souls pouring without surcease into death and roaring as they fall. The cataracts — the one stable landmark, the one feature on which all travelers report — one in such incessant motion that they seem immobile: one immense hoary figure, frozen in place, head bowed. Sometimes a bridge travels down the length of it: a fire in a shirtwaist factory, great ship sinking in icy waters. . . .

For all the apparent predisposition for the visual evidenced in her hypertext and alternative-media works (as well as the visual orientation of the passage above), both Half Life and Riddance show Shelley Jackson to be a poised and evocative stylist, one of the reasons both of these quite long books remain pleasurable to read.

A little later Sybil Joines tells us:

Now I shall have to start all over again, trumping up a world to catch her in! Only a moment ago, as it seems, I was hurrying down a familiar road. For all its spectral dogs and rabbits, it was, as near as I could make it, the way home. The girl was in my sights! And then my heart flared up white inside me, and road and ravine and crowding hills all blanched and raveled into filaments like the thread-thin hyphae of a fungus. The girl is gone. I am alone on a blank page.

The “white” that confronts Sybil Joines so implacably, we discover, is the white of the page on which she is composing the reality of the land of the dead as she speaks. Riddance, it turns out, is not simply (or even primarily) a gothic fantasy about communing with the dead but an allegory about writing, or, more precisely about language. Indeed, making a metaphorical connection between the human body and writing has been a preoccupation of Jackson’s in all of her work. (The Melancholy of Anatomy, she has said, was conceived as “a kind of body” to be “read.”) However, Riddance arguably works out the metafictional implications of this trope most abundantly. It is Sybil Joines’s belief that the presence of the dead is a manifestation of language — specifically human speech — but they are most sensitive to the silences and hesitations of stutterers, through which the dead might speak and into which the stutterer might be able to enter and encounter the dead (thus some students actually disappear into their own mouths).

Many of the students at the Joines Vocational School also produce “mouth objects,” ectoplasmic emanations in various shapes that are then intensively studied for their possible meaning. An illustrated collection of these objects is offered in the book’s appendices where, lined up side-by-side, they look conspicuously like letters in an alphabet. To be alive, it would seem, means having access to language, and thus the ghostly presences of the dead make themselves known not through apparitions but through the palpable medium of language. If Riddance is truly a book about the paranormal (“necrophysics,” as Sybil Joines would have it), we could say it implicitly portrays the way language is haunted by its own ghostly origins and the now-spectral uses to which it has been put in the past. The same is true, of course, of literature itself, which continues to embody a living force only after the writer’s reckoning with all of the dead forms it has assumed in the past.

However much Jackson has experimented with hypertext and other unorthodox media, both Half Life and now Riddance show that her work is firmly situated in established literary history — perhaps we could say it, too, emerges from the silences and gaps lurking in that history.

Daniel Green is a literary critic whose essays and reviews have appeared in a variety of publications, both online and in print. His new book, Beyond the Blurb, has just been published by Cow Eye Press and his website can be found at: http://noggs.typepad.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.