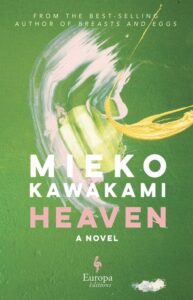

[Europa Editions; 2021]

Trans. from the Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd

Do you remember what it felt like to be a 14-year-old girl? While reading Mieko Kawakami’s latest novel Heaven, I found myself going back to this question and being reminded of the misery of being young and overlooked. I was a deeply introverted and painfully quiet young woman who grew into an awkward adolescent beset with self-doubt. At school I was friendless, timid, and ignored for being below the average height, and at home I was taken for granted for being good at academics and for being a girl. These situations rendered me utterly alone while also lending me a wild imagination.

Heaven opens with a note passed from one such lonely adolescent to another. It reads: “we should be friends.” At first, the 14-year-old narrator and recipient of this note believes it’s a prank by his classmates who bully him. They call him “Eyes” for his lazy eye. But he realizes that the message is from Kojima (nicknamed Hazmat), the “smelly, dirty girl” the other kids tyrannize. In that realization, something shifts, and the two outcasts forge a secret friendship.

Heaven is written from a place of knowledge and deep empathy for the ruthlessness of adolescence. Born and brought up in Osaka, Japan, Kawakami’s childhood was, in her own words, “hellish.” She eventually turned to writing and gained prominence in Japan for being a blogger. At its peak, Kawakami’s blog received more than 200,000 hits daily. In 2007, Kawakami won the Tsubouchi Shoyo Prize for Young Emerging Writers for My Ego Ratio, My Teeth, and the World. In 2008, she won the Akutagawa Prize for what was then a novella, Breasts and Eggs. Since then, she has dabbled in all forms of writing — novels, short stories, essays, and poems — and has risen to international literary acclaim.

In 2008, she wrote Heaven (titled Hevun in Japanese), her first full-length novel. In an interview, Kawakami said, “I try to write from the child’s perspective — how they see the world. Coming to the realization you’re alive is such a shock. One day, we’re thrown into life without warning.” This is reflective in Heaven, as it illuminates the loneliness of being a teenager. In Sam Bett and David Boyd’s seamless translation, Heaven is an unflinching, nervy, and painful portrait of adolescent misery. Those times when the afternoons were but a long stretch of endless void. Through Kawakami’s unsentimental writing, we see Kojima and the narrator’s intermittent friendship where they secretly create a safe space for each other. Kawakami is intuitive in her understanding of these 14-year-olds, innate in her grasp of how at any age a thinking person can go from feeling immensely self-satisfied to feeling deeply anguished in a matter of a few seconds.

Through the narrator’s unemotional descriptions of his daily torments, Kawakami sketches a portrait of a weak, diffident kid. Back slaps, taunts and casual cruelty aggravate to force-feedings of chalk, prolonged confinements in closets and other harrowing physical blows. There is emphasis on how the narrator’s and Kojima’s bullies are nameless, faceless perpetrators of violence. They torture, spout venom, and physically trouble their classmates and yet no one seems to be able to see them or find the marks they leave behind. The 14-year-old’s acceptance of this recurring violence is bleak, but his helplessness is challenged by Kojima who extends a fierce counter-perspective to the narrator’s passive resignation.

She insists that the narrator’s lazy eye is representative of his truest self. As she herself continues to lose weight, Kojima attributes it to getting closer to her “true self.” In a childish cadence she assumes that it is, in fact, their physical attributes that are the cause of their suffering. She philosophizes: “we’ll understand some things while we’re alive, and some after we die . . . What matters is that all the pain and sadness have meaning.”

While the narrator lives with his largely absent father, and his stepmother, Kojima has a rich stepdad. The details about their families lay the groundwork for revealing who these teenagers are, and how they become who they are. As they wrestle with the pain and isolation of their seemingly inescapable situations, circumstances lead them to each other. In each other’s company they parse for respite, a personal heaven if you might, that will make all this suffering worthwhile.

Kojima ardently believes that getting bullied is a “sign” of something good awaiting them, and sees herself and the narrator as designated empaths, even though Kawakami makes it clear that Kojima’s beliefs are irrational, even risky. Her beliefs might be a coping mechanism, but they are dangerous, and she doesn’t know that. The 14-year-old trusts that suffering enables her friend and her, in some way, to “know exactly what it means to hurt somebody else.” According to her, this makes them understand pain better than most others around. In a more sentimental writer’s hands, Kojima, in her intense faith, could come across as possessed, but Kawakami’s rendering makes the readers empathetic towards her. Heaven is high in morbidity around the bullying, yet comes suffused with compassion towards the aching, bruising teenagers. In that, it manages to push beyond what meets the eye. It prods the reader by depicting graphic scenes of bullying, while simultaneously pulling them into the layered analysis of social structures, gender equality and the roles people play, albeit unwillingly, within them.

With its crisp contoured sections on physical violence and the philosophy behind it, Heaven is not a breezy read. At times I had to keep the book away for more than a day to recover from a section. Kawakami elevates the book from being a mere modern day fictional tale about teenagers to a psychological study of the drama behind childhood bullying. She aches for the teenagers who go through the first few years of their lives questioning the existence of goodness. Even as Kawakami employs intense description for torturous moments such as physical violence, she also takes ample care to write in a way that readers come out bearing the emotional and psychological scars of the narrator and Kojima.

*

Another departure in Heaven is the refusal to acknowledge death as the final act of human life. According to Kawakami, birth is the climax of all those living. In Heaven even as the narrator and Kojima move through life with an irredeemable innocence and hope, they know that all is not conquered. Even though the narrator has found a friend to accompany him in his misery, he says, “I never lost sight of the possibility that this might be a trap.” This jolts readers, introducing them to a contradiction to which Kawakami will keep returning: how to trust the good in a world so cruel and filled with abject misery?

This is Kawakami’s way of grounding the existence of hopelessness in the lives of these adolescents. In doing this, she erases any hope for such people and lets them know that there will probably never be a happy ending. A silver lining, yes, but never that perfect, well-rounded closure. “In Japan, every year, many children take their own lives on the last day of summer vacation. Whether the adults knew what was happening to them or not, in the end we cannot change the children’s reality that made them make such a choice,” she said in an interview.

After the narrator and Kojima find each other, I couldn’t help but be taken in by the familiar turns of a freshly formed friendship. Their secret joys, clandestine meetings and wordy exchanges filled me with hope as I looked for even a faint glimmer of redemption. But Kawakami doesn’t relent. In revealing the painful experiences of bullying, and of being misunderstood she also shows that while these might be rite-of-passage events for most teenagers at a certain age, they remain inherently life-altering experiences. She pulls the readers in, portraying the loneliness of a teenager at 14, trying to figure out why he is being bullied. In doing so, Kawakami simultaneously invites us into the narrative while also locking us out.

*

During their secret meetings, Kojima talks in philosophical monologues. Ruminating on things like God, suffering, what differentiates humans from objects, Kojima comes across as an intense, complicated young woman. She says, “We’ll understand some things while we’re alive, and some after we die . . . What matters is that all the pain and sadness have meaning.” According to her, “Heaven” is a painting inside a museum of two lovers eating cake. “The more you look at pictures, not just of Heaven, but of anything, the more the real thing starts looking fake,” she says. Here, the novel suggests there is never just one reality. Not only does every person have their own version of what’s real, but the entire perception and definition of it is constantly shifting, a theme that continues for the remainder of the novel. In contrast, the narrator in Heaven is flat, almost unidimensional. We see him enthralled by Kojima, unable to fathom neither her, nor his tormentors. Chapter after chapter, we wait for the novel to open up before us from the narrator’s perspective, but he plummets into depression as an after-effect of the violent bullying at school. All this while, the book brims with Kojima’s notions, moods, perspectives.

In the end, Kawakami’s Heaven morphs into a clutch of questions that have been lingering at the back of the narrator’s mind since the beginning. The past and the future merge at the end, blocking the future as Kawakami presses the readers into the present. Then, it all boils down to the reader: some might see in it a kind of hopefulness, some might sense a smidgen of despair while others might feel absolutely nothing shift.

Kawakami’s enduring appeal lies in the fact that she is much more than Japan’s bestselling feminist author. She is a literary master whose prose shines with the inherently complex lives of women (Breast and Eggs) and children (Heaven). Through her writing, she delicately balances philosophy, invisible societal dilemmas, and the perils of modern life. Building on her existing oeuvre, Heaven has furthered her position as an unmissable voice in contemporary literature.

Anandi Mishra is an essayist and critic. She has worked as a reporter for The Times of India and The Hindu. One of her essays has been translated to Italian and published in the Internazionale magazine. Her essays and reviews have appeared in Public Books, Los Angeles Review of Books, Virginia Quarterly Review, Popula, Electric Literature, The Brooklyn Rail, Al Jazeera, among others. She tweets at @anandi010.

This post may contain affiliate links.