I went to my first AWP in Seattle in 2023, anxious and green. I’m an academic; conferences stress me out. The AWP was my foray into the world of creative writing and nothing like what I knew. It’s possible that writers don’t know how to have superficial conversations, or maybe they just don’t want to waste their time, but I knew straight away that I found my people, even if they didn’t know it yet.

With my rose-colored glasses on, I challenged myself (and an MFA friend) to go to one of the free AWP-sponsored breakfasts and found a table with five men and two empty seats. We asked if we could join. They were gracious and brought us into the conversation with ease.

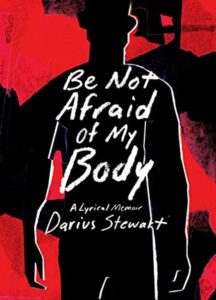

Darius Stewart was one of these men, an English PhD student at the University of Iowa. We learned that his debut lyrical memoir, Be Not Afraid of My Body, was forthcoming with Belt Publishers. He pulled out his phone to show us the cover images he received from his editor; he was trying to decide which one was the best fit for his book.

Be Not Afraid of My Body was the first book I ever pre-ordered. When it was delivered in February 2024, I ate it up. In six parts, Darius writes in gorgeous prose about his experience growing up as a closeted Black boy in Tennessee, his transition into young adulthood where he claimed his sexuality, all the while negotiating addiction and HIV. Darius’s essays are honest, clever, and fail to give any straight answers, in the best possible ways. We had a chance to talk on Zoom for this interview.

Annie Bartos: When I met you at the AWP in Seattle in 2023, we discussed a few versions of the artwork for the cover of your book. Are you happy with the end result?

Darius Stewart: I do like the cover. I like that I was able to have the kind of input I did. It started with a predominant image: a person or a body. I sent the designer several examples of the covers that I liked, and they all featured some kind of body. He sent me a few options and one was like a Disney World scheme, or Easter. Although, Easter might not be such a terrible analogy, considering my book carries themes of resurrection and things of that nature. But I don’t want to be compared to Christ, either, you know!

Well, that leads me to ask, who do you think is the primary audience for this book?

I would have thought the audience were folks like me—specifically, Black, gay, Southern men who are HIV-positive. But the book could be for anyone in a marginalized circumstance because it’s about the physical body and how it can be ravaged by illness, dependency, substance misuse, and all that. There’s a lot in the book about being a racialized subject that I think is important, and for the most part, I haven’t heard people discuss a lot (e.g., queer, Black, HIV-positive men). But the easy thing to say is that it’s for anyone who can appreciate what I’m writing—that’s who I am writing this for.

While the majority of the essays are written in first-person, there are a few places where you switch to second-person point of view. In fact, you begin the book with the essay, “Get Ghost,” which is one of the few second-person point of view essays.

Using the second-person in “Get Ghost” was so deliberate because I was setting up the foundational narrative design; I’m teaching the reader how to read my book. I started with the second-person point of view because I’m asking the reader to imagine. I wanted the reader to imagine being a young Black boy in Knoxville, Tennessee, you know, and keep going. I think by asking the reader to imagine elicits some sort of empathy.

By the time I get to the essay “Dearest Darky,” the second-person point of view is different. I felt the first-person POV would have been too close. There needed to be some distance. I was going to try third-person POV, but the second-person just felt like it was right. I wanted to the put the reader in the narrator’s shoes. I wanted some kind of discomfort to happen.

In “Dearest Darky,” I’m also taking responsibility for the harm I’ve inflicted on others. I’m holding myself accountable for some of the things I’ve done. There’s a kind of dramatic irony. I wanted my experience to be familiar in the sense that, you know, we’ve all kind of had our grievances to bear and broadcast, but sometimes we don’t take responsibility for those grievances. People like to bitch about things, but they won’t ever say what they did. I kind of wanted to call myself out, and also have the reader consider their own culpability in their own mistakes.

We both grew up in the 1980s when there was so much misinformation or non-information about HIV/AIDS. You capture the fear and confusion of a young person of our generation so well in the book. And yet, the virus still had a way of causing confusion even in your own adult life, which you captured in your essay about online dating while “undetectable and untransmittable.” Can you talk to us about this wider social lens on HIV/AIDS? How does the legacy of 1980s misinformation on HIV/AIDS affect you?

I would not have been doing due diligence if I did not include my own fear and confusion about the virus. I often think about how different my life would have been if I was a little bit older. I’m a sex positive person now, but I wasn’t in the 1980s. If I was, I probably wouldn’t be alive today, and that’s chilling. I didn’t write about this specifically, but readers might have gathered some sense of this, reading between the lines, because it really is such a powerful notion that anyone’s life can be so different than how it turned out: had I been sex positive a decade earlier, I wouldn’t be here.

I had to write about the first time I had knowingly come into contact with someone who was HIV-positive, and it freaked me out. I’ve never forgotten that moment. It’s ironic now that I was so fearful, how I stigmatized that individual. And then when I ended up realizing I’m HIV-positive, I was begging people not to be afraid of my body.

Stigmatization still exists, especially for Black and other people of color who are HIV-positive. It’s sickening. Some of the things I wrote in “Skin Hunger,” the quotes from people on my dating profile, those were actual comments that I curated. They were saying awful stuff and even their grammar was awful! I read these comments and knew they were white guys, and it was obvious that I was a Black man. The whole thread was racialized. And even though I write about not wanting to be romantically linked to white men, the narrator (of course) meets a white guy that he works with and everything goes out the window!

I’m curious about the white gay men in the book—how they’re both present and not present. The first essay of the book, “Get Ghost,” is about an older white man, who, we assume, is gay, and we assume, is cruising looking for a young boy toy. And then the book’s final essay, “Skin Hunger,” concludes with the narrator pining over a white boy called Lucas, who might or might not be gay. I thought that was really interesting to bookend the collection with these two white male characters.

Thank you for recognizing that. When I was planning the book, “I wanted to take the whole night to bed with me” just felt like the perfect way to end it. But leading up to that is a negotiation. The narrator has feelings for this white guy, and having the context of other white guys in the book, it just felt like a nice kind of tension, like there’s no closure, allowing for an open-ended ending. It’s like, in the beginning I want the white guy to go away, and then in the end, I’m like, Oh wait, come back. And not just come back, but come back so we can figure out what all of this means. It’s like I wanted to bring attention to binaries and how to negotiate two sides of the same coin. Like, I can be a body that is sober and addicted, or a body that is HIV-negative one moment and HIV-positive the next. But there’s really not that much distinction between those two types of bodies. There’s always a kind of tug-of-war happening.

I really appreciate the many tugs-of-war present in the book, especially with the parents. The father has a really different power than the mother, and the narrator manages being tugged by both of them. Then there’s the mother saying, “You don’t have to like it,” in the essay with the same name, when you told her you were HIV-positive—here’s another tug between you and her and between health and disease. What did this essay, and this quote from your mom, mean to you?

That was one of those indelible memories, like the first time I ever encountered an HIV-positive individual. My mom doesn’t remember saying what she said, but at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter what she said, it’s what I took from it. That’s what’s important as a writer. It’s like the facts don’t matter, but the truth does. Her saying “You don’t have to like it” allowed me to really examine how I felt in that moment and how she must have felt to have responded the way that she did. I did due diligence in the book by really trying to understand these complexities. You know, if I would have written that essay without trying to understand why my mother said that, I think that would’ve been terrible. I wouldn’t have been using the container of the essay to interrogate what this moment meant beyond the moment. Sure, it hurt my feelings. But she was feeling hurt, too. That’s why she said it.

The dialogue and the moment between my mom and me emphasized the theme of caregiving in the book. How we attend to our own bodies, and how we want others to attend to them as well. Writing about my mom, particularly when it had to do with my illness, was a perfect way to do all that. I wanted her to know that I was taking care of myself—that I tested for HIV and that I was negative. But instead of being happy about that, she became distraught. Because she always knew there was a potential for infection. And then, of course, you know, when I do end up HIV-positive, I had to revisit that moment again with my mom. I had to go back and investigate what that moment meant for our relationship and the ways we take care of each other and ourselves.

In some ways, Essex Hemphill also seems relevant to the theme of caregiving in the book. You incorporated his prose in epigraphs throughout the book. He is clearly an important person to you.

I guess this goes back to your earlier question about audience. Essex Hemphill was a Black, gay, HIV-positive writer who was very important to me when I was kind of coming to terms with my own sexuality in my late teens, early twenties. I don’t know how I would have been able to negotiate the kind of strife I dealt with without Hemphill. He represented the kind of heroism it takes to be open, unapologetically honest. He was sex positive and also an activist who was trying to represent an otherwise silenced community. His writing was coming out of the 1980s HIV/AIDS epidemic narratives that essentially whitewashed the problem and privileged the lives of white gay men who were dying of AIDS. Those narratives also infiltrated the publishing industry at the time: the only book-length narratives by a single author to have been HIV-positive, and probably later died of AIDS, were written by white, gay men. You could only find writers like Essex Hemphill in anthologies, or if you were lucky like he was, in his own single-authored book of poetry and prose. Finding him was important to me.

And because he was so important to me, I wanted to bring Essex Hemphill in more structurally to the book. My editor and I, or maybe I should give my editor all the credit, came up with the idea of having an epigraph for each of the sections, and those Essex Hemphill epigraphs were able to contextualize my own experiences.

Structuring the book around Hemphill really contributed to my idea of the book as a lyric memoir. A lyric structure gives the book meaning through juxtaposition. Each of these sections were a way to bring in his influence and also to indicate the kind of project I wanted this book to take on, which is similar to the project Essex Hemphill had—a kind of activist poetics. I didn’t want to further marginalize Black gay bodies.

How did you and your editor decide to use two epigraphs that weren’t Essex Hemphill? An essay early in the collection called “Etymologies” includes an epigraph by Giamattista Vico. And the final essay in the collection, “Skin Hunger,” begins with an epigraph by Walt Whitman.

That’s a really good question because the way those epigraphs originated were different. For “Etymologies,” I needed an approach to explain what this essay was trying to do, because you know, it’s not a conventional essay. I’m using etymology—words within the context of frames—but through a spelling bee as a kind of coming-of-age story. I needed to foreground this idea in the essay in a way that would help the essay make more sense. So, I found the Vico epigraph. It says that the universal principle of etymology in all languages is the notion that the order of ideas must follow the order of things. I like that idea of order, of ideas. For instance, if I am a sexually ambiguous preteen who is presumed to be homosexual because of how my body moves through the world in a way that doesn’t subscribe to social constructions of gender, I wanted to play with that idea, and especially how bodies order themselves around ideas, and ideas around order.

“Skin Hunger” was initially called “Be Not Afraid of My Body,” which took its title from a quote by Walt Whitman—incidentally, someone who Essex Hemphill pays homage to as well. When I started studying at the University of Iowa, I took a course on Walt Whitman. I was really taken by the nineteenth century idea of a “democratizing body,” that every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you. I’ve always been fascinated by that because it doesn’t really work in the context of HIV and AIDS. I wondered what happens when you’re too freely giving of your body? I wrote a whole essay on that topic for the Whitman class. It had three sections and each section had four interlaced Whitman poems. The epigraph I included in “Skin Hunger” was certainly one of those that stuck out for me from that original essay.

You have two MFAs—one in poetry and one in creative nonfiction. And you’re currently working on a PhD in English. Can you tell us how these three degrees interact and influence your writing?

For practical reasons, hopefully they will parley potential job interviews into a really good job somewhere, or some kind of job. A PhD may help me be more marketable because I didn’t necessarily scrub the bottom of the barrel to find an institution to get these degrees.

I’ve also learned to be a particular type of writer. In my poetry MFA, I learned a lot about who I am as a writer. Getting the MFA in nonfiction made me realize that the first poem I ever wrote was actually an essay, but I didn’t know that at the time. And certainly, poetry has only enhanced the possibilities for what I can do with the essay and non-fiction.

During my time in the nonfiction writing program, we were constantly questioning what the essay was and what could it be. These questions court controversy, and particularly when it comes to “auto” writing—writing about the “self.” But I’m really interested in how “auto” implies a nonfictional writing about the self that challenges genre categories. For example, when you affix “auto” to fiction, or theory, or ethnography, you can create useful categories that help to describe a very particular form of writing. But some people believe those categories create chaos. For me, the bigger picture is that the essay just seems to be so much more expansive than what we may have thought it was.

Montaigne gave us our modern understanding of the essay, and he best described the form when he conceived of it as an “attempt”—which we can see in perhaps the “conventional” sense in the work of E.B. White or Orwell or Woolf, but the essay can be more thrilling and permissive, especially when adapted in book form by the likes of Margo Jefferson, Kiese Laymon, Brittany Means, or Justin Phillip Reed. I don’t necessarily need to think in terms of genre. I only need to know that however I go about the writing, it all just needs to cohere. It has to make sense. The poetry helps all of that sing. It helps me create the music. It does a whole lot of labor. But the essay itself gives me a kind of permission to take my ideas and construct them on the page in whatever way feels right for whatever I am working on. The poetry adds the music and rhythm.

I’m also acutely aware of knowing when certain words ought to be on the page because they are aesthetically more pleasing to the eye than others, which is something Mitchell Jackson has talked about and is a wonderful way to discuss craft in a way that should be addressed more often. That is precisely why I don’t capitalize “black.” I hate the capital B. It’s bulky. It’s not pleasing to the eye. It’s just—I can’t stand it. I don’t have a political reason for using lowercase, as some people want to assume. No. It has nothing to do with politics. It has everything to do with aesthetics. Capital B is just an ugly looking letter.

Annie Bartos is a writer and an academic. Her creative works can be found in Pleiades, The Offing, Bending Genres, and elsewhere. She’s seeking representation for her hybrid collection of essays. She lives near the Salish Sea. Find her at www.anniebartos.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.