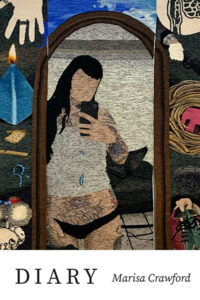

[Spuyten Duyvil; 2023]

Most of my life thus far has been spent trying so, so hard to be nice. And then, suddenly, a few years ago, I gave up on that as a guiding personality trait. Instead, I began looking for something else—a different way to be, a different way to move through the world. But the relinquishing of niceness is a difficult task, especially if you have been socialized into it forever. Learning how to be small took all of my girlhood, learning the opposite will take all of my adulthood. Sometimes though, I stumble across a text—art or theory or an Instagram post or a TikTok—that helps me find my way a little more. Marisa Crawford’s Diary is one of those texts for me.

Crawford’s third full-length collection of poems is alive with people and pop culture and feminist theory. There are sisters, and best friends, and men who you wish would go away, and bosses. There is work and sadness and boredom and clothes. There is so much love. In the opening poem, “Remember Me,” that preludes the rest of the collection, Crawford writes, “I’m six girls all at once / Sad store where we ate sad breakfast bagels / I once performed ‘Jenny from the Block’ karaoke, it sucked.” Each of these monostiches seems to get equal consideration and care on the page, held together by little strips of white space. Each a mini altar to a specific moment or feeling. Following the prelude, the rest of the poems, broken into three distinct, titled sections (SPRING IS HERE AGAIN, BIG BROWN BAG, and DIARY) echo each other with the intimacy and honesty of an actual diary. They reverberate with recurring names, images and objects: friends like Janie and Allison, a yellow SONY walkman, bloomies. In an untitled poem from the middle portion, Crawford writes:

I walk into the salad bar while the guy in front of me is

looking at the menu. He says, go ahead, and I say no,

go ahead, then he says, it’s not that big a deal, and I say

oh, fuck you. 40,000 women die of breast cancer each year

so my salad is in a bubble-gum pink container.

The exhausted lightness/levity of the oh, fuck you is immediately underwritten by the plastic violence of the 40,000 dead women. The pink salad bowl. These lines exemplify a kind of subtle, dark sharpness that threads its way throughout the collection. It is a self-awareness of an undertone of violence. A chronicling of the ways women are expected to move through the world and the chafing that occurs when we don’t behave, when we aren’t that nice. No one expects someone nice to say oh, fuck you, to the man who has offered his place in line, and that is why in 2024 I’m not so sure that niceness is serving us anymore. I don’t believe it ever really did.

Intricately and intimately interwoven into the discussion of being a woman in the world, are reflections on aging and the body. The poems both celebrate and disparage the speaker(s)’ body, nice tits, they say to themselves in the mirror before criticizing and critiquing. The speakers starve themselves, or think about times when they did starve themselves. They put on clothes that make them feel good, or they don’t. And we do these things, too, don’t we? We either love what’s in the mirror or we don’t. Perhaps that is ultimately what is so comforting about Crawford’s poems: while the speaker(s) are certainly scrutinizing themselves, that judgment is not directed outward to the reader. If you’ve hated and loved yourself, the poems seem to say, we’ve been there too. We understand.

Throughout the collection, the poems lope associatively into one another, weaving together song lyrics, lines from poetry, and always, references to 90s pop culture. The poems stay conversational and irreverent and smart, leading us through the streets of New York, and the aisles of fashion retail and drug stores. They feel like a day out with your friend, including the messy, sloppy parts where you tell each other how things are really going, how much you really hate your job, how not over your ex you are. In another untitled poem, Crawford writes:

In high school I’d try to go

the whole day without eating.

Then I tried being the cool girl

who doesn’t care about getting fat.

I had a stack of Seventeen magazines.

A quart of Phish Food ice cream.

Smear of vanilla

lipgloss where my mouth should be.

These lines, of course, are both sad and funny, but again, the predominant feeling I come away with is painful self-consciousness. The reflection of the speaker is both empathetic to the interior motivations of her previous self, but also closely, wryly, gives us the exterior as well. For the speaker, there is no separating the two: the body and what the body consumes become one entity with a smear of lipgloss. Crawford shows us the ways that girls and women try to be low-maintenance or “cool girls”—how they transform themselves over and over. Smears where our mouths used to be. For me, as someone in their thirties, this poem is both a look back into ways of being that I remember engaging in, and more often than I care to admit, I slip back into. What I mean is, these poems keep me company through my own awkward transformations: the girls I’ve tried to become, and the girls I have been.

I am certain already that Diary will be a collection I return to over and over again. Feminist theorist and writer Sara Ahmed writes about the need for a “feminist toolkit”—which is a way of talking about the items or ideas you carry with you in order to do the work you need to do in the world. After reading Crawford’s work, I am including her in my own personal feminist toolkit. A reminder that instead of being nice, I can be sad, and angry, and funny, and horny, and in and out of love, and rude, and smart. And that’s so much better, isn’t it? That is the kind of different I can really hold on to—the becoming I actually want to give my adulthood to.

Originally from upstate New York, Roseanna Alice Boswell currently haunts the Oklahoma prairies with her husband and their three cats. She is the author of Hiding in a Thimble from Haverthorn Press, and her chapbook, Imitating Light, was the winner of the Iron Horse Literary Review 2021 chapbook competition. Roseanna’s second full-length collection In the House | In the Woods is forthcoming with Cooper Dillon Books. She holds an MFA in poetry from Bowling Green State University and is a PhD candidate in English-Creative Writing at Oklahoma State University. Her work has appeared in: RHINO, The Missouri Review, THRUSH, and elsewhere.

This post may contain affiliate links.