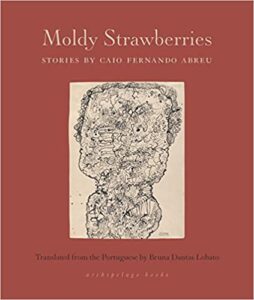

[Archipelago Books; 2022]

Tr. from the Portuguese by Bruna Dantas Lobato

In 1991, six years after the end of the military dictatorship in Brazil, one of the country’s most well-respected journalism programs, Roda Viva, welcomed Rachel de Queiroz as the evening’s guest. The 80-year-old had long established herself as an important name in Brazilian literature. Her debut novel, O quinze,which some originally refused to believe could have been written by a woman, had already entered the national literary canon as a significant example of the country’s modernist prose. To interview the writer, the show’s producers had invited several figures from the cultural scene at the time, amongst them was Caio Fernando Abreu.

That evening is remembered due to an infamous showdown between Queiroz and Abreu. In his very first question, the younger writer brings up politics, explaining his difficulty in dealing with what, to him, was paradoxical about Queiroz: a woman who was called a communist in the ‘30s for opposing Getúlio Vargas’s authoritarian government would align herself with the dictatorship in the ‘60s. Queiroz explains she had only supported the military government at the very beginning, before it had become clear the regime would not be transitional. Things become contentious between the two, however, when Abreu follows up by bluntly asking why the older author had been in favor of the military coup in 1964.

Queiroz’s political stance, although deserving of critique, must be understood within its historical context. The writer was part of a generation that lived through an authoritarian government itself and despised the figure of Getúlio Vargas. For Queiroz, who was a member of the elite, João Goulart — the president overthrown by the military — represented a return to Vargas-era politics. Nonetheless, as someone who was imprisoned by the militares, Abreu found Queiroz’s support of the coup incomprehensible. His feelings are clear throughout the evening as he takes sly jabs at the author’s opinions on several topics. The situation comes to a head at the very end when Abreu, in what has become the most well-remembered part of the interview, expresses his discomfort in having to honor a figure that supported the coup. After a tense, if brief, back-and-forth, the two end their interactions for the evening.

This episode comes to mind as I prepare to write about Abreu’s Moldy Strawberries, the first English translation of the writer’s 1982 magnum opus, set to be released in May by Archipelago Books, for two reasons. First, it is important to know to what generation Abreu belonged. Having been born in 1948, he came of age and wrote most of his work during the dictatorship. Second, seeing as he was a gay man who thematized homosexual relationships, it is fairly easy to predict that the question of sexuality will steer the way English speakers read Abreu’s literature.

The problem at hand, however, is that the homoerotic aspects of Abreu’s writings cannot be fully understood without taking into consideration the context of his stories. It cannot be ignored that the writer experienced the sexual liberation of the counterculture and the beginning of the AIDS epidemic under a deeply homophobic and violent authoritarian government. The Brazilian military dictatorship was a conservative regime that, amongst other things, served as a response to the social transformations in and outside of the country at that time. As such, Abreu was considered a danger to society by those in power not only for being gay but for daring to write about it.

All these issues are present in Moldy Strawberries. The book is composed of 18 stories, the first 17 divided into two parts, “Moldy” and “Strawberries,” while the 18th gives the book its title. Overall, the narratives are examples of their time. Deeply urban, they’re representative of a shift in Brazilian literature that would, in its contemporary production, choose metropolitan cities as its main stage. An existentialist dread runs throughout the narratives as they are marked by an exploration of the self, expressing the fears of a generation facing incredible challenges.

Amongst the most well-known stories are “Fat Tuesday,” “Sergeant Garcia,” and “Those Two.” The first one tells the story of two gay men who meet at a Carnaval party, a setting understood by the reader through the reference in the title. Fat Tuesday, which Americans may know best as Mardi Gras, is the day before Ash Wednesday and marks that last day of celebrations before Lent. Traditionally, Carnaval is meant to upend social mores. As Mikhail Bahktin’s study of the carnivalesque shows us, it is a time to subvert and go against dogmas hostile to change. It is, therefore, symbolic that Abreu sets one of his most violently homophobic stories during a Carnaval party. The violence does not occur only verbally in the form of some variation of “ai ai, look at them queens” thrown at the couple throughout the narrative, but also physically. At the beach, the two men are brutally beaten when they are caught having sex, and one of them ends up dead. The murder of a gay man during Carnaval sends a very clear message: in Brazilian society, with its deeply conservative and religious roots, some moral codes cannot be broken without punishment.

Similarly, “Sergeant Garcia” is the story of a young gay man who is seduced and loses his virginity to a sergeant. To readers today, especially those who do not know Brazilian history, the plot may seem cliché. The beginning, in specific, reads like the start of a gay pornographic movie. But to those aware of Brazilian history, Abreu’s attack on the military government is clear. In fact, I would say that the pornographic elements of the story may very well be integral to this attack. As such, those elements that seem cliché — the young, insecure gay man who is berated, and later seduced, by an older, masculine, dominant military figure — serve to ridicule those in power. This is a way of removing the militaryfrom its moral pedestal. Things take a darker turn when the sex scene is described similarly to a rape: “Burning, dagger, spike, sharpened spear. I tried to scream, but two hands covered my mouth,” the young narrator tells us, “He bit the nape of my neck. With a sudden jerk, I tried to throw him out of me.” The story, nevertheless, ends with the narrator feeling some sort of awakening to his true self. The ending, thus, serves as a reminder of the violent and unhealthy ways gay men are left to learn about their sexuality in a homophobic society.

As for “Those Two,” Abreu tells the story of a pair of male co-workers who form a close friendship. It is never confirmed if the two are involved in a romantic relationship, but its mere possibility results in their being fired. In that sense, Abreu shows the pressure men endure to perform a heteronormative idea of masculinity and how their actions are constantly patrolled. “Pale, they listened to phrases like ‘unusual and obtrusive relationship,’ ‘shameless aberration,’ ‘insalubrious behavior,’ ‘mental defect,'” the narrator tells us in the scene the protagonists are called in to be let go due to anonymous letters complaining of their relationship, “always signed by An Attentive Guardian of Morals.” The signature reminds the reader of the political context, showing how an authoritative regime does not exist apart from the population. That is, there are always citizens who are willing to watch over — and punish — people who do not fit their moral view of how the world should be. In this sense, they will support and reproduce whatever authoritative practices of the government that represents them.

Many of the other stories in Moldy Strawberries work in this key, touching both on the questions of homosexuality and the dictatorship. Consequently, they give insight into Brazil in the latter half of the 20th century. Caio Fernando Abreu is an undeniable gay icon in Brazilian culture. This was already true when the author was alive, but it was in the mid-1990s when he passed away from AIDS that this status was solidified. Since then, Brazil, in its never-ending paradoxes, has become a leading example of how nations should deal with the AIDS epidemic. That work, unfortunately, has been put at risk in the last few years due to the current administration (whose nostalgia for the dictatorship that Abreu fought against is well documented), as it has cut funds designated to the treatment and research of the disease. But 2022 is the year of federal elections in Brazil. As such, the 40-year anniversary of Abreu’s Moldy Strawberries may come with many things. Not only do we have the writer’s work published into English at the same time that scientists indicate a cure for AIDS may finally be on the horizon, but the most dangerous government for minorities in Brazil since the dictatorship may finally come to an end. There may not be a more symbolic way to celebrate Abreu.

Allysson Casais is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil.

This post may contain affiliate links.