The last nails are officially in the coffin, and we’re heaving it over the guardrail. Good riddance! we agree, as the nasty old box bounces end over end down the steep embankment. 2013 was a shitty year. Over the course of 12 miserable months, we lost countless friends, jobs, and celebrities. Temperatures reached record highs, while Congress reached record lows. News both domestic and international was a creeping tragedy, and forests were pulped to publish horrible books. In a word: yechh. In a few more: adios! do svidaniya! don’t let the door hit you on the way out!

Despite the past year being generally terrible, however, several very good books were published. We reviewed a lot of them in the course of our forced march through the malaise of 2013, but, as is unavoidable, we missed some. So this week the editors are running short reviews of good to excellent books we didn’t cover last year. Some weren’t written about because they were released late in the year, when our schedules were clogged and our lives bending toward holiday hangovers. Others were (self-)assigned but, mysteriously, never materialized. At any rate, we’re happy to run them now, as offerings to you, dear reader, as talismans to carry forward into 2014 and beyond.

* * *

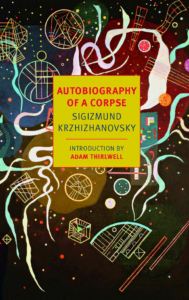

Autobiography of a Corpse by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky [NYRB Classics;2013]

Autobiography of a Corpse by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky [NYRB Classics;2013]

Soviet author Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky’s stories are so effusively strange that it seems a small miracle they ever made their way to publication at all. Admittedly, it was a long road. The Polish-Ukrainian transplant to Moscow wrote prose deemed too dangerously absurd to be published under Stalin in the 1920s and 30s, and his work wasn’t made publicly available until 1989 and the thaw of Soviet power. Autobiography of a Corpse, a collection of eleven short stories with interlinking themes, is the third work of Krzhizhanovsky’s to be published in English translation by New York Review Books, and it is one of the most confounding and rewarding books I encountered in 2013.

Krzhizhanovsky comes across as a kind of Bulgakov on drugs. He’s less cogent and precise than the great Soviet satirical surrealist, more feverish and unfocused, but the two were contemporaries, and their writings share a sense that the “real” of their time — the years of burgeoning Stalinist power — was unreliable. In Autobiography of a Corpse, a dreamed up toad lost on its way to death confronts his dreamer, a man falls into a chasm through the pupil of his lover only to find her previous lovers also lost in its depths, and a man who’s “goal in life” is to bite his own elbow becomes a hero for “sociopathic dreamers and fanatics searching in our realistic and sober century for the impossible and impracticable” and garners legions of “elbowist” followers (true to Soviet form there are many improbable “-ists” in this book). The world of these stories is one of extreme instability: everything dissolves into component parts, whether it is language or time or space or the self.

Krzhizhanovsky’s stories may be delivered in the form of deranged ramblings, but they are also clearly posed in conversation with the history of philosophy and with Krzhizhanovsky’s own literary contemporaries. Readers will want to make ample use of the notes at the back. But despite the citations, you do not need to be a Sovietophile philosopher to enjoy this collection. Autobiography of a Corpse is at moments laugh-out-loud funny, and the stories are overflowing with feeling. Krzhizhanovsky’s writing is marked by an exuberant and somewhat terrifying embrace of the inconsistency of the thing referred to as “I” and the simultaneous inability to see outside of it; in other words, the trap of always being only oneself. He defines society as “a kind of unit composed of solitudes,” lamenting, “to protect the life hidden between your temples from the life swirling about you, to muse down a street without seeing that street, is impossible.”

It is easy to see why that didn’t appeal to collectivist Soviet censors, and it is a particular kind of writer for whom the outside world is a hindering inconvenience to thought and experience. But “if a dreamer may not believe in the reality of his dream, then a dream may doubt the existence of its dreamer.” Keep that in mind, and pick up this book.

Helen Stuhr-Rommereim, Blog editor

This post may contain affiliate links.