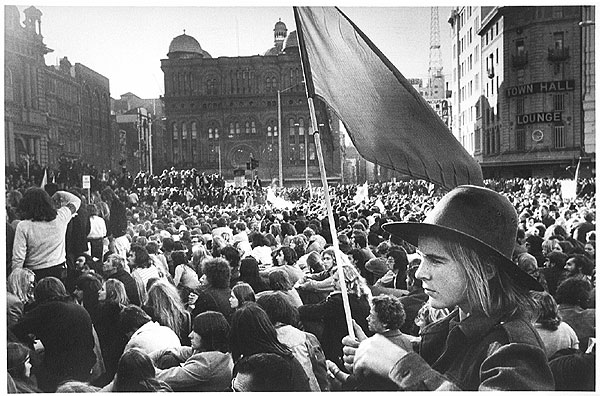

The Baby Boomers are the only Western generation in recent memory that can rightfully consider themselves revolutionaries. The cultural impact of the infant Tea Party and Occupy movements has (so far) been meager, particularly when compared to the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, the May 1968 protests in Paris, and omnivorous sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s (for the sake of convenience, we’ll consider the 1989 Velvet Revolution in Prague and the Solidarity movement in Poland as “Eastern” revolutions, i.e. taking place in former Eastern Bloc nations).

Growing up as the child of Boomers it was hard not to think of my parents’ generation as existing in an enchanted cinematic universe that mirrored the life stages depicted in the films American Graffiti, Easy Rider and ultimately The Big Chill. If not all the Boomers had been countercultural, many had at least grown up with a singular sense of their own impressiveness. Critics of the ‘60s generation have decried them as a spoiled, selfish lot, whose licentiousness led to an epidemic of divorce and Wall Street greed in the 1980s—the hippies, in other words, had traded in their idealism for fat capital gains and new, hotter spouses.

But revolutions, by definition, are messy undertakings that often spiral out-of-control (see: Robespierre) and invite counter-revolutionary backlash (see: Napoleon). If we consider 1968 as the apex of the Baby Boomer’s revolutionary spirit, 40 years later many people are still engaged in the shoving contest known as the culture wars over who was right, and more importantly, how we should live our lives.

Into this climate step two important writers, both of them Boomers, who have published books that directly (and indirectly) illuminate the current cultural wrangling in the West: Pulitzer-prize winning American writer Marilynne Robinson (b. 1943) who has a collection of essays called When I Was a Child I Read Books and the popular French philosopher and novelist Pascal Bruckner (b. 1948) has a new book called The Paradox of Love.

* * *

Marilynne Robinson may be the first American writer since Jonathan Edwards (technically a writer of sermons) to self-identify as a Calvinist. Robinson also describes herself as a Christian, a Congregationalist and an “unregenerate liberal.” She is too modest and Midwestern to add the moniker “one of America’s greatest writers,” but she is, and her fiction has opened up new and grand vistas in American literature. Her novel Gilead won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 2005 and it will prove to be a book that is read well-beyond our lifetime.

Despite Robinson’s generational affiliation, it is impossible to imagine the Idaho-born Robinson yucking it up with Ken Kesey and Allen Ginsberg at North Beach’s Caffé Trieste circa 1967. Robinson is far too circumspect, far too academic and scholarly; too much of an intellectual to have engaged in the frivolity and boorishness that often passed for serious thought in the counterculture. Robinson is not an radical in the received sense of the word, but a kind of Christian-humanist who operates in that most marginalized of milieus—the world of American letters.

Robinson’s book is, in part, a critique of Christian fundamentalism and neo-conservative thought—rekindled in the 1970s during the so-called “Fourth Great Awakening” of American religious fervor—which was, in part, a response to the sexual revolution.

Robinson takes up two broad themes in her essays, the first being a call for Americans to exchange a narrow, rigid view of human nature for a more expansive, cosmological one. “Our civilization has recently chosen to identify itself with a wildly oversimple model of human nature and behavior and then is stymied or infuriated by evidence that the model does not fit,” she writes. Her vision involves a divinely-inspired worldview that seems to have more to do with a Whitmanesque poetic consciousness than the Apostles’ Creed:

“In this universe of wonders and astonishments perhaps we should allow for the possibility that something remarkable occurred in the eons between the emergence of whatever life-form began the movement toward humanity and the realization of this tendency of humankind.”

Robinson is disturbed by a poverty of imagination and language that she finds in present-day America, and she believes that “lacking the terms of religion, essential things cannot be said.”

I can’t help but wonder if working at the heart of American programme fiction—Robinson is a permanent faculty member at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—while being a believing Christian, has left her feeling, if not philosophically isolated, at least somewhat misunderstood by students and colleagues. If one is to generalize about American writers of fiction, it’s probably a safe-bet that very few of them are self-declared Calvinists. And perhaps that’s why the essays contain a bit of Christian apologetics, as if she were rebutting colleagues bent on highlighting nothing but injustice and violence in the Judeo-Christian patrimony:

“Whenever I hear monotheism or religious difference singled out as the great cause of conflict among peoples, I wish some part of the population at some time in their lives had been required to read Herodotus and Thucydides . . . How peaceful was the polytheistic world, in fact?”

In the essay “Fate of Ideas: Moses,” Robinson reviews recent Biblical scholarship and criticizes scholars who seek “to primitivize and demean The Old Testament, encouraging the belief that it was full of ideas Western culture would well be rid of.” In the Mosaic Law she finds, not the underpinnings of injustice, but the seeds of western liberalism. “The law of Moses puts liberation theology to shame in its passionate loyalty to the poor,” she writes. “Why do we not know this?”

The second current in Robinson’s essays is the effort to distinguish her brand of Christianity from fundamentalism and conservative politics. In these critiques of the so-called religious right, I can’t help but think her sublime talents are wasted on such pedestrian work; she should leave such tasks to the many lesser writers who make a living off such polemics. Curiously, when Robinson does take political aim, she is strangely oblique, never really “naming names,” despite the obvious referents:

“In this climate of generalized fear social liberties have come under pressure, and those who try to defend them are seen as indifferent to threats to freedom . . . it is highly consistent with a new dominance of ideological thinking, and it is very highly consistent with the current passion for austerity, which gains from its status as both practical necessity and moral idea.”

At her best, Robinson is asking her fellow citizens—considering U.S. history and the realities of human nature—“What does it mean to be an American? And is it possible to attend church, to exist in a state of wonder—to revere the Bible—and still be an “unregenerate liberal?”

* * *

It’s hard to imagine philosopher, novelist and cultural critic Pascal Bruckner in any mood but a state of wonder, although his enthusiasms are more terrestrial and grounded in French society where religion has been passé for two hundred years.

Shifting from Robinson to Bruckner is a bit startling: it’s like listening to the works of Charles Ives right before attending a Phoenix concert in Paris. In contrast to Robinson’s intricate prose, Bruckner’s work is sparse and pared-down, and like many French intellectuals, he seeks to impress with his wit and originality: “The bourgeoisie and the whore used to have well-defined roles,” Bruckner writes. But in our present age “a streetwalker is often chic and austere, while soccer moms like to dress like whores.” With Bruckner, we are no longer in the cornfields of the American Midwest.

In The Paradox of Love Bruckner addresses the legacy of the idealistic, leftist 1960s straight on:

“The effort to wipe the slate clean has failed: neither marriage, the family, nor the demand for fidelity has disappeared. Bu the ambition to return to the status quo ante has also failed . . . Today the ideas of revolution and restoration are disappearing in favor of a complex, sedimented conception of a time that is neither a return to the past nor the advent of a new era . . . today, we are all, men and women, subjected to a contradictory requirement: to love passionately, and if possible to be loved, while at the same time remaining autonomous.”

In a post-1968 world where dating, sexuality and marriage are no longer governed by families, church or society in any meaningful way, men and women have to reinvent and negotiate what love is, and isn’t. In a world where procreation has been severed from sex, love-making has become an emotionally-charged form of high recreation: “Lovers have to give another pleasure,” Bruckner writes, “otherwise the amorous pair turns into a couple of plaintiffs. Woe to whoever botches the job!”

The separation of sexuality from baby-making and love from life-long commitment have led to some to conclude that marriage might be as relevant as fax machines. “In some Western European countries marriage has become pointless, because its avatars have been multiplied and the couple has ceased to be the canonical form of love,” Bruckner writes. “Our desire to take advantage of both states is so strong that the borderline between being married and being unmarried is becoming increasingly vague…The couple is gradually freeing itself from the three principles that were basic to the classical marriage: publicness, stability and solemnity.”

Controlling one’s own sexuality was key to the sexual revolution of the 1960s, and as a result, it shouldn’t surprise us that sexuality has becoming something of an idol, or in U.S. constitutional terms, the vehicle for our “pursuit of happiness.” Bruckner believes “sexuality has been assigned a new mission: to measure the married couple’s degree of felicity. Since the couple has retained only one of its formers roles, namely self-fulfillment, it inquires of eroticism, its new oracle, how it is doing.”

In a world where Robinson’s “universe of wonders” are mostly absent, our lovers must assume the impossible role of standing in for the transcendent, the divine. In some ways, we have all become like Madame Bovary, looking for the ethereal in the flesh of the lover. “The extravagance of our age consists in this unreasonable dream: everything in one: A single being asked to condense the totality of my aspirations,” Bruckner writes. “Who can fulfill such an expectation?”

If one is tempted to view Bruckner as a social conservative, think again. Despite the complications of contemporary love and marriage, Bruckner believes the current plurality of relationship is progress: “We can choose between traditional marriage, cohabitation, and a free relationship, that in the course of our lives we can encounter several forms of interpersonal connection is ultimately a major step forward.” Yet the very point of Bruckner’s book is to add some nuance to the progressive 1968 legacy, admit some mistakes, and also find a place at the table for tradition. Bruckner cops to an admiration for the “noble perseverance of the old couple,” and he believes there is a way to counter the diminution of the feeling of love that we experience in long-term relationships:

“By basing the relationship on bonds other than ecstasy and frenzy: on esteem, on complicity, on transmission, the joy of founding a family, the quest, of which the ancients speak, for a certain immortality through children and grandchildren. We have to rehabilitate the temperate climates of sentiment, oppose to made love the gentle love that works to build the world, comes to terms with the passing days, sees them as allies, not as enemies.”

* * *

When I was a teenager, I came across a quote by Robert Frost that had a great impact on me: “I never dared to be radical when young. For fear it would make me conservative when old.”

In today’s world it doesn’t matter if your personal life is in disarray, it only matters if your political views are in proper order, which is say they all fit neatly in a narrow, ideological box that meets with the approval of one’s like-minded Twitter followers. This is not the intellectual world that Bruckner or Robinson occupies, and maybe that’s what makes them the true revolutionaries—they don’t sound like me, or you, or anyone we know.

Robert Fay is California-based writer who recently completed a memoir. Visit his website at Robertfay.com or follow him on Twitter at @RobertFay1.

This post may contain affiliate links.