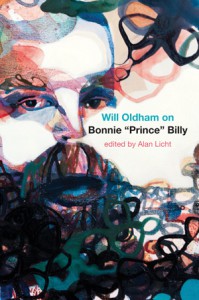

[W. W. Norton & Company; 2012]

Back in April a piece appeared on the New York Times Style Magazine blog announcing the imminent UK release of Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy, with a US edition to be published in the fall by Faber & Faber. For any longtime and slightly obsessive fan of Will Oldham — which is to say the majority of his fan base — this was something of a major event. We learned that “within the book’s 382 pages Oldham answers nearly every question one might wish to ask about his prolific output,” giving some credence to his characterization of the project as “the last interview.”

Despite a long, productive, and notably wide-ranging career in music and film, Oldham has always been a somewhat elusive figure for the media and for his fans. This is partially due to his provincial nature as a stalwart of the Louisville arts community, and partly due to an admirable disregard for the conventions of media presentation. Thus the lengthy interview, exhaustive and detail-oriented in the hands of musician and occasional Oldham collaborator Alan Licht, is less about setting the record straight than about providing the proper forum for a fuller picture of the artist and the man to emerge.

To my mind this is a more important enterprise than the slew of memoirs by high profile baby boomer musicians that have been released in the past few months, mainly because Oldham’s general lack of media availability can have certain effects on his fans. I remember my first trip to Louisville to visit my friend Lydelle, a very cool person I became fast friends with when we were teaching in France. However, she became infinitely cooler once she divulged that she ran in similar circles with “Will.” One night she took me out to see a local supergroup called The Health & Happiness Family Gospel Band. It was everything that I could have wanted as a Yankee in the South: faux-wood panels, very cheap beer, an opening group that was passing around moonshine made from an old family recipe, and then a sweaty man in a loosened tie flanked by a guitar player with a jewel-studded bolo leading a raucous gospel show. And then, just as Lydelle had threatened on the way there, Will Oldham showed up, first just to watch and catch up with friends, but later to join the band on stage for a few songs. This was too much for my shamelessly exoticizing gaze – to see one of my favorite artists in their native environment, awash in authenticity. As I drove past a decidedly inauthentic stretch of man made lakes in Indiana the next day I called my friends to make the — to my mind, at that point, brilliant — distinction between the vibrant cultural impulse of the South and its complete erasure once you crossed over into the Midwest.

Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy goes a long way to temper these over-the-top and naive (to be generous to my younger self) reactions to his musical and artistic output. One of the interesting things you learn about Will Oldham is that his ascension in the Louisville music world was first and foremost as a fan. While his brothers Paul and Ned were playing in bands with people like Steve Albini (Big Black, Shellac), David Grubbs (Gastr Del Sol), and Ben Chasney (Six Organs of Admittance), Will was pursuing acting with the Actors Theatre of Louisville. Though if he was just a music fan, he was really good at being a fan, forging friendships with the artists with whom he was to later collaborate and meeting some early heroes (like Glenn Danzig, a surprisingly influential early figure in Oldham’s musical life).

At the age of 19 Oldham had already assembled an impressive acting resume – landing roles in John Sayles’ Maetwan and working in productions associated with the Actors Theatre – but decided to abandon this path after an ill-fated stay in LA. Here is how he neatly sums up his decision:

“I went to Los Angeles, got the agent, went on numerous casting calls and numerous auditions, had numerous discussions with agents, did Everybody’s Baby and saw how people that I admired…were living and what the issues at hand were, and what life in Los Angeles was like, and what politics and processes most people were engaged in on a day to day basis…and just thought ‘I don’t recognize what is cool, I don’t recognize what I was hoping for.’ It started to seem like, ‘Wait, this actually has no relationship whatsoever to what I thought I was preparing for. Uh oh.’”

This kind of reasoning indicates a pattern for Oldham, and it’s one that readers are likely to find admirable. What is progressively revealed in the book is the whole way of life, not just the particular rationales that influenced key “career decisions.” So, for example, Oldham speaks of a breakthrough, a “new style of touring,” that came during a 2002 tour with rainYwood, who eventually turned into Brightblack Morning Light. What made it revelatory was the seemingly banal insight that the terrain you cover during a tour could become instantly more meaningful and fulfilling if you were doing it with friends and took time to enjoy the setting.

So they limited the tour to three western states and would camp out most nights after the show, often near surfing opportunities. Oldham’s frank accounting for why he often eschews conventional touring and publicity protocol reveals how difficult it is to remain centered over the course of a career when there is so much pressure pushing you towards uncomfortable situations.

The book is organized into 11 sections, more or less chronologically ordered, but often moving forward or looping back upon topics already covered. Though the focus here is on Oldham, Alan Licht deserves a great deal of credit for moving so deftly through the material, sometimes prompting his subject with an apt Nicholas Ray quotation, a reference to an old Robert Duval film, or a lyric from anywhere in the catalog. As the book proceeds he provides enough of an auto-commentary to keep the biographical thread during forays into topics that any fan would find interesting: “Do you find drugs useful, enjoyable, or both?” “How important are lyrics to you as a listener and as a singer?” “Have you had any interesting dreams lately?” “Overall, what effect do you think the audience has on your work?” These are interesting questions, and Oldham consistently provides considered, interesting answers (to tease the dream question a bit, I can say that it involved Bruce Springsteen, a haunted hotel, and an aborted attempt to call a phone sex line).

There is a potential for any extended statement from an artist to become tedious at a point if they are clearly going to remain truthful throughout. The will to self-mythologize is what makes books like Bob Dylan’s Chronicles or Errol Flynn’s My Wicked, Wicked Ways such a pleasure to read. Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy can get bogged down at times in the minutia of the recording process, or cataloging who played what parts on certain records and live shows. But Oldham’s life has led him in a sufficiently varied set of directions and put him in contact with enough interesting and creative people that you appreciate his attempt to set things down in a relatively straightforward manner.

Hearing how he imagines the character of Bonnie “Prince” Billy — arguably the guise under which he has solicited the most attention from fans and press alike, but initially a concession to his fans’ misguided insistence that all songs should have some kind of intentional creator behind them — in terms of his larger musical project is incredibly instructive not only for his listeners, but also for anyone who thinks deeply about the function of “the alter ego.” You also get sidelong glances at the early days of Drag City; brushes with seminal bands like The Royal Trux, the Silver Jews, and the Dirty Three; or encounters with Harmony Korine, who used to call Oldham using a fake name years before they met in person (Korine provides the “You Fuck” on “A King at Night” from Ease on Down the Road).

The most appropriate frame through which to view the book is no doubt as a reference for fans. Those not familiar with the work or with the lacuna surrounding Oldham’s identity as an artist and man will most likely get lost in the steady stream of unfamiliar names. However, as an antidote to the self-serving, grandiose, and often grotesque nature of many “rock memoirs” Will Oldham on Bonnie “Prince” Billy is a refreshing kind of book — one completely appropriate to the creative character with the modest and reasonable ambition of leading a creative life. Oldham can be effortlessly weird without giving the reader pause. That such an approach doesn’t mean that you can’t amass a large, devoted audience is a lesson that deserves a wider circulation and has found a worthy ambassador.

This post may contain affiliate links.