I only recently found out about Steven Millhauser. An acquaintance mentioned one of his older stories, “Cat and Mouse,” as being one of her all time favorites, and as serendipity would have it, Millhauser’s career-spanning collection, We Others, (which contains “Cat and Mouse” along with other older and new stories) had just been released. So, I started reading. Not surprisingly, I discovered that the stories are amazing.

I only recently found out about Steven Millhauser. An acquaintance mentioned one of his older stories, “Cat and Mouse,” as being one of her all time favorites, and as serendipity would have it, Millhauser’s career-spanning collection, We Others, (which contains “Cat and Mouse” along with other older and new stories) had just been released. So, I started reading. Not surprisingly, I discovered that the stories are amazing.

Wanting to know more about the man who could do such incredible things in his stories, whose every word was so meaningful and so well placed that reading him felt like some kind of telepathic access into a shared reality, I googled him. I started reading the many available interviews in which he is asked about his favorite authors, favorite stories, about what he’s reading lately, about what he thinks short stories ought to do, and, most interestingly, about his writing process. And here is the one thing that stuck with me. When asked by Columbia Magazine if his writing habits had changed over the years, he replied, “they’re the same as always, except that the final version is now on a computer instead of a typewriter. I write by hand, using a yellow hexagonal pencil, in a spiral-bound notebook.”

Then, there was Jennifer Egan. The New Yorker’s fiction blog asked her about her writing process and she replied, “well, I write fiction by hand generally.” This was beginning to be too much to ignore. If these two great writers are doing it this way, then maybe there’s something all of us word-processing folks are missing.

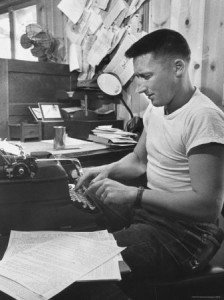

Like everyone else, I’ve seen the photos of Faulkner and Hemingway sitting at their typewriters. And I understand, although maybe in an abstract way, that technology affects the writing process. But it’s hard for me to see the difference because, my personal 4th grade journal aside, I’ve never done much writing outside of a computer screen.

Up until reading these interviews, I’d never thought about it. The computer is my writing tool and using it to write feels just as natural as using a cup to drink from — it is so obvious and natural that I’d never stopped to think about it.

For people who have been writing since before the existence of the internet and complex word-processing software, writing by hand seems normal, natural. But it’s just the opposite for many of today’s young writers, who have always had instant access to note-taking applications and fully featured word-processing on their computers at home and on the iPhones that are in their pockets.

How you write highlights what I think the writing process is about — ritual, habit, focus and familiarity, about the process being so fluid and unobtrusive that it serves as a catalyst rather than an obstacle, and, more than anything, about caring enough about what you’re writing to keep going even if the circumstances aren’t ideal. To me, the biggest difference between writing by hand and typing into a word processor is just a matter of habit and comfort. But of course, there is the issue of the internet.

Wells Tower (who I love so, so much) has said that the internet is “toxic to the kind of concentration fiction writing requires. It’s difficult to write good sentences and simultaneously buy shoes.” Nobody is arguing that good writing doesn’t come from thoughtful concentration. But it’s just as easy to disconnect a computer/writing device from the internet as it is to potentially become distracted while writing by hand on a notepad. It may even be possible that the close proximity of Internet distractions available on computers forces an even higher level of focus and concentration for determined writers. But what’s more interesting than the debate over writing methods is this fixation on how writing gets done, as if it were some type of magic.

That so many writers are asked this question by interviewers, that there’s such a fetishisation of the writing process, is more than a little unsettling. The question suggests that if only the process could be duplicated, so could the results. What a mechanistic, depressing way to view the artistic process. The notion that the minutiae of the writing process (rather than the thinking, experience, influences, and the effects of the writing itself) are especially important also explains why academia privileges writers whose works are few and far between (and who constantly moan and wail about how hard and slow the process is — I’m looking at you, Junot Diaz) while completely overlooking someone like Donald Goines, who wrote no fewer than sixteen great novels within a five year span, some while imprisoned, yet has received almost no critical scholarship.

King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail was composed in the margins of a newspaper. Can you tell which parts of this post were written on a phone? And would it matter if you could?

This post may contain affiliate links.