Dime Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell, by Charles Simic

Dime Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell, by Charles Simic

[NYRB Paperback, 2011]

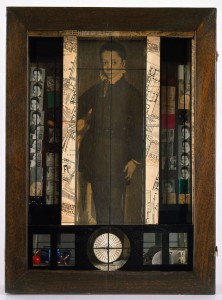

Dime Store Alchemy is an ingenious little book of prose poems by the American poet Charles Simic about the life and work of Joseph Cornell. A maverick Surrealist working in mid-century New York, Cornell is best known for his collage boxes, miniature cabinets of curiosity filled with found objects like old maps, cut-outs of ballet dancers, tiny stoppered bottles full of marbles, rocks and sand, compasses, drawers and color etchings of birds. Dime Store Alchemy’s hybrid structure and voice—bridging autobiography, biography, memoir, the critical essay and poetry—mimics Cornell’s boxes, compact yet expansive and enchantingly allusive. Collage is both the subject and the modus operandi of Simic’s book, which argues that “the collage technique, that art of reassembling fragments of preexisting images in such a way as to form a new image, is the most important innovation in the art of this century.”

Simic also shows the personal significance collage held for Cornell, for whom Manhattan junk shops were as full of spectacle, discovery and thrill as the city itself. The found object was a window through which he could escape into another world; he described “an abstract feeling of geography and voyaging I have thought about before getting into objects” (Cornell’s own words—one of the charms of Dime Store Alchemy is its inclusion of free-standing passages from the artist’s journals). Here’s how Cornell described the hundreds of files of notes and pictures he culled to make his art: “a diary journal repository laboratory, picture gallery, museum, sanctuary, observatory, key… the core of a labyrinth, a clearinghouse for dreams and visions… childhood regained.”

Dime Store Alchemy is full of these kinds of freewheeling connections. Simic brings together Cornell’s Christian Scientism and his sympathy with the American Romanticism of Whitman, Emerson and Thoreau, his New York milieu and his Paris imaginary, his affinity for Emily Dickinson and Houdini; he shares quotations from and anecdotes about Poe, Melville, Nerval, Thoreau, Breton and de Chirico. Poems like “Old Postcard of 42nd Street at Night,” which begins, “I’m looking for the mechanical chess player with a red turban. I hear Pythagorus is there queuing up, and Monsieur Pascal, who hears the silence inside God’s ear,” are curious dreamscapes, linguistic counterparts to the strange, silent theaters of Cornell’s boxes. “I have a dream in which Joseph Cornell and I pass each other on the street,” the book begins. “This is not beyond the realm of possibility. I walked the same New York neighborhoods as he did between 1958 and 1970.” That missed connection suggests the impetus for this collage of a book, which is more personal, eclectic and multiplex than mere homage; it creates an imaginary meeting place for two American masters.

—Amanda Shubert, Features Editor

“Spem in Alium” by Thomas Tallis

DJ Spooky by way of Frank Gehry by way of Goethe by way of God stated that music is liquid architecture and architecture is frozen music.

It works as quite an evocative description in either direction, and I’m quite partial to it, but there is only one Work of Art that I have ever encountered that truly lives up to the possibilities of that claim, and that is “Spem in Alium” by Thomas Tallis.

Thomas Tallis was a composer and church musician in 16th century Tudor England. He looks rather dashing with his quill pen and ruffled sleeves but according to Wikipedia there are no actual surviving portraits of him painted while he was still living. So that might not be what he looked like at all. I find this to be rather fitting for someone who composed the most beautiful piece of music/construction of space ever created.

Written for 8 choirs of 5 voices each (that’s 40 distinct parts!), “Spem in Alium” begins as a spindling out of one pure clear voice, which gradually gathers and weaves a veritable ocean of sound. Parts rise and fall out of the murmuring mass (and I love how you can often hear the quiet chatter beneath the melody) as the sound and space stretch and compress, fold over and divide, never settling on one shape.

Something like this.

It suggests the possibility for true individuality while at the same time promises a wholeness that can be achieved, that can emerge out of the interconnection between unique parts. But it is also a beauty that is terrifyingly stark, as in spires of churches that reach up to touch the sky like lightning rods, and wait, poised there, for something to strike down, at this time of year when (at least in Western NY) the sky is eternally gray. “Be mindful of our lowliness,” the final line of text reads.

I can imagine those 16th century English churchgoers shivering in the pews, feeling their smallness, finding God and finding God again. For me, the associations are more secular. Like flocking birds, like bacteria under microscopes, like humans viewed from afar with time-lapse, the music surges, crests, and, most importantly, envelops. Tallis intended that the piece would be performed with the 8 choirs surrounding an audience in a horseshoe shape, passing sound around, between, and over the listeners, but even on my lowly MacBook speakers, it is immersive. Brian Eno made music that could turn your home into an airport and Erik Satie wrote songs that could transform compressions of air into furniture, but Thomas Tallis composed something that, as it sublimates between walls of sound and architectures of liquid, turns my room into something profanely sacred, and allows me to achieve one of the only true instances of the sublime I have ever experienced in art.

—Jesse Miller, Reviews Editor

Grace Paley: Collected Shorts, directed by Lilly Rivlin and Margaret Murphy

Grace Paley: Collected Shorts, directed by Lilly Rivlin and Margaret Murphy

The Little Disturbances of Man, by Grace Paley (1959)

I was introduced to the short story writer Grace Paley through Lilly Rivlin’s excellent documentary Grace Paley: Collected Shorts. Paley grew up in the Bronx, the daughter of turn-of-the-century Jewish immigrants from Russia. In the film’s interviews she is a tiny old woman with a shock of white hair and a knitted cap, offering wry insights about love as she lights her kitchen stove. This made me want to be Grace Paley when I turned eighty. It also made me want to read her books. Grace Paley: Collected Shorts gives a good introduction to Paley’s long life (1922-2007), notably her impassioned political activism. But what emerges most clearly from the documentary is Paley’s distinctive voice, full of humor and conviction. It’s this voice that permeates and defines her stories.

Paley’s output was small compared to the authority of her voice: she published only three original collections of short stories along with a few collections of essays and poems. I took her slim first book of stories The Little Disturbances of Man (1959) with me on a recent bus ride, and it proved a perfect companion for the trip. Most of the stories are written in the first person. Paley’s narrators trumpet their existence from the first line and then hardly pause for breath. They are primarily women, young and old, who have grown up in crowded households in crowded city neighborhoods and who know how to speak up. They are inheritors of a well-worn oral tradition, interested in the how of telling their stories more than a shapely plot. The opening story of the collection, “Goodbye and Good Luck” concludes:

So now, darling Lillie, tell this story to your mama from your young mouth. She don’t listen to a word from me. She only screams, “I’ll faint, I’ll faint.” Tell her after all I’ll have a husband, which, as everybody knows, a woman should have at least one before the end of the story.

Paley’s stories are full of quirky phrasing striving for a truthful description of experience. What Paley accomplishes in this first collection are vivid lives told through or as digression. I look forward to reading more.

—Anna-Claire Stinebring, Reviews Editor

We Jam Econo: The story of The Minutemen

“Our band could be your life / real names be proof / me and Mike Watt, we played together for years/ punk rock changed our lives”

That’s the first verse of The Minutemen’s “History Lesson Part II,” the song that closes Tim Irwin’s superb documentary We Jam Econo. It’s fitting that the first line is also the source for the title of Michael Azzerad’s definitive book about the rise of American hardcore/punk/DIY music: the whole song serves as an introduction to everything that matters about The Minutemen and, by extension, punk rock. The best thing about We Jam Econo is that it does the same thing. It makes a case for one of the most original and important American rock bands with rare videos and interviews with figures such as Henry Rollins, Thurston Moore, and John Doe — while also using the band to explore the most important thing about punk: that it’s about going out and doing something you care about doing, and not giving a fuck about anything else. D. Boon, Mike Watt, and George Hurley (who is, I should add, one of rock’s greatest drummers) were just 3 guys from Pedro, but they went out and did it. We Jam Econo makes you want to go out and do whatever it is you’re passionate about. And the songs are great, too. To quote the last tweet of the late Heavy D, “BE INSPIRED!”

—Alex Shephard, Editor-in-Chief

Downton Abbey, created by Julian Fellowes

Downton Abbey is a British historical drama that follows the Earl of Grantham and his family, the aristocratic Crawleys, as well as their coterie of servants. The series begins with the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, and covers the course of WWI and the onset of Spanish Flu through the first and second seasons. But more than history, this show is about its characters.

While Downton Abbey is eventful, to say the least (and the second season ups the ante even further), despite its occasionally eyeroll-worthy storyline the show magically never loses sight of its characters. From Daisy, the crushingly earnest and simple-minded kitchen maid, to Mary Crawley, the spoiled and proud (yet disarmingly self-aware) eldest daughter of the Earl of Grantham — everyone in the series is a remarkably well-developed, complex character. And this attention to character not only redeems the show’s occasional absurd plot point: the honesty with which the writers’ treat their characters ropes even skeptical viewers like me in to the melodrama, completely and with no sense of irony. And I’m not alone: this past year, the show was entered into the Guinness Book of World Records as the most critically acclaimed television show of the year.

Watch Downton Abbey, Scene from Episode 1 on PBS. See more from MASTERPIECE.

If you’re intrigued: the first season of Downton Abbey is currently streaming on Netflix. The second season will begin airing on Masterpiece Theater on PBS on January 8, 2012.

—Nika Knight, Interviews Editor

Impossible Spaces by Sandro Perri

My friend introduced me to this album a few hours after I’d run my car into a ditch. The road was still icy after a freak October snowstorm took me, my car, and my helpless passengers off-guard and off-road. Still, everyone came through without a scratch. I settled back into the road and the early-morning light as “Impossible Spaces” looped, deconstructed and basically fell apart during its crescendoing tour of the cosmos. I thought about how lucky we were.

—Max Rivlin-Nadler, Blog Editor

This post may contain affiliate links.