By Michael Schapira

Age of Fracture by Daniel T. Rodgers, Harvard University Press, 2011, 352 p.

Age of Fracture by Daniel T. Rodgers, Harvard University Press, 2011, 352 p.

Unmaking the Public University by Christopher Newfield, Harvard University Press, 2011, 395 p.

As summer comes to a close Full Stop is offering you a valuable service – a shortcut to projecting significant advances in erudition and insight into the most pressing political issues of the day before rejoining colleagues, friends, and relatives in the fall. We are calling it “How to Master x in Two Weeks” (a title which offers further proof that we employ no paid advertising or PR consultants).

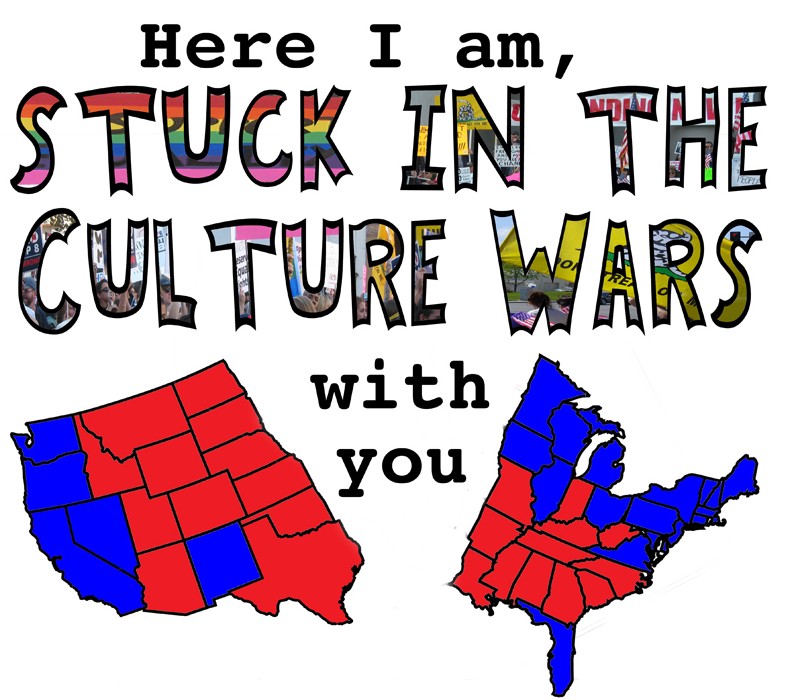

In this installment we focus on two recent publications from Harvard University Press – Age of Fracture by Daniel T. Rodgers and the paperback edition of Unmaking the Public University by Christopher Newfield – both of which effectively and engagingly ground increasingly incoherent debates about the debt, public education, and social services in the longue durée of the culture wars and their aftermath.

Each book relies on movements in intellectual history over the past 30 years, essentially following the books, articles, keywords, and legal battles that set the terms for public debate. This is both an asset and a deficit: it allows the authors to cover an impressive amount of ground (affirmative action, feminism, post-structuralism, the New Left and its more effective counterpart on the Right), but sacrifices a finer grained understanding of social upheavals. Rodgers, a distinguished professor of history at Princeton, is unapologetic about this approach, arguing that

what precipitates breaks and interruptions in social argument are not raw changes in social experience, which never translate automatically into mind. What matters are the processes by which the flux and tensions of experience are shaped into mental frames and pictures that, in the end, come to seem themselves natural and inevitable: ingrained in the very logic of things.

To this end Rodgers is essentially serving as a very perceptive witness of events as filtered through the concepts current amongst top intellectual historians at top universities – and he fulfills his office with great clarity and breadth of vision. Newfield, who is younger, teaches English at a state university (UC Santa Barbara), and is deeply engaged in the struggles he writes about (having worked against budget cuts to higher education with the UC Faculty Senate), tends to pepper his historical account with polemical arguments as to whether certain changes are beneficial or disastrous. While both authors unfold the steady creep of particular modes of economic thinking into most areas of our life, Newfield is more likely to show — through a tedious analysis of the UC budget process, for example — how this undoes public institutions and precipitates the “flux and tensions” that Rodgers deals with at a remove through landmark books like A Theory of Justice, Bowling Alone, or The Closing of the American Mind.

So what is the basic story that these books tell about the past 30 years (what Rodgers dubs the “age of fracture”)? Essentially, the forms of post-war consensus that underwrote American politics, social norms, research programs, economic organization, and cultural production broke down very quickly from the 1970s onward. Whereas many writers focus on moments of rupture in the 1960s (the civil rights movement, anti-war protests, feminism, unrest on campuses), Newfield and Rodgers are more interested in how, by whom, and for what reasons society was put back together. Both agree that the particular forms of these ruptures made reassembling the nation extremely difficult and contentious, as evidenced through the culture wars attending each attempt.

For Rodgers this difficulty stemmed from a broad shift in orientation, from a post-war period aiming for “strong readings of society” and consolidation to the past 30 years, in which “the dominant tendency of the age was towards disaggregation.” As he puts it, “The era began with Alex Haley’s sweeping historical account of kin and memory; it ended with race in question marks.” Moving deftly through the growing influence of market ideology (examining the University of Chicago’s Law and Economics movement and its broad social and political influence), the movement of power away from rigid and oppressive structures into the diffuse realm of culture, the multiple understandings of identity proliferated in contentious debates over race and gender, and the difficulty of articulating strong post-Cold War definitions of social mission, Rodgers paints a compelling picture of the era of disaggregation.

The difference between Rodgers’ “disaggregation” and Newfield’s “unmaking” is the latter’s desire to assign some blame for how things eventually shook out. Unmaking the Public University begins with an account of how public higher education (and particularly the UC system) was hands down one of the most effective social institutions at balancing inequalities in income, opportunity, and influence in post-war society. The trouble was that universities were too effective in fulfilling their mission, growing a culturally diverse middle class more assertive in challenging the traditional elite in the workplace and in the political sphere. Much of Unmaking tracks the counteraction of “culture warriors,” by whom he means “members of the conservative offensive against new academic and social forces…who had reasons to sever knowledge workers from the cultural conditions that gave them authority and prominence.” Through a brilliant piece of indirection “culture warriors did not openly attack the economic position of the middle class, but they did attack the university.” Here we can see how Newfield and Rodgers treat the content of the culture wars a little differently – Rodgers as the jockeying by political forces on the right and left to reconstitute a fragmented society (e.g. through the development of think tanks, media outlets, or campaign tactics), Newfield as a balder political battle initiated, successfully prosecuted, and ultimately won by the Right over a less organized and effective Left (the debt ceiling debate, or the ability for Rick Perry to tout cuts to education as a political virtue, can be plausibly read as extensions of this analysis).

Age of Fracture and Unmaking the Public University end up of pairing quite well together. Newfield has the virtue of examining the kinds of changes that Rodgers describes through the lens of one institution – the University of California system. Rodgers has the virtue of providing an account that accommodates similar pairings with more polemical works in the specific areas he covers (e.g. Richard Sennet’s The Culture of the New Capitalism in the area of economics). But the wide range of topics on which these two books will allow you to speak has the infinitely more valuable virtue of projecting a summer of serious scholarship, despite the fact that we’re more excited about Full Stop’s discovery of the 2012 AWP program.

This post may contain affiliate links.