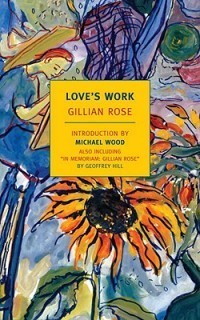

[New York Review Books Classic; 2011]

by Michael Schapira

Gillian Rose arrived in New York City in 1970 after three years of study at Oxford, years which “almost completely expunged” a love of philosophy and literature (one born of “the wager of wisdom” opened by Plato’s Republic and Pascal’s Pensées to a 17 year old Rose). It was in New York, in an intellectual and cultural ferment consisting of rock music, contemporary German philosophy, LSD, homosexuality, and Abstract Expressionism, that Rose began her Lehrjar – her real apprenticeship. For the scholarly community that came to admire Rose, evidenced by the effusive praise and eloquent remembrances of students and colleagues following her death from cancer in 1995, the first mature product of her formation was The Melancholy Science (1978), a study of T.W. Adorno, one of the 20th century’s most enigmatic and difficult philosophers.

In addition to a shared Jewish heritage, one which led each to thoughtful confrontations with what a barbarous 20th century had bequeathed to thought, both Rose and Adorno practiced a seriousness that could be disquieting to their peers. As the poet Geoffrey Hill writes in “Gillian Rose: in Memoriam”: “I find love’s work a bleak ontology to have to contemplate; it may be all we have.” Part of Hill’s difficulty with the work lies in Rose’s refusal to avail herself of the most common forms that society provides to someone living out the final months of a terminal condition. She has little patience for the “junk literature of cancer” that covers “everyone and no one…The case histories sketch no-hopers, saved by cancer. Cancer gives them their last and first opportunity to admit and explore deep unhappiness and chronically unhealthy lifestyles.” The epigraph/injunction of Love’s Work, “Keep your mind in hell, and despair not” (taken from Russian monk Staretz Silouan), should make it clear that we should have no time, especially in the face of death, for such life denying pseudo-affirmations.

Similarly, the title of the book should not mislead us to think that Rose’s rapidly approaching death has allowed her to identify a deeper consummation of the failed loves of one “highly qualified in unhappy love affairs.” Many of the most moving, profound, and evocative aspects of Love’s Work plumb the depths of love’s self-limitations (“there is no democracy in any love relation, only mercy”). The paradigmatic case of failed love is between Rose and an idealistic priest, where the “vast, open space of unpressured love” is closed with the most mundane of phrases – “I hate conversations like this” – and gestures – “He covers his eyes with index finger and thumb.” It is here, in love’s loss, that Rose has us linger:

“This time I want to do it differently. You may be weaker than the whole world but you are always stronger than yourself. Le me send my powers against my power. So what if I die. Le me discover what it is that I want and fear from love. Power and love, might and grace. That I may desire again. I would be the lover, am barely the Beloved.”

Love’s Work can reach highly abstract registers (in the tradition of great minds, like Kierkegaard and Augustine, who cannot uncouple love and faith). This might leave some readers to wonder why a more direct and familiar philosophical memoir was not written so as to assure that Rose has not spent her final labors sewing the seeds of confusion. Yet there is an undeniable urgency in the writing, one which does not come from the closeness of death. Adorno offers us a clue as to why Rose adopted a forceful, though not easily interpretable style in a 1946 piece entitled “Timetable” (a word appropriate to the conditions under which Love’s Work was written):

“But one could no more imagine Nietzsche in an office, with a secretary minding the telephone in an anteroom, at his desk until five o’clock, than playing golf after the day’s work was done. Only a cunning intertwining of pleasure and work leaves real experience still open, under the pressure of society. Such experience is less and less tolerated. Even the so-called intellectual professions are being deprived, through their growing resemblance to business, of all joy.”

The remembrances of those close to Rose attests to the fact that she too could not be imagined easily slipping into the “deprived” experiences that drain seriousness not only out of labor and leisure, but of our relationship to death itself. It is this that solicits both respect and disquiet from Geoffrey Hill and Michael Wood (who writes the introduction to this edition). The republication of Love’s Work (sixteen years after it was released to great acclaim) should not be taken as an attempt to acquaint a new generation of readers with guides for living from a very smart and insightful woman. Rather, we should celebrate this republication for calling forth a seriousness that is still imperiled by the pressures of society.

This post may contain affiliate links.