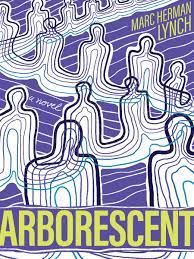

[Arsenal Pulp Press; 2020]

From its elaborate prose to the narrative content, Marc Herman Lynch’s Arborescent luxuriates in the space between the familiar and the fantastic, dipping into both ends of the spectrum to paint a richly layered contemporary folk tale. Each character is linked to some cosmic gift or curse, whether they serve as a host to an all-consuming tree of life, embody undead spirits of vengeance, or have borrowed charisma and luck from the stars themselves. Lynch seems interested in exploring the poetry of prosaic working class life, uplifting his otherwise ordinary protagonists with the shimmering threads of supernatural possibility and the beauty of the book’s own elevated language. While the struggles that bend the protagonists’ narrative arcs seem to be grounded and mundane (such as the frustrations of repetitive social interactions with unpleasant and selfish people, or the thankless grind of running one’s own small business, or the numbing aftermath in response to a loved one’s death), the deeply physical lyricism of Lynch’s prose gives them such crushing weight that all the characters can do is yield to the supernatural forces that await them — a fate that seems as inexorable as the burnout that any of us might experience when ground down by the relentless toll of societal pressures.

Overall, the structure of the book is broadly accessible, taking form as a collective slice-of-life portrait of three primary point-of-view characters: Nohlan Buckles, Hachi Yoshimoto, and Zadie Chan. There is nothing linking these characters in their personal lives, except their shared working class background, represented through each of them living in the residence of Cambrian Court — a run-down, eighty-year-old apartment building described as “a halfway house for the bedraggled, existing as nothing more than a half-hearted commitment to historical preservation.” Each of the three characters are stalled in this place, stuck within monotony and just outside the edge of some kind of brilliance that they believe would make their lives more exciting and exceptional. In Nohlan’s case, he feels mediocre beside his father Jeb’s shining star; Jeb, the point-of-view character of the book’s prologue, had a career as a local celebrity, and even his downfall and death are two distinct acts of outstanding spectacle that outshine everything Nohlan has accomplished for himself. Hachi yearns for the actualization of her artistic dream (her deeply personal vision of the classic kabuki play, Yotsuya Kaidan), which continues to gleam just out of reach while it haunts the corners of her consciousness. Zadie, a teenager, must remain in limbo at the whim of her mother, who refuses to move on from the pursuit of prosperity she feels entitled to, draining herself in a legal crusade to reclaim property and assets from her recently deceased lover. Instead of achieving any fulfillment or freedom that these examples of brilliance would give, the protagonists remain mired in routine for much of their narrative.

That inescapable sense of monotony becomes almost visceral through the emphasis of the deadening cold of winter that permeates Lynch’s prose. The only relief that these characters experience is that of a warmth-bearing chinook on its way — and even then, they know that it will pass quickly and become cold again. This persistent, chilling ache of loneliness and yearning is an antagonistic force for the majority of the book, albeit an internal one. Even the characters who have closely established relationships with those around them — Hachi, with her group of friends and kabuki cohort, and Zadie, with her kind and supportive grandfather — experience some form of emotional isolation as they turn away from any healing warmth they might have found, such as if Hachi had confided in her ex-girlfriend about the traumatic assault she experienced, or if Zadie had chosen to live in the safety of her grandfather’s home instead of remaining with her obsessive mother. The protagonists may take some actions to resist — as when Nohlan pushes past his insecurities to pursue his connection with his unrequited crush Psychic Celine — but that gnawing isolation is otherwise an inevitability in their lives, like the cold of winter that returns after the chinook ends.

While loneliness thickens around each of the three characters in a thematic way, there is a far more tangible antagonistic entity that lurks in the crossroads of their lives — the landlord of Cambrian Court. Throughout, he is presented as a symbol for the ruinous, uncaring philosophy of late-stage capitalism; he feels entitled to his residents’ full attention as he preaches about his hierarchical ambitions and consumes a never-ending supply of his chosen snack (pistachios). However, as a potential reductive representation, it is just as easy to dismiss him as a layer of unappealing flavor to the overall picture of his decomposing property. While Lynch does nothing to hide the landlord’s ogreish nature, he is careful about how frequent and impactful his appearances are. The build to his true narrative power is intentionally gradual so that, in the climax, the landlord becomes a significantly more grotesque threat than he first appeared to be — as if literally inflated and empowered by his constant consumption, the reward of a predatory land-owner whose only purpose, it seems, is to stalk his renters’ steps and demand compliance and payment. It is somewhat of a surprise, but not an unwelcome one, that the narrative pacing accelerates to confront the landlord’s monstrous metamorphosis. Perhaps Lynch is suggesting that it is dangerous to overlook or sidestep the threat of those who seek to control others, lest they become unstoppable while their “prey” are wrapped up in the minutiae of their everyday lives; or perhaps this confrontation was always inevitable for those unfortunate enough to fall into the desolate existence of living in a purgatory like Cambrian Court. Regardless, it is more engaging and satisfying to read about a final battle against a single loathsome character than to try to envision challenging the more symbolic spirit of persistent depression.

At this point in the story, the internal threat of all-devouring loneliness has become external, particularly for Nohlan — in whose case it is subsumed by an enormous tree that grows rapidly from a seed in his stomach, with the questionable astrological guidance of Psychic Celine. Rather than the tree of giving life that Nohlan believes it to be, the tree is a parasite, a vampire even, that confines him to his bedroom and isolates him even more than he was before. Nohlan’s sense of self has deteriorated so completely that he believes this gives him a grander purpose, in essence, transmuting his only value as a person to nothing more than a physical entity that remains rooted in a single room — not so unlike how any landlord would see him, simply a warm body to fill an open space and pay rent. No longer does he make an effort to improve his circumstances, but rather tries to find meaning in being immovable, as if surrendering to a state of eternal arrested development. Nohlan’s tree grows rapidly so that he no longer has to.

The physicality of all the main characters is emphasized, and it is their bodies that gain exceptional significance as vessels of supernatural purpose — perhaps as a way to demonstrate the undeniable influence of the fantasy genre on this otherwise realistically grounded universe, to signal that such forces have literal effects on the story as well as being figurative motifs. In addition to Nohlan’s tree, there are the stars that inhabit Jeb Buckles’ chest — which are implied to be what made him successful in the first place — and the myriad of animated body duplicates that Zadie Chan becomes and possesses in her vengeful afterlife. But none can escape the consequences of their physicality less than Hachi, who faces objectification by nearly everyone she knows. She is observed singularly, as her body, whether that be due to her Japanese ethnicity, her expressions of femininity and queerness, or her intricate arm tattoos. This hypervisibility reflects a cruel reality that Asian women are constantly subject to in misogynistic and racist society — and Hachi is grimly no exception. There is certainly value in challenging readers to face such uncomfortable truths, but Hachi’s treatment is sometimes too painful to witness, particularly when the perception of her physical desirability leads to sexual assault — an all-too-common occurrence in our, Asian women’s, known reality.

The writing of the assault is jarringly realistic, and to process this, the book leans into its fantasy conceit to handle the consequences of this heinous act, actualizing the ghost character from Yotsuya Kaidan to carry out vengeance against Hachi’s attacker. This harrowing twist, while certainly intriguing and satisfying in the context of folklore, falls short of our contemporary standards of justice. This is a moment that deliberately signals a gear-shift of the book’s genre from outlandish, fabulist realism to outright fantasy; but it is difficult to let go of the desire to see a more thoroughly sensitive depiction of recovery and support for Hachi. After all, it is still rare these days to see well-rounded queer female Asian characters in the driver’s seat of their own narrative, so one can’t help but wish for more demonstrative agency throughout Hachi’s entire arc.

Similarly, Zadie, who is also Asian (Chinese), is unable to optimize her own agency until after her untimely death, when she returns to inhabit seemingly not just one, but many body duplicates of herself. It is an unexplained gift of the universe, and she uses it to her advantage; but in life, her efforts to improve her circumstances, and those of her grieving mother, are stonewalled. Zadie, who is the final point-of-view character in the book, benefits from the breathless pace and fantastical high stakes of the climax, and perhaps it is no coincidence that she loves poetry and views words as her tools. It seems as though the prose itself comes together for her to wield, tightly spun and vividly imaginative, as Zadie must collect her various selves when awakening after her death:

A collective cry emerges as Zadie watches herself, mute and blind, rise from the casket; she’s dissociated from this body, watching from afar, as it clambers, hands patting at the marble steps crawling up the altar, managing to get to her feet like a newborn faun on stilt legs. […] Rubbing her eyes, her double plucks cotton packing out from under her eyelids, and suddenly, Zadie is gazing out from this body, watching the remains of the congregation flee in terror before her.

She tries to open her mouth but can’t; the pressure mounts in her nostrils and her lower jaw as she forces a yawn, like a lioness, until the string that tethers her jaws breaks. The cotton stuffed into her throat tastes of coconut hand cream.

While Zadie reassembles herself as a multiplicitous being with singular purpose, so too does the narrative, intentionally weaving the many threads of each character’s experiences into the final confrontation within the confines of Cambrian Court. No longer is the reader following a meandering recount of these characters’ everyday lives as they are flanked by the unexplainable and the weird; now it is a boss fight, a battle of wills, wherein Zadie and Hachi reclaim their lost agency, and Nohlan loses his tenuous grasp on his. Ultimately, the narrative uplifts Zadie’s victory most of all, and the last paragraphs of the book are unabashedly meta in recognition of her empowerment through words: “Through rhythms shaped by enclosure and fear, she can produce a fourth dimension, carving words into time and space like a metaphysical relief.”

The superpower of actualizing language may be true for Lynch as well, who undoubtedly demonstrates deft skill in evocative vocabulary and descriptions. In that sense, then, Lynch consistently shows readers how much more beautiful and strange, haunting and spectacular, a mundane, lonely existence could be than we may initially perceive it to be. Through the glow of artfully chosen words, woven into both ordinary and extraordinary worlds, Arborescent stays true to itself throughout all its genre-shifting transformations.

Maya Stroshane is a speculative fiction writer living in Boston. She is a graduate of Brown University, where she received the 2011 Frances Mason Harris Prize for the best book-length manuscript of poetry or prose written by a woman. She is currently revising her first novel.

This post may contain affiliate links.