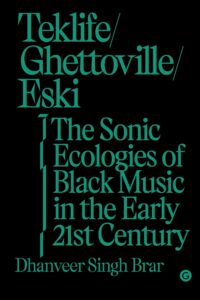

[Goldsmiths Press; 2021]

Dhanveer Singh Brar’s Teklife, Ghettoville, Eski: The Sonic Ecologies of Black Music in the Early 21st Century provides an analysis of the various genres of black electronic music, such as Footwork, Actress, and Grime. Throughout the book, Brar shows the way in which this genre has been policed and explores the numerous attempts to frame it as pathological due to the fact its practitioners came from impoverished neighborhoods. It was music largely performed by black people, and because of this, most of the musicians faced racialized policing within a context of economic and social isolation. Black electronic music was off the radar, secretive, nomadic, creative, imaginative, not bound by walls, codes or laws. It created a rupture in the system that produced, according to Deleuze, a “map of creative imagination, aesthetics, values…animated by unexpected eddies and surges of energy, coagulations of light, secret tunnels, and surprises.” For this reason, black electronic music and its producers were framed as unruly, deviant, and as Brar writes, “replete with behaviors said to offend common precepts of morality and propriety, whether by excess (as with crime, sexuality, fertility) or by default (in the case of work, thrift and family).”

Techno musicians, in the mid-80s, conceived of sound as evoking interplanetary dimensions; they imagined a futuristic city “as spatial as it is temporal.” The writer, theorist and filmmaker Kodwo Eschun writes in New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement (edited by Lisa Gail Collins and Margo Natalie) “that Cybotron’s (the brainchild of Juan Atkins and Richard 3070 Davis) track, ‘Techno City’ (1984) is a futuropolis of the present, planned, sectioned and elevated from station to studio, transmitting from a Detroit in transition, from the industrial to the information age: Cybo [rg] + [Elec] tron [ic] = Cybotron…Cybotron is the electronic cyborg, the alien at home in dislocation, excentered by tradition, happily estranged in the gaps across which electronic current jumps.” It is like the Big Sonic Machine coming apart, re-programmed, hacked, to create a new language from the burned circuits of Western diatonic music. It is still idiomatic but the idiom is from a stranger land, another dimension. This rich, vivid music opens up a network of passages into other space stations of sound. There are connection points, drifting subatomic explosions of sound. Gravity is at times suspended. There are halts, a sense of weightlessness during transport. Then signals, signals to turn, enter Elsewhere. New dances form new bodies. During his life, American jazz composer Sun Ra would also evoke the idea of a futuristic city in space at a time when the civil rights movement was coming up against the dominant powers. In the 1974 film Space is the Place, Sun Ra and his Arkestra claimed: “Outer Space is a pleasant place. A place where you can be free. There’s no limit to the things you can do. Your thought is free and your life is worthwhile. Space is the place.” Thus, in Techno, Brar writes there “was the ability to sonically image space travel and the emotive capacities of new industrial technology.”

In the 2000s, the Footwork genre emerged from the Techno scene and some of Techno’s elements can be seen in the moves of its dancers and their sense of aesthetics. Footwork is a genre characterized by fast and yet precariously balanced dance steps which simulate a kind of robotic movement that is frenetic and wild; these dances took place in a space that was called “the battle circle.” Brar writes,

Footwork battles can take place in almost any setting across Chicago’s South and West sides, ‘a sweaty vacant warehouse, a school gymnasium, a rec center, a house party or an El train platform’ (Dave Quam,‘Battle Cats: From the Rise of House in the 80s to Today’s Juke and Footwork Scenes, Chicago’s Circle Keeps Expanding’, XLR8R, 9th August 2010, www.xlr8r.com/ features/2010/09/battle-cats-rise-house-music-80s.)…On any given battle two crews will assemble, along with a crowd and a DJ, to compete, with the stakes being reputation, money, or both. The crowd forms a circle, with the two teams facing each other. Individual members take turns to step in and do battle whilst the DJ sets the terms. What makes Footwork battles compelling is the range of furious movements of feet and legs that the dancers produce and demand from each other.

This passage reminds me of the Rave scene in New York and Chicago in the 90s and how the venues dancers chose to practice their trade in were secret. It is in these underground laboratories that Footwork musicians were fashioning their own identity, as well as a new sound and dance, like contemporary sonic alchemists. The music of Footwork is sped up, and it works its magic through a series of incredible syncopated drum patterns: flurries and clusters of kicks, snares and toms, with a splash of micro-chopped samples, either sped-up or slowed down.

An important idea formulated by the Footwork artists is Tek. Brar, explaining the concept, writes, “Its [Footwork’s] phonic materiality has been theorized by Footwork artists via the formulation, Tek. They self-identify as Ghettoteknitianz, they declare themselves to be Architeks, and they conceive of their social relations as generative of Teklife.” The music can be understood as “a restless architekture, assembled through the dimensions of dance and rhythm, race and class.” Furthermore, this declaration of Teklife symbolizes a marking out of a lifestyle that would move away from the industrial toward the informational and the technological, toward the vast web of the digital world; in their dance movements, the Footwork artists embrace an aesthetics of speed. Furthermore, Brar points out the relation between dance and the envisioning of a city mirrored in the Architekture of the body as it moved in the “battle circle”: “the accompanying Pythagorean alignment of upper limbs and torso operates as a repurposing of turned over ground, to the extent that the battles start to generate choreographic designs for buildings that await realization.” This is what is meant by a sonic ecology; it is a quality that all the musical genres described in this book share: to a greater or lesser extent all the producers of this music relate to each other and their environments, envisioning an alternative space inside their neighborhoods, far from the financial world, and whose foundation is a new kind of Architekture. But all this occurred during a time of unrest within the poor neighborhoods on the West and South Side of Chicago, which incited the anger of those who were interested in maintaining their territories through law and order, leading to the repression of these musicians from the outside, because internally they seemed to flourish.

The electronic musician Actress, in opposition to Techno and Footwork, imagines the city as a place here on earth. While wandering through the streets of South London he speaks of the various things he has seen, “zooming in on the immediacy of the environment around him in South London.” Actress describes his music as emerging from natural processes he observes. He transforms his quotidian observations (watching leaves falling to the ground, and looking at the concrete of the surrounding industrial landscape) into abstract sounds. Brar writes about Actress’ soundscape, that it is “rendered through the perception of, and absorption in, a range of activity in his immediate geography, which is then digitized into sonic effects that are not photographic, but a distillation of the relations between material phenomena.”

A listen to Actress’s album Ghettoville reconfigures one’s sense of what music is. The sound is enigmatic, evoking an industrial space, with rhythmic repetition and variations of the voice, electronically modified, and then on some tracks, there’s humming or a fading into the distance. It’s music for the mind as much as for the body: the dance. It’s music for what is. It shortcuts rational cognition; takes you someplace else. Sounds are not fixed but serve as points of departure for different sounds. Actress is a navigator of the sound spectrum. With two feet planted firmly on the ground, the music will carry you, clearing one’s perceptive window. It’s meditative and danceable; atmospheric and abstract. There’s a strong sense of process and flux, like a sculpture made of plasma rather than stone or bronze. As the female voice repeats on “Don’t,” track 13: “Don’t stop the Music.” Though Actress’ sound is rooted in the real world, in terms of its sonic materiality, this does not mean the music is fixed or stable; Barr writes that Actress is “attentive to the minute composition of immediate environments.” Actress, as opposed to Footwork and Grime, operates as a soloist in part. The intensity of revelation and Actress’ effacement of the self, leaves in its wake the permanent invisible, the luminous, which is in the sound.

The music known as Grime developed out of the earlier dance style, UK Garage. As Brar writes,

it was forged in the crucible of East London in approximately 2003. It was here that the sound which eventually came to be known as Grime was cut and spliced into shape, within the context of economic and social isolation from a city experiencing the boom economies of market-driven governance – a dynamic doubled down by the intensification of racialized policing.

The music is often jagged and aggressive, with syncopated breakbeats of around 140 beats per minute. The music can be abstract but it is also a raw and sometimes bleak sound. The man behind the music, British rapper, songwriter, and DJ, Wiley, grew up in Clare House, a cold, industrial, and sometimes violent area in East London. Unlike most American cities that segregate the rich and poor over large geographical areas, London is a city where the council tower blocks (similar to housing projects in the US) are situated alongside large mansions within a single borough. This proximity fueled the increased policing and surveillance of black men living in poor neighborhoods, the result of which was a growing tension between the Grime artists and figures of authority. But Wiley proved that from that bleak world, and against the violence and frequent harassment of the police, he was able to create vital music despite the odds stacked up against him. Indeed, it was a sound that grew out of the Grime.

In Grime, the lyrics are spoken very fast and since they are so, as Brar writes, “simple and direct, it has the effect of simplifying and abstracting the messy violence [as the result of police aggression against the Grime artists and also the violence contained in the lyrics] into a flow of code, boasts and bravado.” MC’s, such as Dizzee Rascal, work to protect their status and reputation against any threats; while the existence of the potential violence inflicted upon their community is generated through “the form, structure, and contours of the lyrics.” Derek Walmsley, editor of Wire, clarifies, in his comparison of hip-hop and Grime, the nature of this violence in Grime’s lyrics: “There’s a recurring paradox at work here, which is that Grime, by referencing violence and war so much, seems to blunt its edge…MCs can be bitter rivals on record but friends in reality. Disputes and threats are generated in a sphere completely separate from any real-life dispute…Allusions and references to violence in Grime should never be taken at face value, but must be understood on their own terms.”

The producers of Grime also used pirate radio to relay the sounds; this led to improvisations over the airwaves. Because of this, they came into violent conflict with the OFCOM (Office of Communications – the UK’s government-approved regulator of broadcasting and telecommunications). This genre of black electronic music was considered by external forces as antagonistic, and potentially violent. As Brar writes:

The blackness emanating from Grime-pirate radio was placing in severe jeopardy the terms and conditions of race as a spatial epistemology in London, and it was doing so by way of its carefully crafted use of violence. This is why, as a form of black music, Grime induced such intense levels of racialized policing…it manifested itself as a war machine of blackness whose primary object was its own continual flourishing.

These Grime artists not only encountered the forces of dominant powers in the form of police violence but also through the attempted repression of their sounds by those in charge of broadcast regulations – both of whom saw them as a threat, which, as Brar suggests, was amplified since the musicians were black. Given the recent murders of George Floyd, Rodney King, and Michael Brown, Brar’s examination of the frequent policing of black men is an important and timely aspect of this book. I also think of the immigrants fleeing a country at war and seeking asylum in the United States, and the way they were treated under the previous administration, where children are unfed and unbathed, where people live in unsanitary spaces or rather, in prisons. As long as they are not American citizens – i.e. white, naturalized – and do not exist within the supremacist “white” narrative, they are unable to mobilize effectively. It is this fear of the mobilization of these black musicians, as Brar notes, that caused the authorities to act.

The Footwork, Actress, and Grime scenes all suffered from racialized violence because of their marginalized status, because they were poor and black, and their music was perceived as a profound assault on Western ideas of music and dance. Brar writes that these genres of music “are all styles that can be given to the general category of black music, and they are also musical forms which are materially, socially, and culturally – to varying degrees – determined by a relationship to concentrated areas of economically precarious, racially encoded urban inhabitation in the Global North during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.” Brar effectively shows that despite the aggression on the part of the police, these movements flourished in their sonic studies and activities. They developed new and original sounds, dance movements, and ways of envisioning a new kind of city; they were staking out their own territory, despite “the gloomy observations of the statisticians and civic leaders” who think they understand the Black Ghetto and the sounds and community that are born there. Dhanveer Singh Brar’s Teklife, Ghettoville, Eski: The Sonic Ecologies of Black Music in the Early 21st Century marks an important step in understanding the value of this music and how it allowed these black electronic musicians, DJ’s and MC’s to prosper against all the odds.

Peter Valente is a writer, translator and filmmaker. He is the author of eleven full-length books, including a translation of Nanni Balestrini’s Blackout (Commune Editions, 2017), which received a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly. His most recent book is a co-translation of Succubations and Incubations: The Selected Letters of Antonin Artaud 1945-1947 (Infinity Land Press, 2020). Forthcoming is a book of essays, Essays on the Peripheries (Punctum Books, 2021), and his translation of Nicolas Pages by Guillaume Dustan (Semiotext(e), 2022). Twenty-four of his short films have been shown at Anthology Film Archives. He is presently working on editing a book on the filmmaker Harry Smith.

This post may contain affiliate links.