[Rixdorf Editions; 2018]

[Rixdorf Editions; 2018]

Tr. by James J. Conway

I’m accompanying my wife on a work trip to Salt Lake City, and the owner of our AirBNB (charmingly) waited until after we had checked in to notify us by text that the apartment is currently enduring a minor infestation of boxelder bugs. They are slow, ambling things around the size of a lentil; they clump around the outside edges of windows, trying desperately to find a navigable crack in the weatherstripping to escape the three-digit heat of July.

I’ve brought Anna Croissant-Rust’s Death with me, but have instead found myself engrossed in a book from the apartment’s shelf: Massacre at Mountain Meadows by Walker, Turley Jr., and Leonard. Taking cues from the 1950 Juana Brooks study, this 2008 work strives for a definitive, unbiased account of an extremely dark moment in Mormon history; truth-telling as a step toward reparations. Its authors enjoyed the uncommon combination of both unfettered access to the LDS archives and complete editorial independence; they exhibit a care for detail which extends into the realm of engaging a “a rare specialist in transcribing nineteenth-century shorthand” to examine court documents which they suspected were quoted inaccurately in John D. Lee’s 1877 autobiography (written in prison while awaiting his execution).

In the late 1850s, adjacent to the ominous churn of “states’ rights” in the South, a series of escalating conflicts between the theocratic leadership of the Mormon settlement in the Salt Lake Basin and Utah Territory’s federally-appointed administrators had strained tensions to a breaking point. The federal government cut lines of communication to the territory and sent an army westward, the beginnings of what would later be called The Utah War.

Seized by paranoia over the impending conflict and fueled by apocalyptic sermons from Brigham Young and other church leaders, the Mormon settlers in Cedar City were on edge when a California-bound wagon train passed through. The emigrants from Arkansas and Missouri brought bad blood and loose talk; rumors of cattle poisoning carried the situation to a head. Local militias began to discuss extreme measures, unwilling to wait for a dispatched postal rider to return from SLC with further instructions.

John D. Lee, a militia leader, enlisted the nearby Paiutes — thereby providing the needed cover of an “Indian attack” — to ambush the emigrant train outside of town at a grazing waypoint. The emigrants circled the wagons and dug in for a four-day siege, while militiamen from around the district mustered at the site. Finally, under a false promise of clemency, the 120 surrendering men, women, and children of the caravan emerged, unarmed. The Mormons waited until they were stretched into an indefensible line to start firing.

The book opens with an 1857 account by Brevet Major James Henry Carlton, later tasked with traveling from California, across the Mojave desert, to give the bodies a proper burial.

“The scene of the massacre, even at this late day,” he wrote, “was horrible to look upon. Women’s hair in detached locks, and in masses, hung to the sage brushes, and was strewn over the ground in many places. Parts of little children’s dresses, and of female costume, dangled from the shrubbery, or lay scattered about. And among these, here and there, on every hand… there gleamed, bleached white by the weather, the skulls and other bones of those who had suffered.”

I think about this as I accidentally jostle a window frame, and a dozen stupid bugs tumble out into the sill. I ball up a paper towel, and slide it along the track, crushing their frail bodies into one another, before tossing it in the garbage. They don’t compost here.

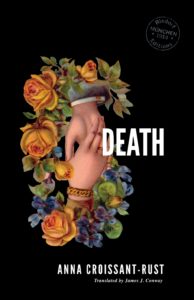

I’ve been thinking about death a lot. It’s hard not to when you’re carrying around a small, black volume wearing its name. Talismanic, handsome, compact — you can tuck Death snugly into your back pocket as you transfer from the bus to the underground rail. This book arrives courtesy of James J. Conway’s Rixdorf Editions, a young Berlin press dedicated to delivering inaugural English translations of material from the German Empire (1871-1918), showcasing the “unfairly neglected” works of progressive writers, “advocates for female emancipation, sexual minorities, lifestyle reform and utopian visions.”

Croissant-Rust’s writing career began around 1883, when her family relocated to the Shwabing district of Munich. After becoming acquainted with Michael Georg Conrad, in the late 1890s, she became a founding member — and the only female member — of the Gesellschaft für modernes Leben (Society for Modern Living). Together with this group, she worked primarily in the style of Naturalism, which “coincided in time and sentiment with the Modernismo movement in Latin America and Spain, and overlapped with the first phase of Anglo-American Modernism.”

Her works pushed the group further into the avant-garde, freely merging, bending, and breaking traditional poetic and prose forms — into a territory only a few scattered authors in her influence had before. Along with this literary experimentalism, she used her work (plays in particular) to advance women’s causes. When marrying in 1888, she chose to elide her surname with her husband’s, rather than replace it entirely; he supported her writing career, reading drafts and helping to secure publishing.

This book includes not just the titular collection of short stories, but also an earlier volume, Prose Poems, written between 1891 and 1893. Of the two, Prose Poems is the more radical and uneven: both within and between pieces, the style shifts chaotically from lucid paragraphs to unpunctuated abstraction. This earlier work explores the broad splashes of interest which would eventually distill in Death; many include a fascination with states of decay, both in nature and psychology. But we also receive uninhibited forays into female lust, psychedelic wanderings where the natural world melts into the personal interior, and a depiction of a storm overtaking the landscape explicitly rendered as masculine sexual violence — the text splinters into ragged edges which would eventually be sanded down with age into more subtle expressions.

Where Prose Poems succeeds — in haphazard, abbreviated ideas; words tumbling quick like drunk texts — it feels a good half-century ahead of its time. And its occasional contrasting stumbles — in overlong, samey passages once again lusciously painting meadows and streams in thick gouache — serve to highlight the interesting mix of ideas fueling its creation. That it was met with critical befuddlement seems almost a given.

Death was published two decades later, in 1914, as Croissant-Rust was into her 50s, and the Empire was holding its breath before the plunge into The Great War. It is a collection of 17 short stories, circled and jigging in the Danse Macabre. Death might arrive in his spoopy formalwear, a skeletal grin wreathed in black; or as a laughing wave of fire sweeping along the walls of a packed, panicked theater; or silently, invisibly, in terrifying realism, as the body simply ceasing to breathe — but death will always arrive.

With time, Croissant-Rust has folded her experimentalism into a more fluid syntax; though many of her passages still carry the wandering, unexpected flavor and satisfying waviness of poetry. The natural world remains ever-present; even in cities, it saturates the language, twisting up like vines between cobbles, sprouting like lichen on the brickwork; the page swirls alive with the acid nightmares of DeepDream.

Cloud dogs race across the sky in a thick, grey-black pack; the hunt grows wilder, the pack grows larger and darker and thicker until it tumbles over itself in a confused bundle and collapses into black darkness.

“Corn Mother” is the story I kept returning to. Racked with fever, a child watches the stalks wave and bow in the field beyond her window, as the rest of the world dozes silently in the white blaze of a heatwave’s afternoon. Here, Croissant-Rust freely intermingles the spinning flights of childhood with the reader’s growing anxiety at knowing how the story must end; the inescapable brightness of noon provides no cover for either of us, as the Corn Mother arrives haloed and fecund like the Waite-Smith Empress.

Other stories veer into the morbid theatrics of black metal filtered through an early feminist lens. “The Ball” begins with “An elation of violins rid[ing] high on the drunken, giddy pleasure,” as a young belle is carried, in the vortex twirl of the waltz, inverted, to the ceiling. The lights “become suns… sizzle up like snakes, turn cartwheels like peacocks, rush up to the ceiling and tumble back down, red and hissing.” As the dance whirls inevitably into darkness, Death, tonight a gentlemen, thanks the belle “with a little swivel of his chapeau claque.”

“Shadows” is even more explicitly, cruelly allegorical. Returning from an evening out, a young woman becomes entranced by the hypnotic beauty of her own reflection; enveloped in a lust which morphs into self-worship. From the mirror, a pair of glowing eyes breaks the spell with sharp terror. Finally, “small, cowering, pleading, she lies on the floor and struggles with the shadow that casts its great cape around her, burying light, burying youth, burying beauty.”

But death meets others kindly, sweetly; in the overgrown gardens of fading estates; in an unending stream of messages encoded in the language of flowers (which, being unfamiliar with the German manuals of the day, remain, to me, opaque). Here, in “Midday,” the fading mind of a town’s last anachronistic noble flutters backwards to his golden prime, materializing ghosts of his passionate affairs in clouds of fragrant lilac.

Toward the end, a strange turn brings the book’s form into question. An ill wind, the Föhn, blows through three sequential chapters, the only such connection in the book. And as the Föhn’s twisting weirdness circles its unfortunate chosen, it also reaches into the text itself, bending the last two stories unexpectedly into first-person narration. A mother cradles her child in the last moments; tracing scenes from an unlived life in a downpour of impassioned, hallucinatory pleas; And an individual looks back on a night long past, where, in this very room, six children were taken by sickness — the adults who survive them remain broken, racked with guilt and bitter secrecy.

Death is a wild book. It’s wild — structurally, linguistically, sure; in particular, its mix of romantic 19th c. diction (torpor, imperious, etc) twisting into anarchic 20th c. syntax — but what I mean specifically is this: It reminds me of those rare encounters when you’re out for a run in the park, in the morning, and you turn down a path through the trees, and then, suddenly, there’s a coyote right there — You stop, the coyote stops, and you both just freeze, eyes locked, waiting for the moment to break, or something to break the moment, wrapped in a weird communication through mutual silence.

I carried this book around, ignoring it as it tailed behind me; now that I’m finished, it lingers, refusing to settle into finality. Refusing to turn back into the tangle of ferns below the slanting treeline. Instead we stay motionless, each waiting for the other to blink. I keep slipping it into my pocket when I’m heading downtown.

Devin Smith is a musician and writer in San Francisco. See his website for a full list of projects.

This post may contain affiliate links.