“There are questions we could not get past if we were not set free from them by our very nature.” – Kafka, in an unpublished fragment.

This past year, Full Stop spoke to poets, novelists, essayists, writers of historical fiction, philosophers, musicians, filmmakers, and others who are more difficult to categorize. The range of topics even outstripped the range of interlocutors: we explored the nature of a fictional voice, designations of place — what it means to be a “Western writer”, a “Peruvian author”, an “American” — the power of a heartfelt comic, the character of communes of the 1960s and 1970s, the intensity of birth, the challenge of a feminist perspective in historical fiction. Here’s a look back at some of our favorite, most thought-provoking, funniest, and weirdest conversations of 2013.

I like to read novels where the author seems knowledgeable; like someone you know you could walk calmly next to through a complicated situation and he or she would be alive to its meaning and ironies. And you wouldn’t even have to mention them out loud to each other. A writer who cares about the world and about the smaller but not insignificant details that can be cracked open to find humor and meaning. That’s how I like to feel when I’m reading and what I try to go for when I am writing, in the sense that I want to activate what I know but in a manner that is organic to the narrative, and not simply knowledge for its own sake.

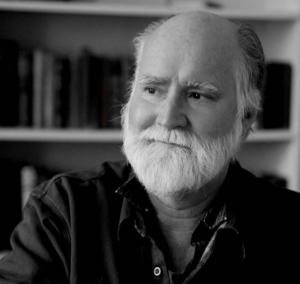

Photo credit: Aaron Levy

Hamlet’s desire is massively inhibited, whereas Antigone is that creature who just has desire, the desire to see justice done for her dead brother, and Ophelia is like that. The death of her father unleashes a genuine madness. What is voiced in that language isn’t the kind of intelligent dissembling of Hamlet, it’s a kind of raw madness that actually bypasses language. Hamlet has words, words, words — the boy can speak — and Ophelia can speak too, but when she goes mad, she starts to speak with songs and flowers. In many ways, the play is about the emptiness of language. What are these things called words? What are we doing? Is language just a way of hiding the truth?

Books and movies are so skewed towards action. You get fired, and that’s the inciting incident, or your wife leaves you, your husband leaves you. You come into some money. You are suddenly mistaken for a CIA operative. Something happens that is completely out of the blue, and you’re expected to have wise, thoughtful reactions to it. But actually, you’ve just become a person who is sort of running and keeping up. I don’t believe that whole thing of: Get the character in a tree and then throw stones at him. I don’t buy it. It’s a very bad piece of advice.

The spectral being, the missing mother, or father, or sister, is what drives this book. What is a search if not a search for the missing? And the search is the essential story, no? The thing that drives. From Telemachus’ search for his father, to the grail, to Freud’s internal quest back to a primary instance, which doesn’t have to have ever existed, he tells us . . . as long as a story can be made to rise up around it . . .

The truth is I probably wrote Crapalachia so I could forget those people. I know people might think it is about remembering, but it’s not. It’s about forgetting. I just want to be rid of them. God, I want to forget them so bad. I’ve never been able to let go of anything though really. Wish I could. I kept a leaf one time from this tree at Mount Vernon. I was in the 4th grade when I picked it, and I was a senior in high school when my mom made me throw it away. I wanted to remember what a great day it was and be reminded how much I appreciated them taking me.

I can’t even get rid of band-aids from the people I love.

Photo credit: Basso Cannarsa

The idea of war is more compelling for me than actual war. It’s more frightening, too. Even the lone story that takes place in combat, “A Brief Encounter With the Enemy,” has very little war in it. It’s not the specific war that interests me, but rather the cost of being constantly engaged in war, whether it involves deploying, returning, or watching it on television. What does ten years of violence do to the psyche of a nation?

The reader who is interested in liking characters is just not going to be my kind of a reader. If they can’t like a character because that character has a bunch of flaws or they’re doing something wrong, what does that say? Who are these people? Forget about characters in books, but if I didn’t like humans in general, and I didn’t like them because they had flaws, or were in trouble, then I wouldn’t have any friends. Where are these mythically perfect people?

Where does “voice” come from, to whom does it belong, within any passage of prose? When it can resonate at once from multiple sites: author, narrator, one character or another — sites that themselves are never truly distinct. They are only as distinct as each sentence proposes they be, a game whose rules any sentence can renegotiate. Fictive characters don’t have bodies to speak from, so the idea of “voice,” as it might resonate from any body other than the author’s, is myth, game, fiction. The sentences propose a character and the character proposes more sentences. At least this last is how it feels to me, that each sentence has a way of suggesting a character and one writes instinctively in response: who might speak this? Who would see this or put this this way? And what if this comes next? It’s hard at any moment to know where the language is coming from and where it’s going; what forms it wants to echo off of; whose language this is. This is why I phrased my question as one of “forces of sound” and “forces of character” — as we write we are subject to both, and though we may momentarily harness them, they are so much larger and older than us, and as they push us around we may not even be able to tell them apart (if, that is, they are different at all).

Photo Credit: Adrian Kinloch

I remember the first book that really pushed me was Notes from Underground. That was a big deal. There were others. There were waves of reading. I remember with great fondness — and I’m sure that every big reader has this moment — there’s a part of your reading life when you don’t know enough to be a snob. So you read The Bluest Eye, and then you read Archie Comics, and then you read Philip K. Dick, and then you read The Firm, and then you read The Sound and the Fury, and then you put it down because you don’t understand what the fuck it’s saying. At the same time you’re reading Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, and you still have a little crush on Ramona Quimby, but you’re also reading The Unbearable Lightness of Being because your sister gave it to you and said it’s about sex. There are just no boundaries between high and low and genre and literary, and it’s great. It’s only later that you start saying, “Oh, I never read that.” Well, bullshit. Of course you read it. And you liked it, too. I liked all those books.

The question is, if morality ceases to matter when everyone is going to die soon, then when does it matter? Because (spoiler alert), everyone is going to die — maybe not soon, and hopefully not in a spectacular astronomical cataclysm. But life ends in death, for all of us, and so why do we ever do anything other than what we want? Why don’t we all just do drugs, hang out, have sex, eat cake — hey, man, you only live once, right?

“Morality” is a way of saying that just because life is short and ends in death doesn’t mean it should be a bacchanal of self-indulgence. At some point we figured out that there are deeper satisfactions to be gained, more long-term pleasure, and that availing ourselves of them requires trading some of that cake-eating and drug-doing for law-obeying and mortgage-paying and lawn-mowing.

So to a certain extent, Sam, you’ve answered your own question by waking up this morning and not murdering your enemies, or having a Hostess Cupcake and a forty-ounce for breakfast, or anything else that would give you immediate pleasure. All our lives will end one day, maybe sooner than we’d like, and yet we abide by laws, written and unwritten.

This post may contain affiliate links.