About two weeks ago, the International AIDS Conference wrapped up a week-long gathering of global luminaries in public health and immunology. Much attention was given to the organizers’ choice of location — not only the United States, which hadn’t hosted the conference in 22 years, but its capital city of Washington. Attendees would gather mere blocks from the White House and Capitol. They would also be mere blocks from neighborhoods whose rates of infection rival those of severely-afflicted states in sub-Saharan Africa.

About two weeks ago, the International AIDS Conference wrapped up a week-long gathering of global luminaries in public health and immunology. Much attention was given to the organizers’ choice of location — not only the United States, which hadn’t hosted the conference in 22 years, but its capital city of Washington. Attendees would gather mere blocks from the White House and Capitol. They would also be mere blocks from neighborhoods whose rates of infection rival those of severely-afflicted states in sub-Saharan Africa.

That Washington is a city riven by stark divisions — of class, of race, of opportunity — is a fact sadly beyond dispute. Yet the recent AIDS conference did draw attention to one of the city’s most troubling fault lines — the deadly geography of HIV/AIDS. While Washington’s infection rate for those older than 13 is a frightening 2.7% — by 2007 rates, nearly as high as that of Rwanda — the true and chilling picture lies in the details. While 1.5% of the city’s white residents carry HIV, over three times that amount — 4.7% — of the capital’s African-American plurality test positive for the virus. That rate is, officially, higher than the prevalence of HIV in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, home to a longstanding and appalling epidemic of rape. (Officially — infection rates do not include those who cannot or do not get tested.) It is also a maddening testament to the neglect visited continually upon the poorer corners of Washington.

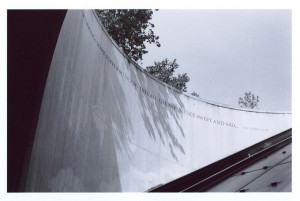

The neglect may enrage or provoke us, and deservedly so, but it shouldn’t overwhelm. Against oblivion the simple act of memory can preserve some small measure of humanity for the ignored victims of the District’s HIV/AIDS crisis. The subject brings me to one of my favorite memorials in Washington, hidden in plain sight but moving all the same. For as long as I’ve lived in the capital, the northern entrance of the Dupont Circle Metro station has stood out among the otherwise drab vistas of the city’s public transit system. A steep escalator carries you down a landscaped slope lined with granite, and through a tall, semi-circular granite face. At the top of the granite wall, just above the bustling surface in one of the city’s poshest neighborhoods, are engraved lines from Walt Whitman’s “The Wound Dresser”:

Thus in silence in dreams’ projections,

Returning, resuming, I thread my way through the hospitals;

The hurt and wounded I pacify with soothing hand,

I sit by the restless all dark night — some are so young;

Some suffer so much — I recall the experience sweet and sad…

The connections are myriad — Whitman famously volunteered in Washington’s hospitals during the Civil War, helping field surgeons and providing simple comforts to those maimed in battle. Nevertheless, the choice of Dupont Circle seems arbitrary, unless we note two facts: first, that the Circle has long been the soul of Washington’s vibrant gay community; and second, that Whitman himself was likely gay. The context heaps another layer of meaning onto the lines, recalling the young and suffering gay men devastated by the AIDS crisis.

Every year, some 8 million people pass through the Dupont Circle metro station, millions passing by Whitman’s granite words. The significance, both historical and contemporary, for the city likely eludes most travelers rushing about town. Yet the confluence of geography, history, and poetry humanizes a stigmatized population and makes visible the hidden suffering of Washington’s HIV/AIDS patients. It is the sort of human touch that has made Walt Whitman America’s most cherished poet and bears witness to a suffering all too near.

This post may contain affiliate links.