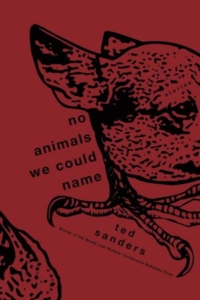

It is sometimes said of a book of fiction that it teaches its reader how to read on its terms. Such books are often reflexive, hintingly aware of what’s happening between reader and text. The stories in Ted Sanders’ varied, fascinating collection, No Animals We Could Name — winner of the 2011 Bakeless Prize, out in July from Graywolf — take on their own such awareness, teaching the reader to read their intricate language.

The opening story, “Obit,” appears as its namesake might in a newspaper, in a 1¾-inch column on the page. From there it splits like a family tree — the boy’s column bifurcates into the woman’s and the man’s — and the reader must choose a way forward into the similetic, image-rich world of Sanders’ fiction. In the left column, Sanders writes that the woman “will die . . . senseless and mute on morphine,” but she “once lay…wishboned around the man, watching a basket-colored sun make urchin shapes through the spruce tree.” Human sex, animal bone, man-made object, celestial body, sea creature, tree. All of these will reoccur in the collection. As will death. To die, in Sanders’ world, is to be drugged senseless; to live is to be drugged by the senses. The drug of sex on a sunny bed: the woman’s “carved arms around her head like a harp’s arms as if the delicate gesture unfolding through them were being sung wordlessly into sight in her face. The woman will survive this understanding.” Whose understanding? Her own? The man’s (he’s doing the looking)? The reader’s? Yes.

Sanders’ project, in “Obit,” and in the book in general, is to engage the questions: what is it possible to understand? How does one trust the physical senses when that other sense, the secret one, the sixth, lurks on the fringe of experience, tempting us away from what’s real? How does one engage the choice to follow a single basket strand but remain mindful of the shape of the whole basket, its beautiful and simple functionality? The answer to all three questions is to trust the strand to return to the familiar weave of memory of the made-up but true. The make-believe, where making’s done by Sanders and believing’s up to us.

The believing’s also up to his characters — mostly American men, women, and children who come into contact with animals, real or imagined. In “Putting the Lizard to Sleep,” a father tries to pass off a sausage in a box as a euthanized pet lizard to his five-year-old son. In “The Lion,” a crippled woman fills a home-sewn stuffed toy lion with the sperm from a sex act she couldn’t feel. The animals in these stories, and, often, by titular association, the stories themselves, become receptacles for bewilderment and distress, for human pain and confusion. In a scene in “Flounder,” a fisherman beats an octopus to death on the deck of a boat while the main character looks on and “thinks how the sound of the bat against the octopus is like a sound he believes he could have imagined, but he understands he has never heard this sound” (emphasis mine). A kind of celebratory regret runs through these stories for the simultaneous adequacy and inadequacy of descriptive language. The sound of bat on octopus becomes, in a recounting to the character’s wife, “[wet] pillows hit by tennis rackets . . . an apple the size of a chair being struck with an ax.” Sanders invites his readers to believe they could have imagined these sounds. In the end imagination will have to do. The boy has to imagine the link is the lizard. The woman imagines the lion to life. And as the man in “Flounder” ends up not with a fish (though he catches one), but with a picture of the fish and a deposit receipt for an account in a fish bank, so the reader ends up with Sanders’ accounts, on these thin sheets, and they’re more than enough.

In places, more than enough can be too much. “Jane,” a ghost-riddle story, is riddled with technical flashiness — the second person point of view begs the question of reader engagement, metaphors stand for description (“heavy hooks of his fingers”), and the last-line simile foists its nice rhythm on a too-common image (“eyes shine in silence like bones in the dark”).

In other places, the descriptions are sharp with sonic impact: “cuff buttons [scuttle] across [a cat carrier],” and lost lizard tails might grow back “lopsided, like soft lobster claws.” And the similes reach just far enough: “tiny cricket turds like thistle seeds,” or jars screwed into lids nailed to the bottom of a shelf “hang . . . like hives. Like stalled drops of water,” or the lion “dragging out a growl like a stick along a fence.”

Sanders seems to always be going for an accuracy, exposing the stories, on the line level, to inaccuracy, but also exposing the relative efficacy of an honest attempt to communicate experience. These moments, these wordy attempts at accuracy, can be understood as thematic adumbrations in their own right. It’s possible, natural, even preferable, to be slightly frustrated by the prose. Sanders is acknowledging, admitting — as he admits in his Acknowledgments — that “life will always be the thing, the story that can’t really be told.”

This post may contain affiliate links.