Can North Korea be beautiful? Should it?

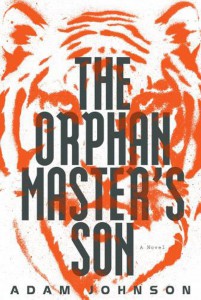

With his new book, The Orphan Master’s Son, Bay Area writer Adam Johnson paints an enveloping, aching portrait of the real-world, alternate-universe that we know as the gulag state of North Korea. At every turn exists a pain and cruelty unimaginable in the day-to-day life of anyone that will ever read this review. Cataloging the slow atrocities makes the book an indisputably masterful piece of terrarium literature; a world that in the first few pages feels imaginary, or cartoonish comes in time to blot out reality. But importantly, it is a world that is more than a curiosity, more than a foil for literature, more than a concept.

Johnson has traveled to the imprisoned half of Korea, and his knowledge of the place and its intricacies seems to shine through. The loudspeakers blaring propaganda in every home, the orphans picked off the street to die working. The smallest details of life in the choking state are told by way of flowing, romantic, and familiar structures of love, loss, and coming of age. They come mellifluously, poetically; the familiar language of the wordsmith MFA grad transposed to stand for unspeakable evil: famine, concentration camps, and omnipresent control. Johnson’s writing is largely without fault, his characters yearning and fleshed, his plot suspenseful, his sentences immaculate. But the setting remains a curiosity, a useful substrate and little else.

In this country we know little about North Korea: a vague sense of a pitiful, hungry, forsaken place run by delusional little men. In the end, not unlike our understanding of many corners of the globe. The theatricality of the recently deceased Kim Jong-Il became a particular sort of punchline, whether through collections of images of the dictator looking at things, or in the “I’m So Ronery” persona developed in Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s Team America. Considering that something like three to four percent of his nation was starving to death annually in the Nineties, the jokes lose a bit of their humor.

But then little can stand up to the horrors of complete repression and terminal deprivation. Learning to live (and fight) in the darkness of an infiltration tunnel, scooping the frozen-off toes from a replacement boot on entrance to a forced-labor camp: these are the haunting episodes that make up a powerful novel and The Orphan Master’s Son is beautiful, heart-breaking fiction. But to write of things that some would call genocide as, “the slow endless pitch of everything to come,” is just too lovely, too contemporary, too literary. So much of Johnson’s language feels as if it could slot into any time, any place. If only for a few hundred pages, there is more justice to be done than Johnson’s novel attempts, more gravity to be lent in glimpsing a suffering that simply will not end when this book’s cover is shut.

This post may contain affiliate links.