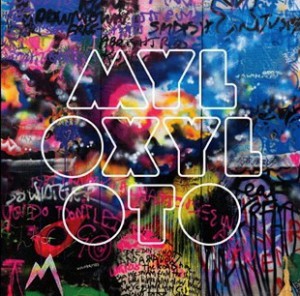

No strangers to bold reintroductions, Radiohead’s quest to debunk themselves — and presumably all of pop music — takes its sharpest turn at Mylo Xyloto‘s 44-second mark. What begins as a soft mash of xylophones, synth, and keyboards ends as a jarring, pop-spattered crescendo that threatens to change everything we knew about the band.

No strangers to bold reintroductions, Radiohead’s quest to debunk themselves — and presumably all of pop music — takes its sharpest turn at Mylo Xyloto‘s 44-second mark. What begins as a soft mash of xylophones, synth, and keyboards ends as a jarring, pop-spattered crescendo that threatens to change everything we knew about the band.

It comes as no surprise. We’ve seen this before, with “Planet Telex” on The Bends, “Airbag” on OK Computer, “Everything in Its Right Place” on Kid A, and “2+2=5” on Hail to the Thief serving as album-defining — and at the time, genre-shattering — launchpads for a new sound.

To obliterate everything that worked on the last album is to be Radiohead. Never bound to the limitations of success, Yorke and Co. have long been in possession of creativity’s deep secret: memories are best created by forgetting them.

Let’s for a second then forget that the aforementioned crescendo immediately leads into “Hurts Like Heaven”, a Listztomania-esque Billboard-friendly hit that features an Auto-Tuned Thom Yorke, and a chorus that goes, “Oh you, you use your heart as a weapon, and it hurts like heaven.” Let’s forget that between Yorke’s giddy caterwaul, and Jonny Greenwood’s most syrupy guitar work to date, there is enough schmaltz on this one song to last for a band’s entire catalog.

Yes, the average Radiohead fan is going to wince — if not curl up into a ball entirely — upon the first several listens to this album. Mylo Xyloto doesn’t merely defy the boundaries of the classical pop album; it has become the definitive expression of the post-pop album.

It does not relent. From the opening salvo onward, you get the feeling that the band’s entire discography is under siege. The lush mid-range tones so abundant on past albums have been drastically recessed. The resulting expanse leaves Yorke more vulnerable than ever, his vocals hung out to dry in an echoless void. A canyon of sound surrounds him, cracking in all the right places.

The scene is scored by Jonny Greenwood and Ed O’Brien’s twinkling trembling guitars. Both guitarists are having fun again, certifiably rocking out on all three singles: “Paradise”, “Princess of China”, and “Every Teardrop is a Waterfall”. The last is a euphoric post-pop anthem, propelled by Greenwood’s rapturous, bagpipe-like guitar chimes. O’Brien stars on “Major Minus” which closes with his most hard-hitting guitar solo since OK Computer. Throughout the album, both guitarists revert back to Edge-like, major-key riffs, which amplify its blissful tonality. Phil Selway’s drums and Colin Greenwood’s bass, while sparser and more understated than on past albums, push Mylo along with a delicate pulse.

Credit much of the band’s transfiguration to newly appointed producer Brian Eno. Legendary for his work with U2 and Talking Heads, Eno too has made a career out of shifting a band’s sound. Achtung Baby saw Eno update U2 with elements of industrial and electronic dance music, and Remain in Light remains noteworthy for Eno’s fusion of new-wave and African polyrhythms. But it was the blend of musical innovation and pop accessibility on both albums that proved to be Eno’s biggest coup.

To achieve the same measure of success on Mylo Xyloto, Eno borrows from the most unlikely of sources — himself. From the throb of dubstep on “Up in Flames”, to the flickering witch house synth of “Charlie Brown”, to the Rihanna-assisted chillwave banger, “Princess of China”, Mylo plunders several subgenres of industrial music that Eno himself indirectly pioneered years ago. Underneath lies a ghostly meta-album that exploits the tension between space and time. But in the foreground, it’s Radiohead’s own resurrection that steals the show.

For a decade and a half, a significant corner of Radiohead’s fanbase has longed for a return to the anthemic splendor of Pablo Honey and The Bends. The mid-’90s saw Radiohead lumped with many of rock’s biggest acts — Nirvana, U2, for starters. Radiohead, like so many of those bands, aimed for the back of the arena, ensuring they would be heard. It took a massive shift in tone, guided by longtime producer Nigel Godrich on OK Computer, for the band to realize that fans would still listen — and, in fact, listen more intently — when their aim fell short, when they whispered instead of shouted. How fitting then that “Stop Whispering”, “Anyone Can Play Guitar”, and “Blow Out” would be among Pablo Honey‘s track titles, as Kid A‘s “How to Disappear Completely” would aptly convey their later, more minimized sound.

Under Godrich, Radiohead spent the time between records chiseling away at their sonic identity. Each subsequent release uncovered new layers of isolation, a reflection of the widening divide between the band and the rest of pop music. Aliens, car crashes, memory loss, death, ghosts — these images of departure haunted each release from OK Computer to this year’s The King of Limbs. Just as Radiohead seemed poised to float away from themselves entirely, they crash back to Earth on Mylo Xyloto.

Finally delivering on their early promise to be one of rock’s biggest bands, Radiohead has done so while remaining one of rock’s best. Mylo‘s strengths lie in its ability to weave the intricacies of their current sound with the simplicity of their older sound. The line between past and present is ultimately blurred, and the resulting haze seems to lead Radiohead closer to themselves — done with experimenting with their music, and more concerned with enjoying it.

This post may contain affiliate links.