The Full Stop blog is a strange beast. It can take the highest of roads, discussing literature and art and philosophy, while also going fairly astray, trying to divine the true identity of the devil (the answer is below) and gauge the prospects of intergalactic travel. In 2015, it published pieces on The Offspring and suicide, dinosaurs and apocalypse, and why a guide to quitting smoking might be one of literature’s greatest works. The blog is beastly in its scope and strange in that even the editors never really know what type of content the coming year (or month, or week) will bring. Still, we love this furry little monster and couldn’t imagine not having a section of the site for the pieces that come straight from the heart.

So beat right along with us, and, if you can, give a little money to help us keep going.

Tie Your Own Rope — Kyle Boelte, January 13

One of the most important albums of my life is the album I spent almost twenty years not listening to. The others, the ones I listened to daily, over and over again for years, the ones I memorized, they stay with me too — even after the breakups or the new relationships or the new cities that somehow sapped the old music of some of its former power. Each album can take me to a specific place, a time, a face staring back at me — or the back of that same person’s head as they walk away. But this album, Smash — I spent years turning the radio dial when one of its songs came on. I could never escape it.

The True Nature of The 52 Places to Go in 2015 — William Harris, February 24

How has the NYT compiled the list? My theory is they’ve clumped their travel page staffers into groups, likely with internal hierarchical ordering systems, and given each a focus. The first group surveys the geopolitical situation. Which countries, previously shuttered to the world, or at least Americans, are now open for business? Cuba rises to number 2, due to proximity, allure, and our nostalgia for their cars; Zimbabwe falls in place because they have trimmed their currency of its infamous and flabby zeroes. An important line of thinking for the geopolitical specialists is finding the countries we normally like that have entered periods of crisis. Once one is pinpointed, the group scans the region for who is capitalizing by offering identical luxuries in safer, less conflict saturated terrain. Ethnic strife in Kenya might ruin a safari, but Tanzania has nice lodges, too. Kos, the Greek island, “is out,” because oppressive debt hasn’t worked in our favor by making Greece cheap, but Kaş, a quiet place I once went to on the Turkish riviera, “is in.” It’s in the southwest of Turkey, not at all close to Syria.

No GrAttitude: Peter Tunney Is the Devil — Max Rivlin-Nadler, April 14

The bar for public art is fairly low. Communities seem far more excited to have relieved a space from the vice-like grip of commercialism than actually following through with making sure that the art is any good. This is a serious flaw in public art, and one that even has the ability to make even the most ardent leftist turn their back on the very idea of it. Most ads have some sort of coherence, a viable message to parse — we know why they’re so bad. Public art just ends up being mostly underwhelming, and for the most part, that’s fine. It’s nice to think of the possibilities now that the space has been liberated. Which is why the work of Peter Tunney is so incredibly offensive to any sane person’s sensibilities. It’s ugly. It makes no sense. And it will (rightfully) turn many people off of the entire idea of public art. Death to Peter Tunney.

Roger Shawyer’s EmDrive — Silvia Mollicchi, June 24

There will be no engineering magic, no smell or background motor noise. A lack of inner material logic will delude desires for black-boxy mechanisms and scientific romance: just a metallic cylinder, cutting out a round slice of universe with its hollow shape. And also no fluid, no leaking propellant and no endless wars over natural resources — or visionaries losing their sight to save intergalactic economies, for that matter. The relationships we entertain with propellant substances are unique. The inner secular workings necessary to amalgamate them, the slow accumulation of carbon fossils, and then the velocity with which we burn them away constitute the traits of now familiar characters. All that generative narrative would be gone.

The Matter at Hand — Andrew Mitchell Davenport, June 25

The reality of American life is no doubt stranger than fiction, and there aren’t enough writers to exhaust the plot possibilities latent in our nation. I spent my spring and early summer reading Ellison, preparing my history classes for our studies of the Civil War, but the news inevitably barged in on my attentions. We stayed up late watching the television, and in the morning the papers reported the riots in Baltimore, the killings across the States, and somehow, inevitably, my life trudged on amidst the furor. I read and thought about writing, but there never seemed to be enough time. There are certain events you can never gain perspective from.

The Poetry of Pedestrians— Dustin Illingworth, July 15

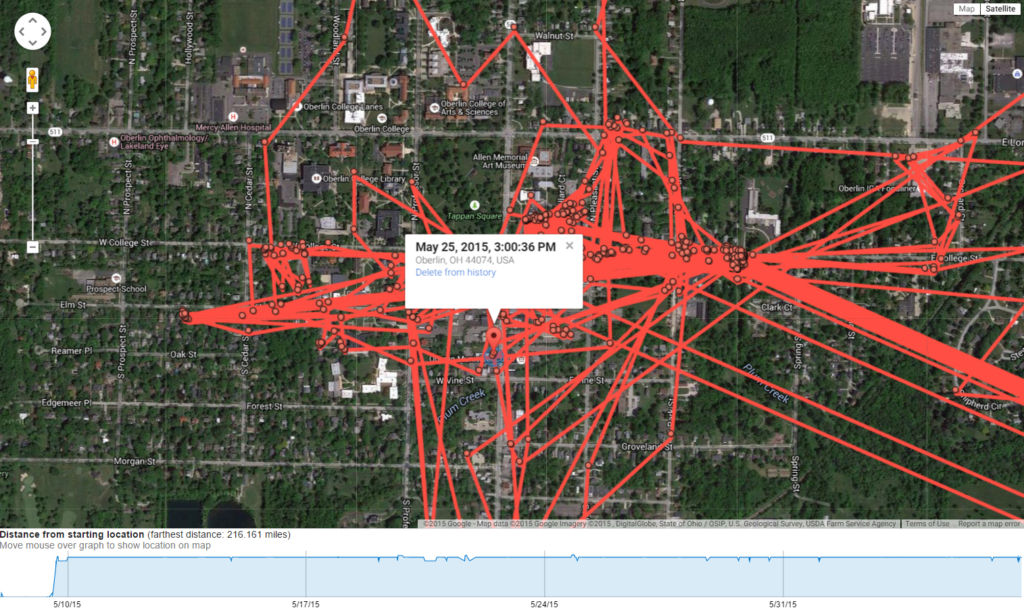

There’s something charmingly twentieth century about the dérive, of a piece with Surrealist Exquisite Corpse and Jarry’s ‘Pataphysical work. Never before or since have games been integrated into intellectual and aesthetic action with such disruptive intent. And though we may be a long way removed from the roiling midcentury moment when art seemed like it might reshape the world, I believe there is still much remaining in the dormant practice of the dérive to rattle and instigate in 2015. A new kind of dérivist is needed, one aware of both the implicit organization of space as a funnel to consumption, and the more recent development Debord probably couldn’t have imagined in 1955: that of infinite surveillance, tracked movement repackaged as data currency, and a disturbingly effective brand of predictive analytics.

The End of the Jurassic World Is Nigh — Sam Kriss, July 28

It might not mean anything in this vast, flat, and indifferent field, but the most successful movie sequel of all time looks to be this year’s blockbuster Jurassic World. Perhaps for good reason. In a surge of blood and fury, Jurassic World marks the moment when the sequel-industrial complex gained sentience. Of course, another sequel’s already been announced, and so the meaning of this film will probably be snuffed out before long. But for one opening weekend, the culture revealed itself for what it really is: a roaring, deadly monstrosity, full of pain, fury, and suicide.

How to Exploit a Dead Writer — Tom LeClair, August 12

I could countenance the exploitive and inauthentic qualities of The End of the Tour if I thought that it would do more than enrich all those involved in its making, that it would cause those who had not read Wallace to examine his work. Copies of his books are stacked in the bedroom where Lipsky-Eisenberg sleeps, but I find it hard to imagine many of the uninitiated in the audience running to grab them because the Wallace of the movie isn’t all that brilliant or profound or even very amusing. He signs copies of Infinite Jest but is never given a chance to read aloud from it, perhaps because the novel’s language would have demonstrated how impoverished this movie’s cinematic language is.

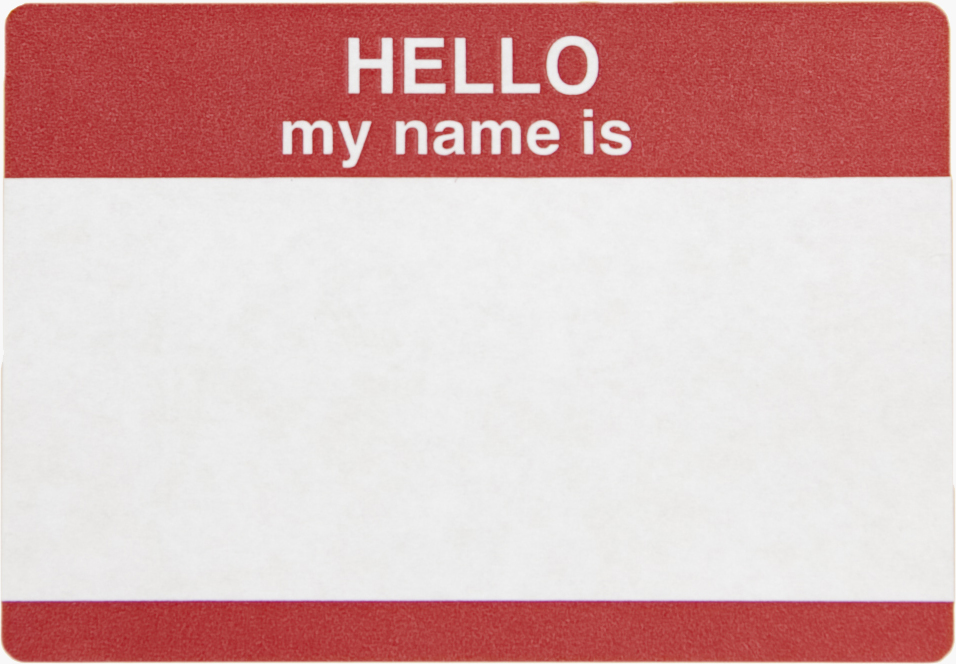

A Brief History of Name Fuckery — Larissa Pham, September 10

Names have power. I don’t feel close enough to my Vietnamese names to use them. That’s a privilege that was stripped from me in many ways many years ago and I don’t think I’ll ever regain it. I don’t trust people to be able to pronounce them, to understand what they mean (and to not ask what they mean, which I’ve always thought is a silly question, as though American names don’t have meanings too). I don’t trust people to not exoticize me by proxy, to think of me as all this or all that when my identity is fractured and divided. I don’t trust people to not make a mockery of my names. I keep them hidden. I have enough to deal with as it is.

My Two Favorite Books — Sasha Chapin, September 29

People like to wonder about what literature is good for. This is a stupid, easy question. It’s more relaxing than Twitter. It makes you better at words, which makes you better at remembering things, and also better at e-mail. It also might just be a privately enchanting thing you can do without hurting people. But I suspect that people who ask this question are looking for more serious answers, which is to say, more complex and less easily defensible answers.

One serious answer is that literature can make you a better person. If we accept this, accept the possibility that literature improves our souls—if that is, maybe, how we distinguish good literature—then my personal nomination for the greatest work of literature of the 20th century is Allen Carr’s The EasyWay to Stop Smoking, followed immediately thereafter by James Joyce’s Ulysses. I believe that these books offer a certain reader the chance to become a significantly more compassionate person. That’s because I think the root of compassion is realizing that however smart you think you are, you might be less smart than that.

The Disgraceful Materialisms of Joanna Ruocco — Caren Beilin, October 6

I read this novel in search of what I love in Ruocco’s writing, this movement of the material, and I marveled at its failure to surface from holes so buttoned up in Dan/Dan. When these movements do surface, they float utterly briefly, fantastically, before yet another public problem, problem of being “woman,” that public term, that problem — but Melba is always waiting to perceive something, and what I ended up marveling at is Ruocco’s deftness in interrupting herself in service of this chipper, despairing performance. It is a novel of brief floods of material perception, despairing technic of those busy being fucked.

Like Cattle Towards Glow — John Farley, October 28

These are bodies at the moment of encounter with crisis, and there is a kind of saintliness to their response. Even to death and in their assholes. That this humanistic tension is so palpable owes to the strong structural constraints placed upon the bodies, despite, and in interesting contradiction with, the film’s apparent resistance to linearity. It lends to these vignettes an impression that the confusion of these bodies is our own. When the junkie kid fists the kid who says he’s going to die anyway, the viewer gets the impression that both are submitting to some other fist that’s huge and abstract.

Nets — Hestia Peppe, December 15

I’m typing because I can just about afford to. Text is the art form with the smallest overheads and this screen is the only space I can hold. The houses I can see from my window increase in value as I stare at them; they earn more than I do at my day job. Back here in London, the net I’ve strung is so thin that I can always see the bad maths of austerity and housing crises and neoliberal financial structures showing through — the drop below.

This post may contain affiliate links.