This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

You can never escape apocalypse. You might not perish in it, but you must pass through it. If there is a law that governs the wild, oneiric universe of Mircea Cărtărescu, arguably the world’s greatest living novelist of the surreal, it is this.

Solenoid, Cărtărescu’s most recently translated novel, ends by destroying the place with which he is most closely identified—Bucharest—where he grew up and, to this day, resides. Bucharest, city of dilapidated ruins and dentist chairs, bursting chrysalises and sublime terrors, breaks off from the earth and ascends into the heavens, leaving a giant abyss behind. Glimpsing the underside of the city, the narrator can finally see “the horrifying sack of hell our pain had fed.” He turns away from these “legions of parasitical demons, like Trichenella larvae, feeding on our interior life” and heads off into the woods with his partner and their child to begin a new life in an abandoned church.

This is not the first time Cărtărescu has destroyed the world he has imagined. Bucharest had suffered cosmic obliteration (and regeneration) in “The Architect,” a story that closed his first novel, Nostalgia. It was bombed out in Blinding, such that one area of the city is all rubble except for a lone elevator shaft that rises toward the heavens, before ultimately becoming, with all the world, razed by the purifying fire of pure recollection, “digitizing our blood and our tendons and our nerves, transforming them into memory, pure memory, holographic, indestructible.” And then, in Solenoid, the city is ripped from its foundations and raptured into the sky.

Apocalypse might be what it means to wake up from dreams, or to close, for the last time, a book. Apocalypse might be the name for the self’s end, or the dissolution of the world into memory. It is always, at least, the end of the translated fiction of Cărtărescu—Nostalgia translated by Julian Semillian in 2005, Blinding, ushered into English in 2013 by Sean Cotter, and Solenoid in 2022, also translated by Cotter. Like stone lions flanking the gateway to a fortress, apocalypse stands before Cărtărescu’s transmutation of world into fiction—and the moment when the text of that fiction arrives at its final line.

*

These apocalypses only affirm the messianic election that suffuses Cărtărescu’s writing. Nostalgia, a novel made up of five short stories that refract each other, features a roulette player “whose life is an actual mathematical proof of an order in which no believes today,” a Jesus child who entrances his fellow kids with stories of the order of the universe before they pelt him with balls of earth until he falls into a seizure, a dreamer who can unlock the great archive of dreams called “REM,” and an architect whose music, played out of a Dacia car, remakes the universe. Blinding’s sprawling narrative coalesces around the “piercing sense of predestination” experienced by its narrator, Mircea, telling the life of his mother and ranging from Bucharest to New Orleans to make sense of his existence. As one character in the novel proclaims, “Every birth creates a religion.” The unnamed narrator of Solenoid is also chosen, but by himself, in a kind of spectacular desire to create reality anew:

Something is happening to me, within me . . . the text that, as I read those sophisticated and powerful and smart and coherent books, full of madness and wisdom, I always imagined and never found anywhere: a text outside the museum of literature, a real door scrawled onto the air, one I hope will let me truly escape my own cranium.

It is only later that he realizes the six solenoids plotted across the city are indeed entrances into other scales of experience.

The worlds Cărtărescu describes are not idyllic. The phantasmagoria can verge on the gross and gruesome. But its characters are never without a kind of sense of the cosmos bending toward them. This otherworldly presence extends even to Why We Love Women, a collection of occasional pieces that Cărtărescu wrote for Romania’s Elle and other magazines, which shines a spotlight on each person he mentions. For a moment, at least, each character seems to occupy the center of Cărtărescu’s stage. Every character knows they are part of a greater text; as the woman who gives birth to a giant butterfly in Blinding reflects on her existence: “how odd, to live through someone else’s history, as though you were entirely a dream creature, created by the mind and yet complete.”

The maximalism of Cărtărescu’s dream world has challenged anglophone readers since Nostalgia was first translated in 2005. Then, Kirkus Reviews suggested his work was inaccessible, warning that even its layout presented a barrier: “Long blocks of prose with minimal breaks make it hard to enter.” Publisher’s Weekly mischaracterized the refractory novel as “a collection of five unconnected stories,” and proved unable to appreciate its baroque style, proclaiming, “The book, extracted from its cultural context, loses much of its power.”When Blinding arrived in 2013, which Boyd Tonkin heralded in London’s The Independent as the announcement of Cârtârescu’s candidacy for a Nobel Prize in Literature, most US publications ignored it. It was left to the Kenyon Review and Los Angeles Review of Books to acknowledge how “Blinding creates an entire world from dreams, memories, visions, and chimeras, where statues move and have memories and dreams.”

The significance of this world, though, has left some reviewers baffled. Even as The London Review of Books was amazed by Blinding, it couldn’t quite place this world:

It’s as though Cărtărescu has chosen to withdraw from any topical literary or cultural conversation, and that rather than attempting to stitch together a fragmented contemporary reality, he is returning to a time that never actually existed, an imaginary time when all genres were one genre and all discourses one discourse, before everything broke into parts.

In one of the few major publications to pay attention to Cârtârescu’s Nostalgia, Thomas McGonigle suggested an anthropological approach to Cârtârescu’s writing in the Los Angeles Times, finding it provided “the clearest approximation of the interior lives of those living in that city through the darkest days of the Ceausescu regime.” More recently, some critics have framed Cărtărescu’s world as a reaction to the fall of communism, suggesting that his play with time is a way of responding to this “trauma.”

Yet, rather than looking beyond his texts to national history, what might it mean to reckon with this world as an experience in its own right? Alta Ifland’s review of Solenoid, one of several illuminating engagements with this most recent novel, points to the contradictions and complexity of literary space, which can contemplate, and even seemingly advocate for, its non-existence. “Of course, the reader can say that the very existence of this book contradicts the narrator’s/author’s claim about his lack of interest in a literary project,” she writes, “but this is the paradox and advantage of literary space, which is also that of a dream: to allow the writer/dreamer to speak about it while being inside it, to be both inside and outside of a given space.”

*

“The subject of this book,” writes Georges Perec in Species of Spaces, “is not the void exactly, but rather what there is round about or inside it.” This statement might not be an untrue characterization of Cărtărescu’s own oeuvre, which is written also out of a sense of the nothing that could easily be present instead of something—an understanding that reflects the surrealist tradition on which they both draw. “We live in space, in these spaces, these towns, this countryside, these corridors, these parks,” Perec notes. “That seems obvious to us. Perhaps indeed it should be obvious. But it isn’t obvious, not just a matter of course. It’s real, obviously, and as a consequence most likely rational. We can touch. We can even allow ourselves to dream.” Dreaming allows us to remake space, without disturbing it: “There’s nothing, for example, to stop us from imagining things that are neither towns nor countryside (nor suburbs), or Metro corridors that are at the same time public parks.” Writing becomes a kind of dreaming that leaves behind its traces as a spatialized marking on the page. “I write,” declares Perec, “I inhabit my sheet of paper, I invest it, I travel across it.” By traversing the space of the page, Perec conjures a whole new reality, whose existence is only on the page, an entire universe mapped out in fifty-four square inches, the page, a cartography of an imaginary:

This is how space begins, with words only, signs traced on the blank page. To describe space: to name it, to trace it, like those portolano-makers who saturated the coastlines with the names of harbors, the names of capes, the names of inlets, until in the end the land was only separated from the sea by a continuous ribbon of text. Is the aleph, that place in Borges from which the entire world is visible simultaneously, anything other than an alphabet?

And yet, the line ends, the void begins. Where the alphabet means everything, the whiteness of the page signifies nothing. The end of the world is always waiting beyond that last character.

*

Cărtărescu is often compared to Jorge Luis Borges due to the heady, referential intricacy of his fictions—and he has readily acknowledged his debt to the blind librarian. But again and again, when given the chance, he has named his great literary idol as Franz Kafka. Cărtărescu still writes out by hand every word of his novels, beginning at the beginning and ending at the end, claiming no revisions. This manner of composition aspires to that of Kafka, who wrote everything in his notebooks. For Cărtărescu, this represents an ideal melding of art and life—no space demarcated for the literary, but a refusal of that division. “Everything that he did was a single manuscript!” Cărtărescu has said. “He wrote a very long manuscript, including his novels, including his short stories, including his parables and so on, and integrating everything into his journal, his diary.”

Cărtărescu also roots his writing in his journal, which he calls the “origin” of all his work, the vine of his fiction: the “fruit.” He has kept a diary religiously since he was seventeen. As he explained in a 2018 interview, “I feel I have never really lived my life, but have constructed it, changed it in all kinds of anamorphic ways, invented and re-invented it.” After all, his fiction insists that memory and invention are one and the same. “I remember, that is, I invent,” he writes in Blinding.

Mircea Cărtărescu was born on June 1, 1956, a Gemini—like Dante, Yeats, and Bocaccio before him. A child of working-class parents, he grew up on the outskirts of Bucharest. In and out of the hospital as a child, he eschewed the soccer pitch as a teenager and instead read for eight hours a day, which prepared him to become part of the literary underground known as the Blue Jeans Generation, the Romanian writers drinking deep from US texts—highly influenced by the Beats.

Cărtărescu achieved literary success and notoriety in what seems a single coup at the age of twenty-one. With his first poetry reading before the “Monday Literary Circle,” a poetry circle under Nicolae Manolescu, he received acclaim and membership in this group until it the state forcibly dissolved it in 1983. After graduating from Bucharest University in 1980, he spent the final decade of the Ceausescu regime as a schoolteacher and poet. He became a published novelist in 1989 with the publication of The Dream, an expurgated version of Nostalgia (1993), and a professor at Bucharest University once the dictatorship ended. After his 1990 publication of Levantul (The Levant), a parodic novel in verse, he turned his attentions wholly to prose, which has brought him international renown. Though there is so much of his work yet to make its way into English, his work has now been translated into twenty languages—and he has won prizes across the world, most recently the 2022 Guadalajara Book Fair’s FIL Prize for Literature in Romance Languages.

His life refracts across his literature. Andrei, the narrator of “The Twins” in Nostalgia is also a Gemini. His stays in infirmaries as a child become settings in Blinding and Solenoid. His narrators frequently are journaling, as Cărtărescu is known to do; Solenoid, for example, is explicitly the writing of a set of diaries. Indeed, the narrator of Solenoid, refers to Cărtărescu as a figure whom he could have otherwise been, a man who “keeps writing, keeps tattooing the skin of his books.” “His books remain inside,” the narrator writes, “they are inoffensive and decorative, they make the prison more palatable, the mattress softer, the pot cleaner, the guard more human, the axe sharper and heavier.” This kind of commentary reminds us about what, in part, Cărtărescu so admires in Kafka, “a writer who doesn’t play the game, who writes only for himself, who writes not for the readers but for God.” Kafka wanted to put all his work to the flame.

*

His fictions speak as if from the edge of the void. Cărtărescu’s first story to enter the English language is bracketed by citations from T.S. Eliot’s “The Song of Simeon”: “Grant Israel’s consolation / To the one who has eighty years and no-tomorrow.” This opening story of Nostalgia, “The Roulette Player,” is recounted by an old man in his armchair, “a bundle of rags and cartilage,” an exhausted, failed writer who, like the line from William Butler Yeats’s “The Circus Animals’ Desertion,” which his self-description recalls, “sought a theme and sought for it in vain.” The story of the roulette player’s terrible luck is “his coffin and cross of words.” He can only be saved from the void by his readers, who resurrect him.

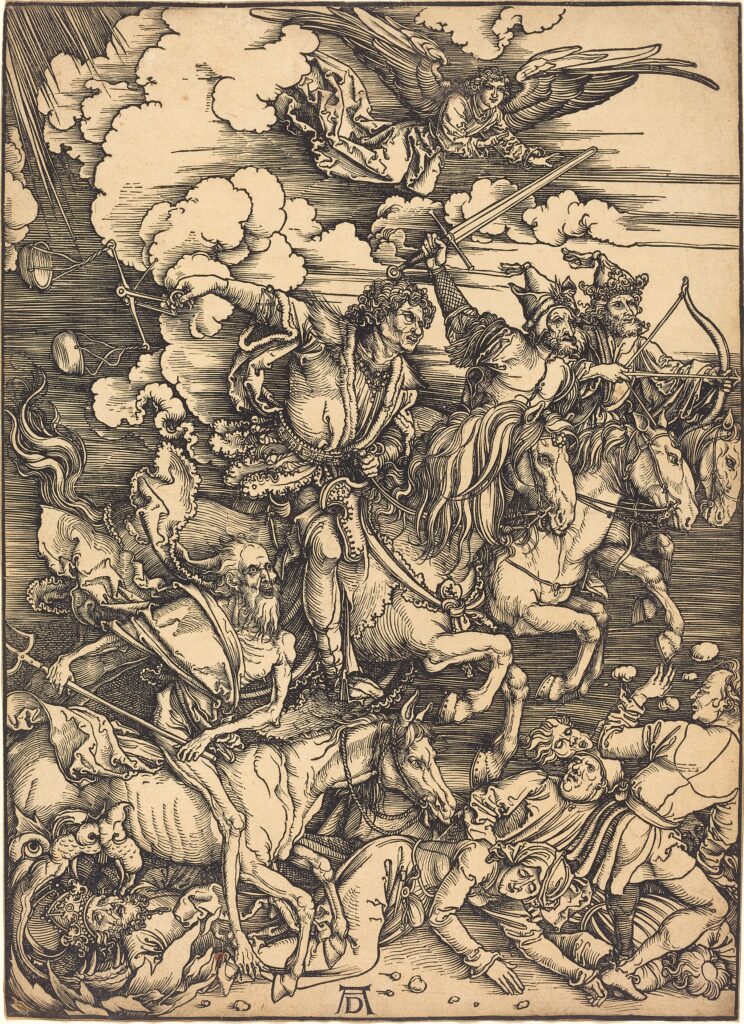

This resistance to the anonymity of death becomes incarnated as the group of the Picketists in Solenoid, a group that comes together at morgues and hospitals to protest the indignities of the human condition. Following the model of Dylan Thomas’s poetry, they proclaim “Cry the tears of Xerxes rage, rage against the dying of the light.” And yet, they gain no satisfaction. Their leader, a Virgil who is not fated to guide anyone through other realms, is squashed “like a bug” by a “gigantic statute of Damnation.”

Yet, even without hope of resurrection through reading, Cărtărescu’s characters continue to write. In “The Twins,” which discloses a love affair so intense that the lovers exchange bodies and, when the affair ends, commit suicide, fire is to reduce the manuscript to ash. Is writing a way of extending his life, the narrator (who now inhabits the body of Gina) asks: “Why am I continuing to write these lines, if I know that I will destroy everything? Why am I composing, look, one letter, and then, again, another?”

Perhaps the most famous literary instance of the tattoo is Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony,” where the law inscribes its broken code into the transgressor’s flesh—a form of capital punishment. Yet, for all Cărtărescu’s idolization of Kafka, tattooing is a poetic rather than penal act in his novels. It is no representative of law’s subjugation of human beings, but rather the manifestation of the universe’s unfurling into surreal poetry.

In “REM,” the shifting tattoos of a man who measures “two meters forty-eight” disclose the future. It is among these images “that only dreams could bring,” that the idea of REM appeared: “a kind of a kaleidoscope in which you can read all at once the entire universe, with all of the details of each moment of its development, from genesis to apocalypse.”

In Blinding, it is a tattoo that contains the universe. Hidden under the hair of Anca, the narrator’s neighbor, it reveals to the narrator that he is chosen:

There, on Anca’s skull, Herman (the same one I had talked to for hours on the cement steps of the block on Stefan cel Mare, listening to his husky whispers about Felicia and the cosmos and his need to drink two bottles of vodka per day) had tattooed Everything, and everything had my face.

Mircea stares at this tattoo and, when he has finished gazing upon it, does not know if he became lost within it. The tattoo becomes a kind of religious scripture that shapes his world.

And, where the tattoo is a text, the experience of writing is a kind of self-tattooing. In Solenoid, the narrator explains his writing by resorting to tattoos. “I had poems written with a needle on the whites of my eyes and poems scrawled over my forehead,” says the narrator of Solenoid. “I was blue from head to toe, I stank of ink the way others stink of tobacco.”

This metaphysical tattoo of infinity recurs in Solenoid. “I sometimes fantasize,” the narrator recounts, “that I was once, in dream or another life, a tattoo master, so abstruse and so pure that no one ever had access to my art’s wonders of lace, ink, and pain. Shut in my room, alone in front of the mirror, I covered my skin with mute, crooked, overlapping, unreal arabesques, like the Nazca lines and the suppurating networks produced by mange.” In this fantasy, the narrator tattoos all of his physical body. It provokes a crisis. “What would my life be without my sole source of meaning and happiness?” he wonders. “It took me years to peel the idea of tattooing away from the idea of skin.” He tattoos all of his internal organs—and beyond:

I moved toward the border between body and spirit, I crossed it, holding my instrument of torture, and I began to tattoo myself, knowing I would never exhaust, even if I spent eternity wounding, the infinity and infinitely stratified and infinitely glorious and infinitely demented citadel of my mind.

Cărtărescu’s universe can not only unfurl on the skin but also live within it. Where Cărtărescu describes a tattoo as “mange,” the designs on the skin of Solenoid’s librarian are, indeed, the thin trails of insect life. This character provided the narrator with the books he read as a child, seeding the imagination and actions of his life that led him to ultimately re-encounter the librarian, who possesses a rare copy of the gnomic fifteenth-century Voynich manuscript. However, even more precious is the “rabies colony,” which the librarian has cultivated on his flesh and blood, becoming a life-giving God to these insects. He delivers to the narrator a task that the narrator agrees to bear—the message of salvation, that these creatures are cared for by the benevolent force that is their world. Through the mystical power of a solenoid, the narrator transforms himself into a mite and enters this colony. He goes on a mission to “discover, even if I had only a slim chance, whether salvation was possible. If the message could pass from our spiral to another.”

This experience literalizes the metaphor to which Cărtărescu returns, again and again, echoing Kafka—the insect-like life of humans. Could it be, that as humans are to bugs, humans are to other intellects? This journey is an attempt to consider whether it is impossible to transmit messages across such distinct scales of experience—a problem that seems to present a deep pessimism about the very venture of literature. “I saw how everything was misinterpreted, retranslated,” the narrator writes, “not from one language to another, but from one world to another, until love became yivringzrw and belief became sumnmnmao.” He is ultimately martyred, his eight legs devoured by the creatures who responded with fear when he was sent only to tell them about the love of their world. When he reemerges from his time as a mite, the librarian looks at him: “His eyes were full of tears, they also held an enormous question, perhaps the greatest question that our cerebral ganglion can ask. In response, making an almost imperceptible motion with my head, I said no.”

*

Throughout Solenoid, the narrator and his lover, Irina, ask each other a question. “What would you do if you could save one thing only from a burning building, and you had to choose between a famous painting and a newborn child?” He insists he would save the child, even if told that the child would become Hitler. In her review, Ifland offers a criticism of Cărtărescu’s insistence on privileging art over life. “There were moments when I felt that Cărtărescu’s programmatic rejection of literature in the name of life (his choice of the child over the masterpiece) was a little self-indulgent,” she writes, “insofar as, logically, this book wouldn’t exist if he truly rejected literature.” Yet, within Cărtărescu’s world, art that has become fixed and bound is already dead—ornamental. Real literature needs to be written on flesh.

Across Cărtărescu’s oeuvre, figures recur who express this desire, as in “REM” the character of Egor, who knows that he will never express what he calls “the All,” but spends every day writing:

I dream incessantly of a creator, who through his art, can actually influence the life of all beings, and then the life of the entire universe, to the most distant stars, to the end of space and time. And then to substitute himself for the Universe, to become the word itself. Only in such a way can a man, as an artist, fulfill his purpose. The rest is literature, a collection of tricks.

This creator is imagined in “The Architect,” an architect who becomes obsessed with making music in an organ installed in the dashboard of his Dacia. In this story, the architect’s sonic creations become not only an object of worldwide reverence, but, ultimately, the celestial music of the stars, playing on as the universe contracts and explodes in new glory.

At the end of Solenoid, the narrator records how he destroys the manuscript that makes up the novel, relinquishing it to the goddess of Damnation. She possesses the power to allow him to escape his reality, which has been his greatest wish up to this point. However, rather than sacrifice his child and leave this world, he chooses, instead, to give up his literary creation. He chooses to remain in his reality, a sacrifice and commitment that, for the first time in the text, bequeaths him a kind of begrudging contentment, a sense he “truly had a life.” “And now,” he writes, “in a few moments, I will set these last pages on fire over the chasm. I will watch the feathers of ash descend, in wide spirals, toward its unsoundable depth.”

This text shall diegetically return to the void as reader and writer both too must turn to confront it, which waits for them after the text’s final line. This final act affirms the narrator’s commitment to a kind of Kafkian writing for no one. And, yet, when the text becomes “feathers of ash,” it has already written itself through and out of the flesh of this narrator. And, indeed, the manuscript that the narrator will burn has already been read. For both narrator and reader, the manuscript to be burnt has already been reduced to the husk of what it once was—brimming with all sorts of unknown possibilities. They have already both read it before its destruction.

Readers here occupy both the position of the divine fire that consumes the text and the parasites that the narrator sees on the underside of his city, drawing vitality from his internal life. This instability heralds the instability to come when the reader must go beyond the novel—enter into the world beyond its characters. The reader’s confrontation of the apocalypse is a reflection of the one the writer also had to face, not only within the text, but also Cărtărescu’s own composition of this novel. There is a moment when he must cease writing—which does signify a break in his own life. He must give up a project that has been the center of his life—and return to the reality outside of it. So too reader and writer come to the end of these 675 pages and each has to then leave its world and go into the unknown beyond “END.”

The apocalyptic end marks a break. The novel becomes prayer, a burnt offering of an entire world that has ended and yet heralds a new existence that is not for it to imagine.

Sanders Isaac Bernstein is a writer living in Berlin. His work has been published in Jewish Currents, Hypocrite Reader, and newyorker.com, among other places.

This post may contain affiliate links.