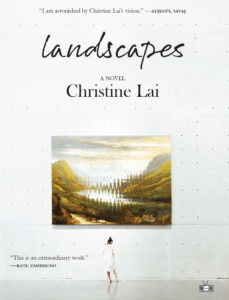

[Two Dollar Radio; 2023]

“I picture myself in the midst of a ruin,” Penny writes for the first entry in her diary, opening Christine Lai’s Landscapes, a speculative Gothic novel set in a near future England drastically altered by climate change. A rich meditation on the burden of remembrance, the ruins of the past, and the ruins that climate crisis will soon bring us, Landscapes is a tightly woven debut that travels easily between epistles, point of view shifts, and art criticism.

The novel follows Penny, an archivist and art historian, who for twenty years has lived beside and overseen an art collection housed in the type of decaying English manor house you would expect in a novel by the Brontës. Penny and her partner, Aidan, inheritor of the mansion, have largely lived at a pastoral remove from the havoc that floods, extreme drought, and increased wealth gaps have wreaked on English cities, now segregated into quadrants for the wealthy and for the dispossessed. Still, they feel the impact. The manor house, in need of unaffordable repairs, will be demolished, and Penny and Aidan are preparing to build and move into a mobile home next to what will soon become the house’s rubble.

As we read Penny’s diary entries, we learn that Julian, Aidan’s brother, plans to visit the manor house where he and Aidan grew up one last time before it is destroyed. A clear object of fixation as the months pass and his visit date approaches, Penny is plagued by nightmares about flesh-eating termites. Distracted and sleep-deprived, her days become foggy. “Time has been slipping through me,” she writes, “like water through a sieve. Entire decades seem to be swallowed up by an afternoon, a year fitting neatly into a single hour. I float in a haze, one minute standing before my work and the next walking down the streets with Julian.” Daily, she is pulled back into memories of time she spent with Julian twenty years before. “I feel as if I am standing inside a tank,” she writes, “and the memories are gradually rising higher and higher until one day, they will tip over the edge and I will drown.” True to the traditions of Gothic fiction, the past haunts the present, but Penny is unable to express what she longs to say. Though memories of Julian threaten to topple her, she can’t articulate the trouble with him until close to the end of the novel. Instead, she turns outward to find the words, interjecting short pieces of art criticism that ventriloquize her troubles.

The essays, which I take to be written by Penny, quickly reveal a pattern. Studying statues and paintings such as Giambologna’s The Rape of the Sabine Women (1583), Cellini’s Perseus With the Head of Medusa (1545–1554), and Ruben’s The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus (ca. 1618), she notes that the women are portrayed as “throbbing with erotic potential” though each work depicts a woman subjected to violence. In the hands of male artists, these female figures from Greek and Roman myths with “perfectly sculpted breasts” are shown taking pleasure in their own abduction, rape, and murder. By the time Penny confirms that Julian raped her twenty years ago, we understand that what presses upon her is both the memory of the assault and the weight of thousands of years of history that give scaffolding to a culture that still casts women as sexual commodities.

The novel builds up to the revelation of the sexual assault, but it’s the aftermath that Lai is most concerned with. Before the assault, Penny was professionally and personally close to Julian. Twenty years prior, she was a young art historian on fellowship at the manor house, studying J.M.W. Turner paintings that Julian himself purchased for the collection. She worked regularly with him, aimed to please him in the way one aims to please a boss, and felt attracted to him because of their shared love of Turner. Remembering what attracted her, she writes of warm evenings they spent on the manor house’s veranda, reading together and discussing art. “In those conversations” Penny reflects, “I saw a curiosity and thirst for knowledge that I recognized in myself at a time when I had assumed the accumulation of facts and ideas to be the key to the world’s mysteries.” She felt affinity for Julian and a burgeoning sense of trust.

When Julian assaults her, he effectively tears a rift between Penny and everything she cares about. She can’t return to the manor house; her own patron has displaced her from home and career. She wanders the streets of London for days, checking into a hotel so that she can wash her bloodied face and then sneaking unnoticed through the backdoor of her childhood home so that she can sleep. She rides trains all day and night, avoiding parts of London she visited with Julian. Even the Turner paintings she loves are now clouded by their association with him. In the days immediately following the assault, she wonders “if [she] would ever be able to read a book the same way, to look at a painting and know that it is beautiful, without thinking of what happened, what had been lost.”

Interspersed throughout Penny’s diary entries and essays are chapters of conventional narrative that grant us access to Julian’s point of view. A portrait of a man twenty years after he commits violent sexual assault, there’s potential in these sections for Lai to complicate our picture of Julian. I wondered, while reading, if Lai would ask us to witness his growth or to extend him sympathy or understanding. But Julian doesn’t evolve. A man who grimaces at the sight of the poor, a man who wonders why he should grieve his own mother, a man who sends women a list of their flaws after breaking up with them, a man who is certain the world exists for his pleasure, Julain remains irredeemable to the end. It’s never clear whether he is incapable of caring for others or simply unwilling, but it doesn’t matter: His impact on Penny is the same.

Echoes of W. G. Sebald’s ruins are everywhere in this novel, and in one chapter, we even see Penny loan out a copy of Austerlitz. But where the memories that weigh on Sebald’s protagonists walk them toward self-destruction, madness, and oblivion, Penny finds a way to reconstitute her life. We see her evolution framed most clearly through her art criticism. Early in the novel, the essays critique male gaze and violence in classical and modern art. Toward the end, the essays shift to contemporary female artists. In an essay considering Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Rape Scene) (1973), Penny offers a quote from the artist, who once said that “My art . . . comes out of rage and displacement . . . I think all art comes out of sublimated rage.” Later, writing about the memories and traumas embedded in Louise Bourgeois’s works, Penny writes that “Memories contain the seed of art.” Penny is an archivist, not an artist in the traditional sense, but still she finds an outlet for her own sublimated rage in her archival work, her criticism, and her diaries. As her criticism shifts from the victimization of women to female agency, we see Penny, too, shaping her narrative and regaining her sense of self. After the assault, she is eventually able to return to the things she once loved and fill her life with friendship, purpose, and a sense of home. As much as Landscapes is about destruction and decay, it is equally about picking up the ruins and rebuilding.

Agency is so often a core concern in climate change fiction, but the question is rarely What can we do to stop the crisis? That question, which pretends climate change is a singular problem rather than a constellation of crises, is perhaps too big to answer in a novel. In line with recent ecologically focused novels like Johanna Stoberock’s Pigs, Jenny Offill’s Weather, and Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint’s The End of Peril, the End of Enmity, the End of Strife, a Haven, Lai instead asks, What can we do to stop the crisis from robbing us of humanity? She offers us Penny—a character who finds a way to be despite trauma and a broken world.

Though Lai’s epistles tend to slip into extended explication and sometimes lack narrative momentum, Landscapes’s gradual, careful layering ultimately rewards. A formal nod to early novels like Samuel Richardson’s Pamela and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Lai uses the epistolary form—not exactly popular in fiction today—to show us that the past can be reconfigured to suit the future. Although it is in many ways a catalogue of struggle, Penny’s post-apocalyptic diary does offer hope. It tells us that, after the worst of things, storytelling exists, art still carries meaning, and life is possible.

Christina Wood is a fiction writer with short stories appearing in The Paris Review, Granta, McSweeney’s, Virginia Quarterly Review, and other journals. She is a PhD candidate in English and Creative Writing at the University of Georgia, where she teaches creative writing and composition classes.

This post may contain affiliate links.