[Visual Editions; 2014]

[Visual Editions; 2014]

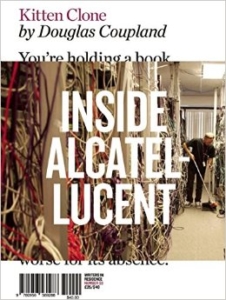

Half-way through Douglas Coupland’s new book, Kitten Clone, the engineer Joshua Agogbua raises the question of the day: “What are we learning about ourselves from all this technology that we didn’t know before we had it?” It’s a simple but profound query and Coupland attempts to engage it by profiling the global telecommunications company Alcatel-Lucent. As part of the Writers in Residence series, a project created by Alain de Botton after his stint in London’s Heathrow airport, Coupland, along with Magnum photographer Olivia Arthur, were given access to Alcatel-Lucent on three continents.

An obscure but logical choice given Coupland’s interest in technology, the book is an interesting if somewhat unsatisfying profile of this largely unknown company that’s responsible for building and maintaining much of the internet’s physical infrastructure; Coupland finds it’s another multinational trying to make a buck whose employees for the most part are uninterested in discussing the social and philosophical consequences of their technological endeavors.

Coupland, though, is more than willing to muse, in content but more importantly in style. By eschewing a standard business profile, the book acts as a site of conflict and translation between a waning medium — print — and an ascending one — the internet. Only now, with the foil of the personal screen, can we see how the book made our existence and how the internet, in turn, is doing the same. Coupland writes:

The now fading notion that our lives should be stories is a psychological inevitability imbued in readers by the logic of the book and fiction as a medium: focus; sequencing; emotional through-lines; morals; structure; climax; denouement. One can look back on the print era and witness true poignancy: readers the world over were determined to see their lives as stories, when, in fact, books are a specific invention that creates a specific mindset.

Marshall McLuhan looms here like dark matter though he is invoked by name only twice in the book. It’s a fitting pairing: for the critic McLuhan, all media manipulate our senses and thus our being, while Coupland has always sought to get down the texture of our accelerated digital existence — from Generation X to the “tech” novels of Microserfs and JPod to his short biography of McLuhan.

Lest we forget, McLuhan writes, the book performed its own radical revolution. In The Gutenberg Galaxy McLuhan traces the printing press’s transformation of an oral society into a visual one. Typography homogenized time and space through the fixing of letters on paper; rather than the simultaneity of experience that existed in multiple voices, the book created linear narrative. From here followed, he argues, individualism, commodification, and nationalism. Even what we call “close reading” is in fact a degradation of our once fine ear for language that developed in an oral culture.

As the web returns some orality to our society, our life as a narrative is breaking down. Time speeds up and fractures and loses its through line. But we have to look at the organizing source, says Coupland:

If you have a culture whose brains are “planned” by digital culture and internet browsing, you’ll have a citizenry who want their lives to be simultaneous, fluid, ready to jump from link to link — a society that assumes that knowledge is there for the asking when you need it.

While this shift is radical in many ways, the internet actually continues many trends that books began. McLuhan argues that in an illiterate society, where memory was robust because that was the only way to fix it, the book offered an on demand receptacle of knowledge. Print also gave individual voices a huge amplification system to address the world and eternized experience for the first time. The internet has intensified all these trends. I believe, by seeing their lineage in the book, it complicates the Manichean debate between print vs. web. Much of the alarm and vociferous discourse is warranted and needed to expose these effects, but as McLuhan and Coupland both state, neither is good or bad but simply is — this claim rings intellectually true while covering both critics’ staunch emotional inclination towards bibliophilia.

By importing the some of the tone, rhythm and texture of the internet into the book form, Kitten Clone counterpoints each medium’s effects so that we may know them in their detuned state. For it is still a book, bound and structured into Past, Present, and Future chapters. We expect narrative from such a non-fiction package. But Coupland — both subtly and explicitly — grates against the focused propulsion of the print medium by designing the text so there is a “surfy” feel. Here he imports the frustrations and joys of the net: “I wanted to mirror the way we look for information on the internet: its random links, its chance encounters, and its happy coincidences.” Coupland flits from one location to the next, one interviewee to the next, sharing mostly surface words, but relentlessly hurtling forward, chasing the promise of the horizon. His similes and metaphors often run on until you forget the geography of where you are, lulled into a surfing fugue of indeterminacy. Finally a declarative statement resituates the reader on the narrative line, conscious again and able to proceed.

Anyone who has opened up a computer and knows not how these sleek machines run can recognize the boredom of discussing these guts. Coupland does and the writer renders Coupland-the-reporter’s life more interesting. When the writer bores of the reporter’s subjection to tech and corp speak he daydreams the story forward. At one point he errs with some engineers and inquires about quantum computing, the answer sprawling down the page, flooding the margin till the ever-shrinking type disappears at the edge. Elsewhere, the CEO drones about business strategy and Coupland has Alphonse Garreau, an invented character, interrupt, which gives him the license to imagine a more compelling interview along philosophical lines.

Appearing first in the 19th century as a worker at the locomotive company that evolves into Alcatel-Lucent, Garreau features regularly throughout, often as an overly determined device. But there is logic to this cuteness: it’s revisionist history of the fabulist variety. Garreau finds a kitten in 1871 and wants to share the image of it with the world. As he reappears, the kitten obsession evolves with each new technology, culminating in a future where found kitten DNA is cloned. Coupland here invents the cause of the eventual effect, he imposes narrative on one that does not exist — we always talk about the ingrained narrative impulse of humans but we should instead discuss the narrative impulse of books. As McLuhan writes, “The notion of moving steadily along on single planes of narrative awareness is totally alien to the nature of language and consciousness. But it is highly consistent with the nature of the printed word.” One, in defense, might point to Paleolithic cave paintings that tell stories but they are not narratives in our sense; the images exist on the walls simultaneously, free of causal relationships. They reveal impressions of the world and a desire to eternize their experience but we do not recognize in it the same structure that rules our lives.

The British writer Ali Smith recently commented in The Guardian on fiction’s problem of rendering a world of simultaneity in a linear form, one page after another. “In a way that makes the novel a moral form,” she says. “You have to have sequence and consequence in the novel.” Of course, modernists and post-modernists challenged this stricture but despite these attacks on narrative the print medium still demands conformity of time and action — as do the au courant cable series that, as the claim goes, epitomize storytelling.

If our modern morality grew out of the cause and effect of narrative, then it’s easier to understand the challenge the internet poses to these ethics. A fluid medium seemingly devoid of consequence will of course assault our understanding of morality. How could it not? Think, what were the understood morals in an oral society before the printed Bible codified Christian cause and effect narratives? What will they be as we leave the causality of the book for the mess of the internet?

It’s the question: what do we know about ourselves that we didn’t know before? Coupland thinks we’re more curious and desire connection, we’re funnier and want to be heard. And anonymity is “the food of monsters.” Simplistic conclusions from a book that aspires to greater — again, the insight lies in style and not content. And yet we can see that many of these behaviors are the continuation of ones that evolved out of our relationship with books; technology accentuates and intensifies some while in other ways renders us completely new.

In this developing technological mediation of the world the centre unhinges — the understanding of our lives as a cohesive narrative — and gives way to something else. We don’t know what that will be. Another center, another transcendent mode to comprehend our lives? Or the opposite of center, the atomization of experience? As McLuhan writes of his study, “unconsciousness of the effect of any force is a disaster, especially a force that we have made ourselves.” Kitten Clone needles the reader into conscious confrontation with our technological behavior and asks us how will the internet make us be?

This post may contain affiliate links.