On a sunny day in early October, I strolled down Mother Theresa Boulevard, Prishtina’s main pedestrian artery. The boulevard was clamoring with its usual hubbub: men selling used books, popcorn, and chestnuts, and young people sitting in cafes lining the boulevard, leisurely sipping their third or fourth macchiato of the day. Eager as I was to enjoy my own lunchtime shot of caffeine, I almost failed to notice the red carpet, staffed by several bearded photographers, set up next to a still-partially-incomplete fountain and a pile of cement blocks.

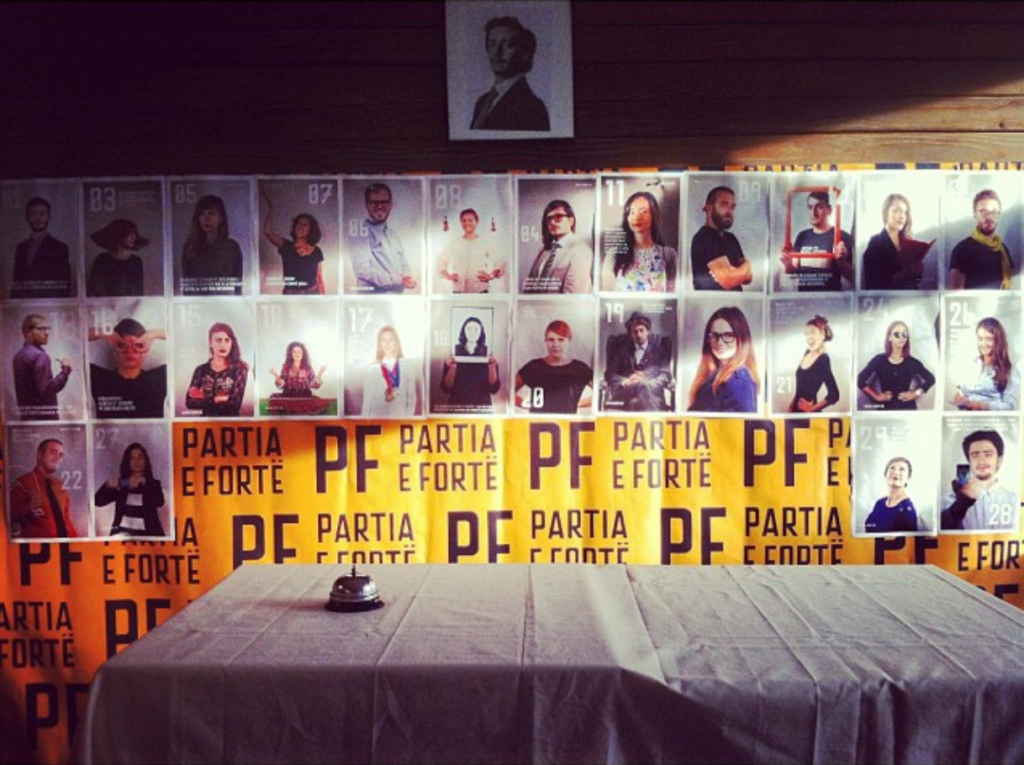

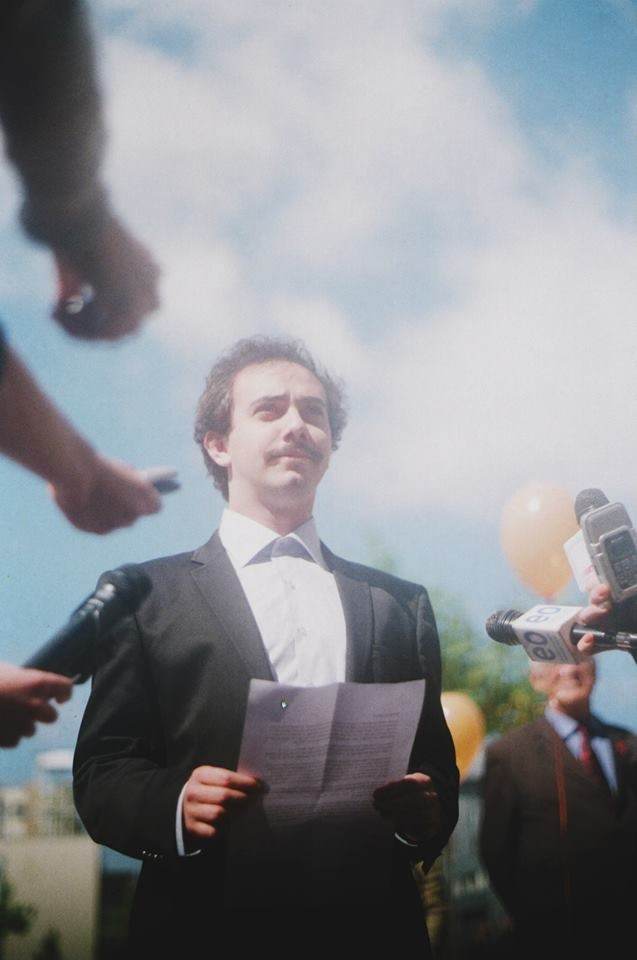

Visar Arifaj, Partia e Fortë’s “Legendary President” (Kryetar Lexhendar, in Albanian) was posing on the carpet, dressed for success in the party’s ‘uniform’ of a white button down shirt, cargo shorts, and a tie and surrounded by hordes of supporters and fellow party members. The occasion? A party press event inaugurating the boulevard’s completion. In truth, Partia e Fortë had absolutely nothing to do with the planning or funding of this project, but these sorts of promotional events — which involve taking sarcastic credit for something originally implemented by the Kosovar government — are the party’s trademark.

* * *

According to their Wikipedia page, Partia e Fortë or the “Strong Party” is Kosovo’s first satirical political party. I prefer to think of it, rather, as a political experiment gone terribly right. Arifaj and a group of his friends and colleagues conceived of the party over a year ago at Shallter, one of Prishtina’s most popular alternative late night bars. Partia e Fortë’s ideological basis is the sarcastic avowal that everything in Kosovo is perfect the way it is, and that preserving the status quo is the best option for Kosovo. For someone unfamiliar with the political state of affairs in Kosovo, this statement would likely be met with at least a raised eyebrow. For a resident of Kosovo, it verges on the absurd.

Partia e Fortë has existed in some iteration since 2012, with activities that were at first mostly restricted to Facebook and Twitter. When its official registration paperwork came through on June 20, 2013, just in time for the upcoming municipal elections in early October, the party’s popularity and visibility skyrocketed practically overnight. Consisting mainly of Arifaj’s friends and colleagues at the graphic design company that he co-founded, the party’s base includes web developers, designers, artists, bar owners, and a philosopher or two — all of whom are respected in Prishtina’s energetic alternative scene. Partia e Fortë’s use of puns and sarcasm to attack the current state of affairs is masterful. Its emblem, the Albanian flag’s double-headed eagle showing off its muscles, is brazen. 90% of Kosovars are ethnically Albanian, and the Albanian flag is displayed loudly and proudly throughout Kosovo. (Kosovo gained independence on February 17, 2008 after suffering for years under former Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic’s regime, which was characterized by extreme repression and the violent ethnic cleansing of Albanians.)

As with most compelling satire, Partia e Fortë does more than poke fun. The party has launched incisive commentary on the state of political affairs in Kosovo. Its actions, which on the surface might seem glib or insincere, resonate deeply with many disaffected Kosovars who have learned to shrug their shoulders in the face of elected officials’ rampant political corruption. The most powerful impact of the party, as party supporter Nita Deda said, lies in its ability to “reflect upon our country, not by fueling negativity or anger, but by making us laugh.”

Partia e Fortë gives a voice to these disenchanted Kosovars, who aren’t otherwise offered many outlets to vent their frustrations. In Arifaj’s words, the party effectively points out that “We, the people, seem to actually want to be lied to. And so we do a great job of keeping the worst in power through our own complacency — it’s a way of shifting responsibility away from ourselves. In this sense, we are all to blame for the state of affairs.” According to the party, this endemic complacency has created a situation where citizens prefer to only think actively about electoral politics every four years, and are comfortable letting others (qua elected officials) think about it for the rest of the time. Partia e Fortë has been instrumental in helping people realize the extent to which the system fails them on a daily basis.

The party’s role, explained one founding member, is to engage in “critical analysis of the existing state of the situation by rendering visible its limitations, inconsistencies and obscenities . . . instead of engaging in ‘futurist’ dreams and in acrobatic ‘creative’ exercises about the ‘ideal-future-to-come’ in the Republic of Kosovo.” The party’s purpose is thus to make visible the perversion of the political-ideological premises of Kosovo’s political status quo.

* * *

Partia e Fortë celebrated the official launch of Kosovo’s campaign season at midnight on October 2nd with a kick-off event (read: party) at Shallter. The bar was decked out for the evening in an excess of orange and black balloons. Trays loaded with Peja, the local brew, were distributed to fans “as a gift of The Party.” Amid catcalls and applause, Arifaj announced the launch of its official campaign event plan, cheekily titled “Lorem Ipsum.” He promised that the Party would “use the month to tell the people how important we are,” because “they need some empty promises so that they can continue to live their lives” — a self-referential quote referring back to its motto: “Ne Gjithmonë Premtojmë” or “We always promise.”

Partia e Fortë has made good on its promise of promises during the campaign. Its actions, most recently Arifaj’s night spent working as a bartender in Miqt, a popular local bar, stress that the purpose of most political campaigns in Kosovo is to make scores of promises to the masses — with the intention of ignoring them all after the elections. As such, the bartender stunt allowed Arifaj to “mingle with the masses so that he could understand their plight” so that the party could “then move forward with its real agenda after the elections and never do silly things like that again,” as he later stated in a televised interview.

Throughout October, political parties in Prishtina inundated their social media base with campaign messages. LED screens took the campaigns outside, blinking slogans furiously at people strolling down Mother Theresa Boulevard, the city’s iconic and lively main artery — each flash of the screen promising some iteration of “a better tomorrow for Prishtina.” Not to be outdone by these flashy displays, Partia e Fortë has also amped up its activities.

The party riffs almost too easily on the promises of other parties. Its strategy is to emphatically overidentify with the current state of political affairs as a means of pointing out the political system’s logical flaws while simultaneously creating room for any Kosovar citizen to participate in political discourse. “We don’t just critique the system,” said Arifaj, “we actually become it, and make it seem ridiculous from within.” The founding members of Partia e Fortë borrowed this political strategy directly from Žižek’s concept of overidentification, which he defines as “taking the system more seriously than it takes itself seriously.” This strategy is, for Žižek, the only means of creating real subversive potential. The Žižekian form of overidentification finds the logical paradoxes within the system, rather than imposing an external logic or ethic upon it to reveal its flaws.

Arifaj and his cohorts have drawn on and exaggerated elements of both the extreme nationalism of Vetëvendosje! (Kosovo’s nationalist ‘self-determination’ party), and the obsessive fixation with EU integration that’s become the cornerstone of other leading parties in Kosovo (notably PDK and LDK).

Through its satire, Partia e Fortë suggests that the ideological tendencies underwriting all of Kosovo’s prominent political parties and trying to hegemonize the social-political milieu need only slight exaggeration to appear ridiculous and nonsensical. This incisive systemic critique is why Partia e Fortë, in spite of its sarcasm, should be taken seriously — “not because its irony is fun, but because it expresses truths about the system that the dominant political parties — self-proclaimed as ‘serious’ — prefer to hide.” The role of the Party is to make the more serious “masks” of these other Parties fall away.

Playing off of Vetëvendosje!’s central lobby for the national reunification of Kosovo with Albania, Partia e Fortë proposed the reunification of Fushë Kosovë (a particularly grim industrial suburb) with Prishtina. The press release announcing this proposed ‘national unification with Fushë Kosovë’ perfectly mirrored Vetëvendosje!’s language, claiming that “many families are subjected to the unjust decision of previous regimes which divided Prishtina and Fushë Kosovë as different municipalities, and now feel the pain of this internal division.” As a party “dedicated to improving the lives of Prishtina’s citizens,” Partia e Fortë thus holds “that every family has the right and should live united and happily.” This joke plays directly into Vetëvendosje!’s cornerstone belief that all territory made up predominantly of ethnic Albanians (including Kosovo) should be joined back together with Albania (the “Motherland”) in order to recreate the landmass that was once referred to as “Greater” or “Ethnic” Albania.

Most of Partia e Fortë’s actions remain dedicated to the ruthless mockery of the Municipality of Prishtina along with PDK and LDK — the two leading political parties in Kosovo. The critique implicit in Partia e Fortë’s activities is that both these parties and the municipality focus more on kowtowing to the demands of the United States and the European Union than they do on working in the interest of their citizens. Large-scale and flashy events put on by the government (“Hey, Kosovo is European too!”) are the norm, laughable in light of the country’s infrastructural shortcomings. Consider, for instance, the Municipality of Prishtina’s recent unveiling of a fountain dominating one end of Mother Theresa Boulevard. The many-headed fountain is left on 24/7, spouting jets of water illuminated by garish multi-colored lights that fade in and out with each pump. Impressive (albeit tacky) as this might appear, Prishtina is wracked with frequent water shortages. The fountain is thus widely considered as a foolish waste of resources — both natural and monetary.[1]

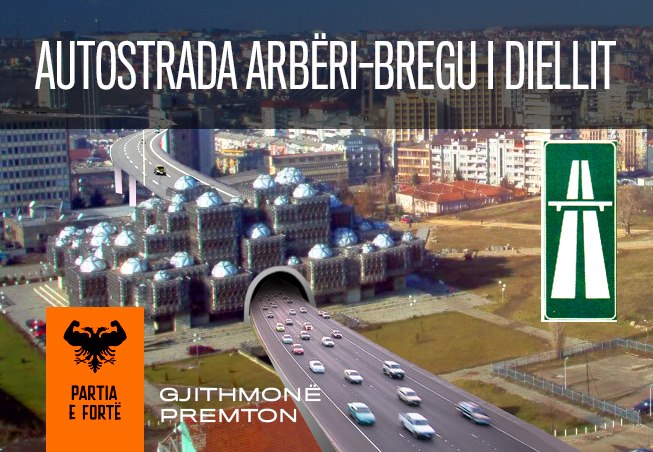

The brilliance of Partia e Fortë’s campaign activities lies in its uncomfortable near-approximation of the current government’s approach. The party’s unveiling of a ski resort plan in one of Prishtina’s neighborhoods is another particularly salient example. Aside from the obvious fact that the city of Prishtina has neither the climate nor the infrastructure to support a large-scale resort, the proposed plan would also permanently shut down the main road leading eastwards out of Prishtina to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia. The party cited the need to reconfirm their “pro-Western orientation and aspirations for EU and NATO integration” as the impetus behind this roadblock.

The notion of blocking the road to the East in order to appear pro-West is absurd, but is nonetheless an almost realistic simulation of the government’s obsession with reimagining Prishtina as a tourist destination as part of its lobby for EU and NATO integration.

In another press event, Partia e Fortë unveiled a construction plan for the “Transparent Residence” — a structure that bears striking resemblance to The White House — to comfortably house the “Legendary President.” The detailed proposal includes that the funding should come from the Prishtina Municipality, a “gift” from the people of Prishtina to their beloved leader. The party’s press release from the event (issued from the Office of Media and Propaganda) explained that the architectural similarities of the new project with the White House exemplify the old friendship between two peoples, and the name of the building is a nod to the practice of transparency “taught so diligently and persistently by our American friends, to which Kosovo and its electorate should always be grateful.”

This pitch-perfect sarcasm (particularly given that the event coincided with the second week of the United States’ government shutdown) plays off of the obsession that the leading political parties have with maintaining ties with the United States, and also addresses the commonly held opinion that American money in Kosovo is not exactly squeaky clean. The sarcasm is topped only by the party’s play on the notion of ‘transparency’ which is not financial, in this situation, but physical: “Since transparency is an important quality of the President and the Party, it is ensured through the installment of spectator seating within the house, which provides all the citizens without distinction access to recreational routines of the President.”

People do occasionally miss the point of Partia e Fortë’s deadpan sarcasm. When the party was first formed, Arifaj and other founding members of the party published an advertisement in a local online newspaper in order to gauge the public’s reaction. They designed a campaign poster proposing a highway that would run directly through the National Library — one of Kosovo’s most iconic buildings — in a thoroughly absurdist bid to connect two of Prishtina’s neighborhoods. Most caught on to the fact that this was commentary on “the Nation’s Highway,” a project begun in 2007 to connect Albania and Kosovo that so far has cost the two countries’ governments and various foreign contractors over 1 billion euro, and has generally been fraught with scandal. Partia e Fortë’s stunt nonetheless went over some of newspaper’s readers’ heads — the comments section was full of furious exclamations such as, “Look what they want to do to Prishtina — just think of the noise!”

In spite of these occasional difficulties in communication, Partia e Fortë’s base has broadened massively over the past month. According to Arifaj, this is undeniable proof that “something is working.” The party’s increasingly widespread popularity is evident in the sheer numbers of people who show up to its events, or who make daily stops at Miqt — a bar that serves as the party’s official headquarters — to catch up on its progress.

Partia e Fortë’s political stylings, unsurprisingly, appeal predominantly to the youngest generation of Kosovar voters. Arifaj and his cohort rely on Facebook statistics to understand the demographics of their constituency. They describe most potential voters — especially those outside of the party’s very Prishtina-centric inner circle — as those who “weren’t giving a fuck until now . . . people who were never before inclined to be politically active . . . young people who never felt forced to pick a political side.” These voters may be drawn in by the party’s provocative and comedic activities, but Arifaj suspects that there’s more to it than that.

While Partia e Fortë’s actions are humorous and sarcastic in character, its commentary on the political status quo makes the lasting impression. The significance of this commentary lies in the fact that it does not function only as a critique but has actually worked to narrow the gap in Kosovo politics between the citizen and the politician. The reason for this is multifactorial: firstly, the party allows any citizen of Kosovo to become a Vice President by simply filling out a form, suggesting that all citizens are on a level political playing field; secondly, it has opened up the possibility for any Kosovar to actively engage in the political sphere by providing an accessible channel through which the average citizen can voice their discontent; and thirdly the party has proved nimble in its ability to respond to these voices, and to loudly broadcast these discontents to the wider public. It’s this broadening of the political playing field that makes Partia e Fortë more than just a well-developed satire and a ruthless mockery of Kosovo politics, and allows it to function as an actual party with a very real base.

It is, perhaps, in part Kosovo’s size that allows this political experiment to work. In a country the size of the United States, as Arifaj pointed out with a bit of a smirk, citizens are often forced to choose from between a bad and a worse option. In Kosovo, with a population of almost 2 million — roughly that of West Virginia — there’s at least some room to play around with the existing political structure. This flexibility also owes to the relative newness of Kosovo’s democracy, and to the fact that the political system is not yet as solidified as it is in the United States. Kosovo’s political future thus is not marked by the same sense of inevitability.

* * *

Partia e Fortë has its fair share of critics, who fall mainly into one of two categories. Firstly there is the conservative and nationalist position. This position maintains that the country’s very dark period of poverty, unemployment, and political instability is far too serious for such a (self-)ridiculing enterprise, which works only to undermine the real political struggle on the ground. Kosovo, for starters, is the second poorest country in Europe based on GDP per capita, and the unemployment rate in Kosovo is over to 40% — closer to 55% for youth aged15-24.) The other critique is quasi-leftist, and argues that Partia e Fortë is nothing but the postmodern performance of some middle-class millennials who, drunk off some stereotypically hipster nihilism, have responded to the status quo with a reactionary but ultimately meaningless stunt.

As I see it, what both of these critiques miss is that Partia e Fortë’s popularity, and the impact that it’s already had in Kosovo, have solidified its role as a real and much-needed political party. At this point in time, the antagonism in Kosovo’s political scene is no longer between Vetëvendosje! and the leading political parties, but between those two and Partia e Fortë. The party, with its waves of incisive commentary, hilarious actions, and the unprecedented (and unforeseen) impact it’s had on the political scene, has altered the ideological climate that gave rise to the other two.[2] In other words, it is likely that the sentiments that Partia e Fortë espouses preceded its founding, but the party gave them a body and a voice, and in actualizing them created a very real and perceptible threat to the ruling parties.

What may perhaps have started as an ambitious joke now has completely serious implications, and at this point, numbers, polling, and the results of the election on November 3rd are almost beside the point.[3] That said, it still bears mentioning that as of October 21, Arifaj was listed as the fifth most popular politician in the Municipality of Prishtina out of nine.

Partia e Fortë has brought to life a form of activism that was at best dormant, and at worst absent in today’s Kosovo. Ultimately, there’s something particularly incredible about seeing a political scene shaken to its core by something so contemporary and unique in a brief four-month period. It’s no exaggeration to say that the party has made waves in Kosovo’s political scene, throughout the Balkans and beyond.

Photos © Jetmir Idrizi and Brilant Pireva

You can find more on Partia e Fortë here and here.

[1] One of Prishtina’s most well-regarded performance art group, HAVEIT, dedicated an entire performance to this critique of the fountain. Most of the follow-up press is in Albanian, but this article is well worth a read.

[2] Consider Jacques Lacan’s 1 + 1 = 3 equation. In Lacan’s terms, the official antagonism of the Two (1+1) is always-already supplemented by the invisible third. As such, the existing antagonism is never between the Two official forces, but between them and the invisible Third (a thing which exists only insofar as it declares its existence to the world). As applied to the Kosovar case, the antagonism in Kosovo’s political scene is not between Vetëvendosje! and the other ruling parties, but between them Two and the Third (Partia e Fortë’s) which, now that it actually exists, undermines the ideologies that gave rise to the Two.

[3] As one Party member put it, perhaps the only way to counter these overly-simplistic critiques is to consider the well-known joke from World War I. Towards the end of the war, the Germans wrote a telegram to the Austrians saying “here on our front, the situation is serious but not catastrophic,” to which the Austrians replied, “Well, on our front, the situation is catastrophic but not serious.”

This post may contain affiliate links.