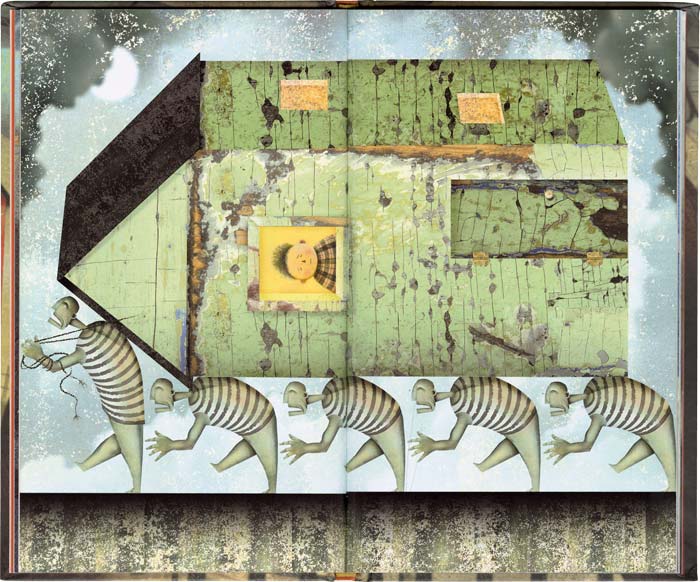

Illustration by Lane Smith from The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip

Illustration by Lane Smith from The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip

I was happily surprised and a little confused when I heard that George Saunders had written a children’s book. On the one hand it seemed fitting that a writer who deals in the fantastical and surreal would work in this genre. His prose is frank, without flourish, and often non-linear — good for communicating with and relating to kids. His writing is a reminder that such qualities should not be relegated to children’s fiction. Saunders’ normal subject matter, however, would not be considered “child friendly.” The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, like much of his other work, depicts disparate people responding to disaster. For Saunders, crisis is often a foregone conclusion, a reality of everyday life. Social mores and idealistic principles prove flimsy, as disaster and defeat become the glue that increasingly holds people together. Much of Saunders’ writing would be considered too dark for Children’s fiction, which if anything has a reputation for being too idealistic, too committed to acclimating children to those social norms that for Saunders are constantly crumbling beneath our feet. However, I have also been told that kids have the uncanny and frightening ability to observe things as they are, even though they are often assumed insufficiently jaded. This book as well is uncannily poignant in the sophistication of its message, despite the fanciful simplicity of its story.

The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip is a satire that parodies those grasping at notions of political responsibility in the context of neoliberal capitalism. Satire is an important and very intentional tool for Saunders. In a 2001 interview with The Missouri Review, Saunders explains that good satire combines a critical clarity — what he calls “clear sight” — with compassion and understanding. We laugh, perhaps uneasily, at Saunders’ dystopian worlds and his misguided characters, partly because we can recognize them for what they are. But for Saunders, this kind of clarity cannot come, or should not come, without some bit of mutual recognition and understanding. Satire is certainly critical, and we laugh at the expense of its object, but we also laugh because it contains elements of parody: it is a twisted imitation of what we identify in ourselves and elsewhere. These terms, of course, are slippery. Parody and satire are distinct, the former working through dissimulation and the latter working through simulation, yet it is hard to speak of one without the other, as they tend to overlap, albeit to varying degrees. The implication is that parody, no matter how biting, no matter how satirical, comes from a place of identification with its target. And when Saunders, in his interview with The Missouri Review, makes a clear distinction between political satire that “works on the assumption that they are assholes”, and his own writing, which works on the assumption that “they are us on a different day,” he is arguing that good satire requires parody. This first kind of humor, the kind often trotted out by Bill Mahr and occasionally Jon Stewart, appears smug and dismissive. It is perhaps uninteresting and ineffective because it does not attempt to understand what it critiques and because it takes its own critical voice too seriously.

While Saunders identifies the parodic quality of satire to be key to politically meaningful humor, French theorist Jean Baudillard, in his classic book Simulacra and Simulation, argued that parody is always at odds with political meaningfulness. According to Baudrillard, parody, by muddling the distinction between the object of satire and its author, “renders submission and transgression equivalent,” and “cancels the difference upon which the law is based.” Baudrillard is being a bit dramatic here, and yet there is certainly reason to distrust parody, considering that it is frequently invoked retroactively as a way to rebrand politically offensive and reactionary content as benign or transgressive simulations of that content. Still, for Saunders, it is parody that makes it possible to understand problems and then manage them accordingly. “If you see something plainly,” says Saunders in the same interview, “without any attachment to your own preconceptions of it and without any aversion to what you see, that’s compassion, because you’re minimizing the distinction between subject and object. Then whatever needs to be done, you can do it quickly and efficiently, to address whatever the suffering is in that situation.” This pragmatic view is admirably wary of smug political satire, the kind more narcissistic and more concerned with being on the right side than it is constructive. But the political problem raised by Baudillard is still relevant. If parody is valuable because it on some level accepts rather than wishing to dismiss or negate its targets, then doesn’t that parody risk becoming apologetic?

In Gappers of Frip, Saunders depicts, on a much smaller scale, an economic system prone to crisis. This crisis threatens and gives birth to a political community shaped by the agency of those who learn to effectively manage that crisis. The very small village of Frip consists of three families, living in shacks on the edge of a seaside cliff. They are goat farmers, who for all of their goat-farming years have dealt with the gappers: orange, baseball-sized critters who latch onto their goats and torment them with a “continual high pitched happy shriek of pleasure.” Every day, eight times a day, the children of Frip brush the gappers off their goats, put them into their “gapper sacks” and throw them back into the sea.

The main protagonist is a young girl named “Capable,” who lives alone with her father.

One day a particularly smart gapper (they aren’t very smart) calculates that Capable’s house is a few feet closer to the sea than the other two houses in the village. Capable wakes up to find that the gappers, instead of equally dividing themselves among the three goat farms, have converged solely on her goats. She turns to the other families for help, but to no avail. Ms. Romo, a loud opera singer with two dimwitted sons, and the Ronsens, a snooty couple with two snootier daughters, attribute their new-found freedom neither to the geography of Frip, nor to chance, but rather to a singular miracle, a sign that those who were spared must somehow deserve it.

This reasoning is a rehashing of the classic liberal principle of equal exchange, but one that confuses cause and effect. It’s not that a person gets what they deserve — a fact measured by the value added through work — but rather that a person’s value is measured by the fact of what they receive. It is a slippery notion of personal responsibility and one that parodies the incongruousness of Ayn Rand style individualism. “I believe we make our own luck in the world,” says Sid Ronsen, “I believe that, when my yard suddenly is free of gappers, why, that is because of something good I have done.” Here luck configures as something that can affirm a given picture of reality and individual agency, while at the same time disavowing the personal actions and material situation that preceded the gapper infestation.

Reality soon catches up with the Ronsens and the Romos while Capable, demonstrating her admirable capability, sells her family’s goats and tries to make a living catching fish. The Gappers move on to the Romo family, and Ms. Romo, unwilling to forfeit her new-found privilege, moves her house a few feet ahead of the Ronsens’. What ensues is a vicious cycle of competition as the Ronsens and the Romos fight for the gapperless yards they feel they deserve, parodying the cycle of fear and entitlement that motivates suburban flight. Instead of suburbia, however, the Romos and Ronsens end up pushing their houses into a swamp. Ultimately it is Capable who saves the day by convincing her neighbors to adapt, to work together in order to manage the gapper infestation instead of conceiving methods of avoidance or assuming they are immune. Capable invites her neighbors to learn how to fish, and together they work to produce the goods necessary for their survival.

Still the anxieties and material necessities that generate and are generated by this crisis are not done away with. Rather, they become a springboard for communal activity in the interest of each individual. This is a book about managing crisis, and accepting the impulses of fear and greed often associated with capitalism, instead of trying to negate them. It is a fable seemingly in the spirit of the liberal welfare state. It recognizes society’s tendency towards dystopia, and understanding the inevitability of crisis, personal interest, and fear, attempts to integrate such realities into a pragmatic and imperfect social project. But in a world where the most we can hope for is not perfection but improvement, and in a world where our picture of reality is always on the verge of collapse, by what standards can we act in the face of crisis? What will happen if the gappers develop a taste for fish?

My best guess would be to return to Saunders’ understanding of satire, of critical perspective tempered by compassion. Capable, refusing the opportunity for poetic justice, does not turn her back on those who abandoned her, and instead acts out of compassion. She does this, for better or worse, because she, like the reader, can find humor in and identify with the experience of being misguided by situations she does not understand. This also leaves the reader with the impression that people’s attitudes are often shaped by forces that cannot be fully coopted. In this context, dismissing the delusions associated with neoliberalism misguidedly presumes immunity to being delusional. Among the more preachy of political satirists (Jon Stewart, Lewis Black, Bill Mahr etc…), this presumption is particularly glaring, and it begs the question of whether it wouldn’t be more constructive to appreciate the delusional for who they are: humorous and disconcerting parodies of ourselves, or even simply “us on a different day.”

That being said, this conception of parody disregards systemic realities that cause people to act self-destructively, or think misguidedly. Saunders identifies crisis as the inevitable and motivating force behind politics, and delusion as its mode. Those who continue to believe that there are greater locatable and cooptable structural dynamics behind those crises may find The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip insightful, but lacking. Regardless, this is a book that most kids, let alone most senators and congressmen, would benefit from reading.

This post may contain affiliate links.