[University of Nebraska Press; 2013]

[University of Nebraska Press; 2013]

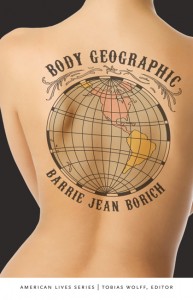

Barrie Jean Borich writes, “Maps are made of more than facts, are histories of what we believed, loved, feared, as well as who we are.” A number of books in recent years explore this imaginative terrain of maps. Peter Turchi’s Maps of the Imagination examines the map as a metaphor for story and likens the work of a writer to that of a cartographer. Rebecca Solnit’s Infinite City is an atlas of the San Francisco Bay Area, from the locations of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo to the lost industrial city and the sites of modern conservative power. In Atlas of Remote Islands, Judith Schalansky chronicles the lore of fifty distant islands, none of which she has actually visited. As in these books, in Body Geographic, Borich engages in the practice of literary mapmaking. She uses the map as a construct to examine her family history and her own life, and in doing so, creates an atlas of the dislocations and longings that drive American migration.

The Midwest is Borich’s landscape. She has the skylines of Chicago, where she was born, and Minneapolis, where she now lives, tattooed on her lower back. Even though it is not the most intimate part of her body, the pain is excruciating when the artist inks her skin. The Amtrak she rides between the two cities is called the Empire Builder for a Saint Paul railroad magnate; the line, which extends to the Puget Sound, was a part of the frenzy of the western expansion. The tallgrass Midwestern prairies were a void to dominate between the power centers of the East and the mineral wealth of the West. She grew up in the steel mill suburbs of Chicago’s South Side, where her great-grandparents arrived from Croatia; they had landed on Ellis Island just before America imposed strict quotas on newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe. The South Side is now a landscape of ruin: only shells of former factories remain.

In these essays, or maps as she calls them, Borich explores the way geography can serve as the solution to life’s problems. A geographical solution, she writes, “is when we move to a new place in order to make ourselves over, and thus avoid confronting the reasons we needed an overhaul in the first place.” Borich traces this longing for self-creation. Her immigrant great-grandfather remained dissatisfied in the South Side, left his wife and children, and continued moving west. He died in the coal mining town of Butte, Montana, of black lung. Her grandmother, as she slides into dementia, recounts her trip to Hong Kong, where she believes she crossed into Communist China and ordered a tea set to be delivered to Chicago. Her brother’s military job takes him to a different city every two or three years; in San Pedro, just south of Los Angeles, he strikes up acquaintances with the old Croatian fishermen who grew up in their family village. Her mother sees the coffee percolator as a symbol of her escape from the projects, while her father introduces her to jazz, his refuge.

Borich extends the map to explore her own corporeal longings as well. “The body is a stacked atlas of memory,” she writes. Like cities, the body is physical. They both have shadows that lurk beneath the surface, spaces for which our maps are often unreliable. Borich’s geographical solution is Minneapolis, the western half of a double city bisected by the Mississippi. In her twenties, she struggles with alcohol and longs to be awake in the world. She follows a boyfriend to Minneapolis, even though she is ambivalent about the relationship and beginning to explore her attraction to women, as she wants to break away from the terrain that led her to drink. In Minneapolis, she works as a waitron and steals drinks before she leaves work every night. She wanders in the dim streets, impetuous to the risks of being out alone in the hours before dawn, looking for the city of her dreams. It was not so much the city but a new lover who motivates her to sober up: Linnea, now her lesbian husband, fulfills her longings.

In Body Geographic, Borich reminds me of the surveyors who mapped the West. They got lost in blizzards and arrested for trespassing into Mexico, but they came back to tell the tales. Through their mistakes, we understood the terrain better. These men of empire believed they ventured into an uninhabited continent; Borich on the other hand knows that her landscapes are woven with memories and histories. The terra incognita she seeks to map is instead the caprices of the heart, a space that is ultimately impossible to chart accurately. But her maps show us how our desires are rooted in and our psyches shaped by the places we inhabit.

This post may contain affiliate links.