In Mexico City, my family hires a guide and boat to see the floating gardens of Xochimilco. Big, weepy trees line the muddy canals, roots adrift on the water. Canoes tethered to hand-hewn docks clank about: neighborhood parking spots. People live here, and so do axolotls. I ask our guide if he knows where to find them here, in their only native habitat. He frowns, gazing into the dark water. “Supposed to be down there,” he says, but prospects seem grim. He secures the boat in front of a large tent with a sign: Reserva ecológica. A woman in a purple tank-top pokes out and lifts a flap as we amble ashore. Inside is a sad, sparse zoo of local reptiles and amphibians, curled up and stiff in tiny glass tanks. The woman tours us around, tapping at the snakes, scooping up a tortoise for us to pet or poke. In every one of my father’s photos, I look horrified.

In Mexico City, my family hires a guide and boat to see the floating gardens of Xochimilco. Big, weepy trees line the muddy canals, roots adrift on the water. Canoes tethered to hand-hewn docks clank about: neighborhood parking spots. People live here, and so do axolotls. I ask our guide if he knows where to find them here, in their only native habitat. He frowns, gazing into the dark water. “Supposed to be down there,” he says, but prospects seem grim. He secures the boat in front of a large tent with a sign: Reserva ecológica. A woman in a purple tank-top pokes out and lifts a flap as we amble ashore. Inside is a sad, sparse zoo of local reptiles and amphibians, curled up and stiff in tiny glass tanks. The woman tours us around, tapping at the snakes, scooping up a tortoise for us to pet or poke. In every one of my father’s photos, I look horrified.

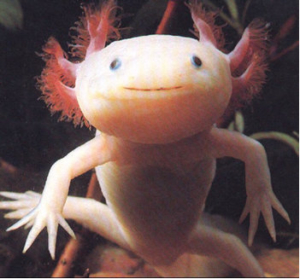

In “Axolotl,” by Julio Cortázar, the narrator is obsessed by the species of salamander with the sea-monkey face and humanoid hands — so obsessed that he turns into one. Axolotls are real animals, with unusual qualities beyond their appearance: they can regenerate limbs and organs and are neotenic, which means they reach sexual maturity without metamorphosing from their larval phase.

“It was their quietness that made me lean toward them fascinated the first time I saw the axolotls,” says the story’s narrator. “Obscurely I seemed to understand their secret will, to abolish space and time with an indifferent immobility.” This “secret will” is what Cortázar understands, and performs, in the space of the story. The narrator reveals his transformation in the first paragraph: a perspective Cortázar effortlessly balances with the story’s unfolding. Like much of Cortázar’s work, “Axolotl” hangs in the fault line between reality and the fantastic, past and present. You could also say it’s not unlike the animal itself, which lives a life of suspended development.

The keeper leads us to a corner of grimy aquariums. There is my axolotl, drifting along the bottom of a tank. It is as Cortázar describes: rose-colored, translucent, like a glass figurine. A weird, haunting beauty. I crouch in front of the glass. Its little red eyes stare back. “Their blind gaze, the diminutive gold disc without expression and nonetheless terribly shining, went through me like a message: ‘Save us, save us.'”

“Now she’s happy,” says the keeper. Is that how I look? She asks if I want to hold it, but I’m nervous I’ll rub off its special mucous that repels predators. “No predators here,” she says, scooping up the writhing creature. It clings to her with tiny, finger-like digits. God help me, I can’t resist the compulsion. She places the axolotl in my hands. It feels like cold fear. Be free, I want to say, like in the story. But in the real world, in a hot tent over a murky tank, it’s just sad. The axolotl slips out of my grasp and into the water.

Before Cortés arrived, Aztec farmers built a network of islands on Lake Texcoco, south of their city. They plotted the islands with beans and chile, and kept them lush with muck and water from the adjacent canals. Conquistadors noted that the Aztec capital – with these verdant gardens rolling into the royal city of pyramids and palaces – was more breathtaking than any in Europe. Then they leveled most of the pyramids and filled in most of the canals.

Today Xochimilco is overrun with non-native fish, its land overgrazed by cattle. Mexico City has never stopped growing, so pollution chokes the canals. It’s no surprise we couldn’t find axolotls in their native water; in 1998, Mexican biologists surveyed 6,000 axolotl per square kilometer. A decade later, there were 100. It’s not clear when the city will activate efforts to rehabilitate the region. Also not of help: handsy tourists like myself.

In the cab ride back, the sights of downtown Mexico City scroll past. Ruins of the Templo Mayor beetle at the feet of high-rise apartments. Guards change out before Maximilian’s palace, home of Mexico’s one-time Austrian emperor. At the end of the 19th century, Germany admired Porfirio Díaz’s tyrannical presidency so much that they sent over a set of hand-carved street organs. Buskers crank plinkety tunes from them today. Like Cortázar’s story, the city exists along a temporal fault line. Its histories uplift its present. But in Xochimilco, it seemed to me, the spot is too hot. In their own home, axolotls are slipping beneath a heavy modernity. “They were like witnesses of something, and at times like horrible judges… They were larvas, but larva means disguise and also phantom.” Soon, they may be but ghosts.

This post may contain affiliate links.