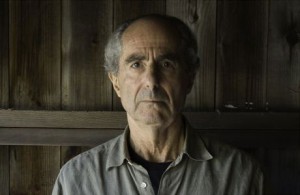

The recent announcement that my favorite writer, Philip Roth, has retired at the age of 79 has left me thinking about the great man’s legacy and the state of American literature. In a lot of ways, Roth is like Fidel Castro (who, if memory serves, steals the love interest of Roth’s fictional alter-ego Nathan Zuckerman in one of the many memorable and funny twists in that 9-book saga): even those that despise him have to respectfully cede to his achievement and longevity.

The recent announcement that my favorite writer, Philip Roth, has retired at the age of 79 has left me thinking about the great man’s legacy and the state of American literature. In a lot of ways, Roth is like Fidel Castro (who, if memory serves, steals the love interest of Roth’s fictional alter-ego Nathan Zuckerman in one of the many memorable and funny twists in that 9-book saga): even those that despise him have to respectfully cede to his achievement and longevity.

One of the factors that adds to Roth’s stature is that he seems to have outlived almost all of his major contemporaries. Taking a narrow view, Roth really is the last man standing of a specific demographic, those dubbed the “Great Male Narcissists” and/or “Phalocrats” by David Foster Wallace, who is himself very, very dead. The things is, Roth was always one step above the other writers of that class, especially the other Big Two he’s often lumped in with: Norman Mailer and John Updike. Roth’s work was more consistent than theirs, and when his fiction reached for larger themes he was less likely to embarrass himself. When those two passed in short order (along with George Plimpton) it really did seem like Roth was the only great writer of that generation left. Shortly before either of those three had bought it, their own senior class president, Saul Bellow, had expired. Shortly thereafter followed Kurt Vonnegut, J.D. Salinger and Gore Vidal. Roth was looking more and more like The Highlander of modern American Lit.

Of course, that is not the case. There are plenty of great writers from his generation still kicking: Toni Morrison, E.L. Doctorow, Cynthia Ozick, Ursula K. Leguin, William Gass. All alive and (presumably) well, though in their senescence. Then there are the other “Big 3,” at least as far as myself and Harold Bloom are concerned. These are the three living American writers who Bloom described as having “touched the sublime”: Cormac McCarthy, Don Delillo and Thomas Pynchon.

My personal veneration of these writers doesn’t come from reading Bloom, it just happens to match up with his own take. The standard argument against proclaiming them so, besides the obvious one of it being purely a matter of personal taste, is that they’re all old white guys. Which is true, they are. I’m not interested in arguing the merits of multicultural representation in my own personal taste; I just want to look at where we stand now that Roth has called it a day and the field of giants has narrowed by one. Enough has been written about all of these writers that going over their entire legacy would take more space than is appropriate here, so instead, I decided to look at where they stand since the turn of the millennium. One thing these writers all share is that they each published a major work near the end of the last century, specifically between 1997-1998, the period in which Roth released his most well-known novel, American Pastoral, the first of his decade defining American Trilogy, which summed up the defining madnesses this country underwent following the Second World War, right up until the clock struck midnight on the 20th Century.

Since then, all three of these novelists have published again, but it was during that moment when, taken as a group, they seemed to loom the largest. What’s the landscape look like now? Who’s looming shadows have declined, and who have grown bigger?

Thomas Pynchon:

Whereas Roth may come off as more extroverted at times than he actually is, Thomas Pynchon is our most shadowy literary figure, at least now that Salinger is sleeping with the banana fishes, which both adds and detracts from his stature. No one knows if he’ll put out a book in the next few years or never again. The time between the release of his books isn’t all that great these days, at least nothing compared to the 17 year gap between 1973’s Gravity’s Rainbow (a once in a generation masterpiece of the highest order) and 1980’s Vineland.

In ’97 he dropped his second magnum opus, Mason & Dixon, a gargantuan post-modern historical epic that he’d been working on since 1960. People didn’t know how to react to it at the time, but over the last sixteen years its reputation has grown very large indeed. It took ten years for him to release his next novel, Against The Day, which is so large it actually makes Gravity’s Rainbow and Mason & Dixon look like normal, readable books. His latest novel, Inherent Vice, came out a short 3 years later. Both were met with mixed reviews, but as with everything Pynchon does, who knows how they’ll be regarded down the line.

Far as his place in this pantheon goes, he’s Pynchon: you never know when he’ll drop something new on you. Paul Thomas Anderson has an adaptation of Inherent Vice in the works, so that will likely move the spotlight over to him when it’s released. Who knows, maybe it’ll even draw him out of seclusion. If that seems unlikely, consider the case of…

Cormac McCarthy:

Until 2007, McCarthy was almost as reclusive as Pynchon. Having finished his own epic Border Trilogy in 1998 with the disappointing Cities On The Plain, it was eight years until the release of No Country For Old Men. Up to that point, there were exactly two available interviews with the man. Everything changed one year later when he released The Road, his most widely read novel by far. Though the apocalyptic tale is crushingly bleak and brutal, it was a smash hit thanks to being awarded The Pulitzer Prize and, far more importantly, being chosen by Oprah for her book club. Speaking as someone who at that point was very familiar with McCarthy, it was bewildering seeing the confluence of his vision and the queen of all media’s media blitz. Even more bewildering was watching him appear on her show to give his first on camera interview. Though he seemed uncomfortable throughout, it marked a turn which brought him into the public spotlight.

One year later the Coen Bros made an brilliant, Oscar winning film out of No Country and suddenly McCarthy was everywhere. Adaptations of The Road and his play The Sunset Limited followed, and his masterwork, Blood Meridian, has become one of the hottest properties in Hollywood. There are now several interviews with the man, including one on NPR where he shoots the shit with Werner Herzog. He’s written a screenplay entitled The Counselor that is currently being shot by Ridley Scott and which will star Brad Pitt. Rumor has it that he also has a new novel in the works, which should be interesting not only because any book by him is an event, but because The Road truly does read like the culmination of the themes of all of his novels up to that point. More than any other artist, it will be fascinating to see where McCarthy goes next. It’s fascinating in the same way as it has been to watch the progression of…

Don Delillo:

Of all of the writers listed, Delillo is the one that I can least imagine retiring. Whereas Roth, Pynchon and McCarthy, to one extent or the other, mostly reflect on the past, Delillo has always been the most modern of writers. He is able to distill the anxieties of the the current landscape so perfectly that he’s people tend to look at him as a kind of Nostradamus figure. His meditations on terrorism and environmental disaster and pop culture ubiquity and the growing sentience of multi-national corporatism and the, uh, transient nature of the World Trade Center prior to even the first attacks on it, set the stage for their eventual realization in the real world. In 1997 the Towers were front and center on the cover of his magnum opus, the National Book Award winner Underworld. He’d never put out a novel of that scale before, and critics and fans were blown away by it. It managed to — like McCarthy’s The Road — sum up the major themes of his life’s work prior to it, the largest of which being the anxiety of life under The Bomb.

Since then, with the cold war seeming almost quaint when compared all of our various active wars, Delillo’s output has remained as current as ever, but the work itself had failed to connect in the same way as Underworld and the novels (White Noise and Libra) which came before it. The general consensus was that this latter part of his career saw him losing his relevance with mediocre novels, something to be expected of most writers. That consensus is currently undergoing a reevaluation at the moment, especially in regards to his 2001 novel Cosmopolis. Part so this reevaluation is due to David Cronenberg turning it into a film, but it mostly has to due with the novel’s themes of financial disaster and large spread anti-capitalist protest. It was published in 2001 and now, in the wake of the financial sector’s crash and the Occupy movement, the story not only takes on a new relevance, but, as The Los Angeles Review Of Books wrote Delillo has “once again taken on the mantle of artist-prophet.”

Totally non-provable, completely biased and probably wrong Conclusion:

Because Delillo looks not just at today’s world, but that of the future’s, and because my (imaginary) gambling-addicted drifter mother always taught me to bet on a sure thing, I think he is, in the wake of Roth’s exit, going to slowly start being recognized as The Great American Novelist of our time. McCarthy has seen the biggest boost in popularity and awareness, and young men especially continue to flock to his books the same way young men have always flocked to his own hero, Hemingway. But it will be Delillo that we look to for a diagnosis of what it is that is going to infect us, as Americans, next. If the antiquated notion of the novel as a social thermometer holds still holds any relevance, that, to me, will make Delillo the writer American’s turn to first, and then subsequently drop their pants and bend over for.

At least until Roth comes out of retirement, like we all know the old bastard will.

This post may contain affiliate links.