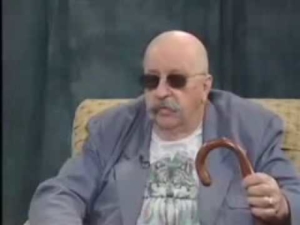

Gene Wolfe was born in 1931 in upstate New York and grew up in Houston, Texas reading pulp science fiction and fantasy. He attended Texas A&M University, dropped out, joined the Army and served in Korea. When he got back he returned to college, got married, and became an industrial engineer for Proctor & Gamble, where his most noted accomplishment was helping to create the machinery that manufactures Pringles.

He started writing short stories, sold a few, then in 1970 published a straight Science Fiction novel that he later decided wasn’t any good. Two years later he published The Fifth Head of Cerberus, a very good book that’s either a novel or a collection of three novellas, depending on who you ask. Each piece in the book can stand alone, but read together they enrich and complicate each other in remarkable ways. Fifth Head is set light years from earth and includes robots and shape-shifting aliens, but it also contains echoes of Proust, a series of unreliable narrators, and a deep enough treatment of contemporary post-colonial issues to satisfy Edward Said.

Having admirably flexed his literary chops while wading in the tributary waters of genre, Wolfe then stepped into the mainstream for his 1975 novel Peace. On the surface it’s a realistic portrait of an old man, Alden Dennis Weer, who sifts haphazardly through memories of life in a small Midwestern town. The storytelling of this kindly figure is a mite confusing, as he tends to move on to the next anecdote before he’s finished with the first, but it’s still easy to enjoy the novel as a wholesome slice of American pie. Except that there’s a lingering aftertaste to every bite. Why are Weer’s successes so closely associated with the failures of others? Why do so many of his anecdotes take a turn into carnivalesque weirdness? Even a casual reader begins to realize there’s a darkness in Weer’s heart, and a truly attentive one will see that the stakes of the novel are far higher than they appear. “Life and death” doesn’t begin to cover it.

Peace, a subtle, inverted version of Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus reset in Winesburg, Ohio, was appreciated by the cognoscenti, but the wider public didn’t embrace it. Wolfe gave up his bid for “literary” stardom (although he did eventually get a story published in the New Yorker) and returned to his roots in science ficiton and fantasy. Over the past thirty years he’s continued to produce intricate and erudite narratives that are mostly ignored by people who think books about sorcery or interstellar travel can’t have lasting value. Among those who know better, he’s been acclaimed in the highest terms. Fellow traveler Michael Swanwick has written, “Gene Wolfe is the greatest writer in the English language alive today. Let me repeat that: Gene Wolfe is the greatest writer in the English language alive today! . . . [A]mong living writers, there is nobody who can even approach Gene Wolfe for brilliance of prose, clarity of thought, and depth in meaning.” Ursula Le Guin, no slouch herself as a stylist and no stranger to the malignancy of literary labeling, has claimed him for the tribe of genre writers by saying, “Wolfe is our Melville.”

The guy who wrote Moby-Dick was dead for thirty years before anyone realized he’d written the first Great American Novel. Wolfe is still around, but he’s 81. Luckily for all of us, Orb Books has just re-released Peace, giving it (finally!) a decent cover and another chance to find the audience it deserves. Get a jump on posterity and read it now.

This post may contain affiliate links.