In the early Dark Ages, if you are willing to believe the 17th century French philologist Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange, Europeans were conducting much of their torture by means of a now-obscure device called the “trepalium,” whose name seems to derive from the Latin words “tre” for “three” and “palus” for “stake.” Illustrations of the device and its uses must be left to the (morbid) imagination, as no reliable images survive, but the word for it lingered, morphing first, according to the OED, into the verb “trepaliare” or “to torture” and soon “to afflict, trouble, harass, weary” before evolving slowly into the more familiar French “travailler” (or Spanish “trabajar”) meaning “to work.” In English, the word’s obvious descendent is the noun “travail,” meaning “hardship;” its less obvious descendents are the noun and verb “travel.”

In the early Dark Ages, if you are willing to believe the 17th century French philologist Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange, Europeans were conducting much of their torture by means of a now-obscure device called the “trepalium,” whose name seems to derive from the Latin words “tre” for “three” and “palus” for “stake.” Illustrations of the device and its uses must be left to the (morbid) imagination, as no reliable images survive, but the word for it lingered, morphing first, according to the OED, into the verb “trepaliare” or “to torture” and soon “to afflict, trouble, harass, weary” before evolving slowly into the more familiar French “travailler” (or Spanish “trabajar”) meaning “to work.” In English, the word’s obvious descendent is the noun “travail,” meaning “hardship;” its less obvious descendents are the noun and verb “travel.”

I relate this etymology primarily because it surprised me. When I looked into the historical journey of the word “travel,” I expected to discover (sorry, linguists) that “travel” shared a common ancestor with “traverse,” from “to go or turn across,” such that early usages of “travel” would necessarily imply continuous motion. I wanted this to be the case so that I could to make a point against Ilan Stavans’s and Joshua Ellison’s irritating New York Times column “Reclaiming Travel,” which appeared on the paper’s “The Stone” blog last week.

The column’s exhortation — that travel should be challenging and meaningful — is heartfelt and not totally lacking in merit. But its blind romanticization of the past (“We have turned travel into something ordinary, deprived it of all allegorical grandeur”) and utter lack of examples of contemporary peripatetic banality robbed it of any resonance. The piece seems to argue, primarily, that today’s travelers expect only pleasure and entertainment from their journeys, while past itinerants (like Odysseus and Moses) were willing to, well, “trepaliare” themselves a bit.

I wanted to suggest to Stavans and Ellison that the period of torture has, in contemporary travel, been reduced in tandem with the dramatic drop in time spent literally “traversing,” or moving from place of origin to place of destination. The banality of today’s travel culture is, then, less the fault of a morally bankrupt traveler than of modern technology. An eight-hour flight might make you feel as though you’re teetering on the hellish edge of Purgatory, but that cramped coach seat is Eden itself compared to, say, a two-month transatlantic journey with you trapped in the shit-encrusted lower cabin of a 17th century carrack constantly bucked on 40-foot storm waves. In his 1984 memoir Boy, Roald Dahl puts the Stavans/Ellison argument better than they manage to do in their column:

“You must remember that there was virtually no air travel in the early 1930s. Africa was two weeks away from England by boat and it took you about five weeks to get to China. These were distant and magical lands and nobody went to them just for a holiday. You went there to work. Nowadays you can go anywhere in the world in a few hours and nothing is fabulous anymore.”

This passage brought much grief to my 10-year-old heart when I first read it. Who, after all, wants to grow up in a post-fabulous age — even one protected, more often than not, from the stench of shit? Who wants to exist in a world bereft of magic? I certainly didn’t, and don’t, and as a fierce opponent (though relatively frequent patron) of airplanes, I’m willing to agree that traveling by air, at speeds almost too high for human brains to comprehend, detracts from the experience of understanding yourself to be somewhere else once you have disembarked from a long flight.

Certainly this was the case for me when, last month, I stumbled out of Fiumicino airport and into the city of Rome. Not long into my stay here, I started experiencing, with some regularity, the extremely unpleasant sensation that I was chewing on rocks, cracking my teeth on them, rolling them over my tongue. Maybe this sensation arose because, not long before traversing the sea, I read Louise Erdrich’s fantastic short story “Nero,” which features a deranged stone-munching canine; or maybe it’s because, not long after arriving here, I actually bit into a pebble that had rudely worked its way into my salad. But I prefer to believe that my stony affliction arose from some misplaced need to “trepaliare” in Rome despite the fact that I was able to “travel” here with very little effort.

Rome is, after all, made almost entirely of stone.

I won’t describe, here, the vast marble churches, the ancient doormat-sized paving stones, the endless sets of smooth-worn granite steps . . . in fact, I won’t even continue this apophasis. You have been to Rome or will go to Rome, and if you aren’t fortunate enough to go you should learn of the city via Hawthorne (please do read The Marble Faun) rather than me. Suffice it to say that stone overwhelms the Roman cityscape in a way that is very foreign and wonderful and permanent-seeming to an American accustomed to wood and steel and concrete.

In her 1994 poem “Matrix,” set in Italy, the American poet Amy Clampitt nails the bizarre feeling that stone, that least-traveling of substances, seems to be the thing-itself of Europe:

” . . . the thing I hankered after was no

rite but a foundation, the bedrockthat survives, the banded strata,

hurled reliquary of the drowned,

remnant of uncountable transformings:

precipice, gray limestone I’ve looked up

into the face of until the looking up

amounted to an attitude of worship:

stone that rings underfoot, whose surfaces

grow populous within doors as a tuned

instrument, eloquent of what lived once . . .”

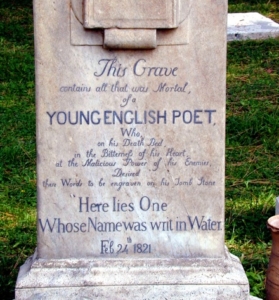

Stone above, stone below, stone speaking the past, or at least you wanting it to — and how better to understand its secrets than to taste it and let it hurt you? It was a book of Clampitt’s collected works that accompanied me, yesterday, to a particular stone located in Rome’s cimitero acattolico, or Protestant cemetery, seeking the eloquence of one who once lived. Her work includes a series of poems that trace the biography of John Keats, who died in a house by Rome’s Spanish Steps at age 25 — my current age, as it happens — and whose remains were confined to a modest grave in a nondescript Roman neighborhood. Keats was one of my first literary heroes. By planning the solitary visit, you might say I was, in Stavans/Ellison terms, “preprogramming” my “emotional voyage.”

And I was hoping to feel something upon passing through the cemetery’s high gates and into its cypress-lined lawn. A bench has thoughtfully been installed by Keats’s gravestone, located in the cemetery’s far corner just by its stucco wall. This bench I shared with a young, silently weeping Italian woman. For a few moments I sat, waiting for something to happen. Outside the wall, traffic noises marked the year: the rush and rumble of motor travel. My benchmate’s companion wandered over and patted her shoulder. I started reading Clampitt.

Suddenly, inches from my ear, a deafening burst of tinny music erupted from a black box fixed to the graveyard wall. The melody was accompanied by a voice informing visitors, in five languages, that the cemetery was about to close. The maudlin melody continued after the international message ended. My benchmate departed. Did I have time to recite “Nightingale?” I tried the first verse. The famed bird’s music clashed horribly with the cemetery’s tinny recording. You were right about mortality, dear Keats.

Following the Jewish tradition, I placed upon the gravestone a smooth pebble, which the cemetery’s keepers would of course remove immediately. My mouth was full of stone and song as I departed the graveyard. I took away nothing. Maybe Stavans/Ellison and Dahl were right, and the ease with which I found the tomb — the lack of travailing via traversing — the lack of smelling the stench — meant meaning lay beyond my grasp. I wish a “but” were coming. If one existed, I imagine it would argue that, unlike stone, words change their meanings quickly, and that the nebulous existence of a machine called the trepalium need not dictate the terms of one’s traveling, seeking, finding, et cetera.

If one existed, it would remind me that Keats, who wanted his stone to read “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water,” knew no place or thing could stay the same long enough to be known by a mere human, however emphatic her petty quest.

This post may contain affiliate links.