In the ongoing discussion about the progress (or lack thereof) of female authors in the literary acclaim-osphere, it’s important to remember that the way we conceive ‘the author’ today is relatively new and rather bizarre. Over the past few centuries, the idea of ‘the author’ has morphed into something more important than the idea of ‘the work.’ And high-literary culture seems more inclined to buy men than women.

So there is an unexamined element in the generally excellent essays of Meg Wolitzer, Ruth Franklin, Roxane Gay, and others who took to their keyboards in response, in part, to the February release of the 2011 VIDA statistics that show nearly every highbrow literary and cultural magazine publishes many more male-authored articles and reviews, and reviews many more books written by men than by women. I’m inclined to agree with these (notably female) reactors, who tend to argue that the literary gender imbalance is a problem, and that the answer isn’t “men write better than women.” But Wolitzer et al. focus more on content expectations — women are seen as more likely to write about “female” topics like marriage and kids — and less on the cult of authorial identity that dominates today’s literary world.

If the obsession with authors is relatively new, the sense of high literature as a boy’s club obviously isn’t. As in most fields, women (beyond the odd eccentric or spinster) didn’t gain entry until the last half-century. The fight for credibility has been tough from the start; it is a continuation of the plight faced by 19th century women novelists. These pioneering writers often wrote under masculine pennames due to what Charlotte Brontë called “a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice.” Brontë’s über-successful novel Jane Eyre, originally published under the masculine name Currer Bell, received much more negative criticism after its author came out as a woman.

More shocking than the gender bias, though, is the fact that in 1847 an unknown author could publish a novel without the public knowing anything of her personal identity. Such a feat would be nearly impossible in today’s world of Twitter and radio/TV/print/internet interviews and author photos and book tours and book trailers and Amazon categories and, generally speaking, branding. In today’s literary culture, the public gets to know the author and the author’s work at the same time. The result is that all ‘literary’ literature published today in America is, to some degree, identity literature.

Well, that is a brazen claim. I’ll need it in order to make the slightly more digestible claim that, given contemporary cultural expectations, it’s harder for women to succeed in an identity-driven literary marketplace. But first let’s rewind a few millennia and from there meander forward through the history of authorship in Western culture, so that we might trace the rise of identity literature.

* * * *

The writers of ancient Rome differed from contemporary authors in just about every way, including two that matter here. First, they participated in the patronage system. Instead of earning a living by selling their literary productions to a general public, poets relied on wealthy patrons who were connected to the Roman ruling bodies. Their works were therefore tied inherently to the state: many early Empire volumes, for example, are dedicated to the famous patron of poetry Maecenas, a close advisor to Emperor Augustus.

Second, nearly all of Latin poetry is self-consciously derived from Greek poetry: narratives, verse forms, and genres were adapted with only minor modifications. Virgil, Horace, and even Catullus were all interested in imbedding their work into the Greek traditions, or in using Greek narratives to tell Roman stories (Virgil’s Aeneid, for example, served as a Roman version of Homer’s great epics).

We might say, then, that Roman poets saw themselves as writing in the service of some sort of glory greater than themselves — the glory of a patron, a state, a literary tradition. The idea of author as original creator, or self-promoting businessperson, would come later.

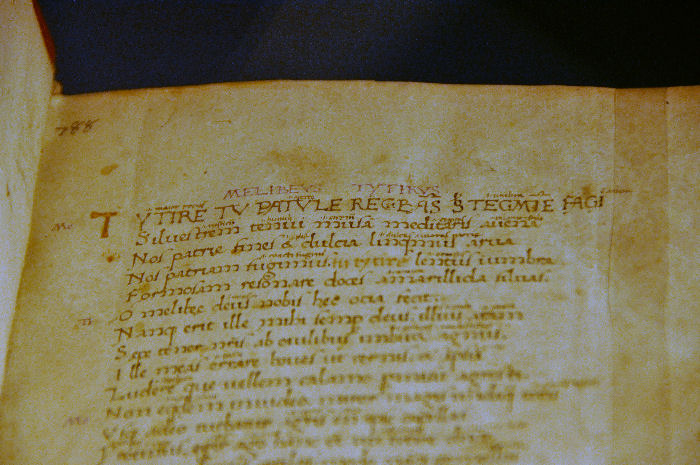

Much later. In medieval Europe, ‘auctors’ were still ensconced in feudal courts, still writing at the behest of the nobility, still drawing their narratives from tales of a distant past. Countless writers took a stab at some portion of the Arthurian legends; many of their names have been lost while their manuscripts survived. We don’t know anything, for example, about the identity of Heldris of Cornwall, narrator and possibly author of the wonderfully wacky romance Silence in which a girl is raised as a male, becomes the best knight in the land, and eventually captures Merlin by overstuffing him with meat and wine (among many other adventures). It’s not that medieval readers didn’t consider authors important, but that they expected them to have ‘auctoritas’ – or moral rectitude and historical expertise – rather than a penchant for original creation.

Even Chaucer, whose name and reputation have survived, based many of his tales on the works of Boccaccio. Even Shakespeare, writing 200 years later, borrowed most of his plays’ plots and substantial snips of their language from earlier works. This much is known about his texts. Yet today’s readers aren’t likely to ask whether Shakespeare was the first writer to use the phrase “To be or not to be” (he wasn’t) because we tend to assume that the words of someone as famous as Shakespeare must be original to him.

Instead, we are obsessed with questioning Shakespeare’s personal identity — about which little is known. Could a glover’s son from Stratford-upon-Avon really have penned many of the greatest literary works in the English language? That’s what the past century has asked of Shakespeare, as any number of books and movies on the topic show. This line of inquiry, this obsession with verifying authorial biography rather than delving into texts, is distinctly modern.

* * * *

This biographical impulse is linked closely with a change in the mode of authorial compensation that was just starting to gain force around Shakespeare’s time. After the 1450 invention of the printing press, owning a physical manuscript, like those produced by monks and clerks in medieval times, gradually grew far less important than owning an infinitely reproducible collection of words — or what we might now call a piece of creative property. At the same time — in the 16th and 17th centuries — the British aristocracy, and with it the patronage system, were beginning to lose some traction. As Europe moved ever away from feudalism towards capitalism, authors began considering new ways to make a living off their works; namely, they wanted to sell copies of their work to the public. Alexander Pope, writing in the early 18th century, is considered the first writer to earn a living from the proceeds of his book sales.

As the monetary value of intellectual property — like Pope’s poetry — became apparent, the need to protect it arose. Thus was born copyright law: legislation regarding claims to ownership of intellectual property, or literally the “right” to “copy” a work. With copyright came the notion of authorial originality. How can an author claim to own a text if he or she has lifted large tracts from literary predecessors, or, to use a modern term, plagiarized? Critic Northrop Frye puts it best: “Poetry can only be made out of other poems; novels out of other novels.” But this fact must be “elaborately disguised by a law of copyright pretending that every work of art is an invention distinctive enough to be patented.”

If we accept Frye’s claim that all literature is dependent on its predecessors, it follows that authors who need to seem “original” might have to carve out an extra-literary niche. Writers of the 18th and 19th centuries hardly neglected their literary heritage, as is obvious from the many translations, adaptations, and retellings that appeared in the era. But they still needed an angle, a way to distinguish their work from that of all the other authors working at the same time. Increasingly, authorial identity became the primary mode of setting oneself apart from the ever-growing competition.

Examples of outsized authorial personalities abound starting in the 19th century. Just consider the outlandishly romantic life of the Romantic/anti-Romantic poet Lord Byron, who melancholically fucked his way around Europe before flouncing off to death in a battle for Greek freedom. Or a letter by fellow Romantic John Keats, in which the mournful young poet claims, “A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity.” It’s a line of argument only worth making in reaction to a culture that did consider poets poetical, and did think that their personal identities mattered in relation to their work.

Of course, in the 19th century it was still possible to put out a successful first novel without giving a single publicity interview. Sir Walter Scott, who published all his novels anonymously, proved this; the Brontë sisters later proved it again. It’s worth noting, though, that in both cases the authors’ lack of identity was a source of intrigue, and that the public very much wanted to know who had written Ivanhoe, Wuthering Heights, and Jane Eyre.

By the time we get to the 20th century, forget it. Authorial identity had become every bit as important as literary output. Consider a few of the era’s most famous English-language writers: Virginia Woolf, known for her privileged upbringing and mental health battles; T.S. Eliot, the consummate curmudgeon; Ernest Hemingway, near-synonym for a certain hunting, hard-drinking brand of masculinity; Sylvia Plath, whose fame followed her dramatic suicide; and J.D. Salinger, whose aversion to celebrity became one of the causes of his fame (the first line of his Wikipedia page claims Salinger is “best known for his only novel, The Catcher in the Rye (1951), and his reclusive nature.”

* * * *

Now we are (finally) approaching the moment when women began entering the workforce in tremendous numbers, and when we — full disclosure: I am a woman — began demanding that our professional contributions be taken seriously. (Remembering the critical success of earlier female luminaries, it is worth noting that Virginia Woolf, revered as she is today, was not widely-read until feminism had taken hold, and that even seeming-icons of feminism like Gertrude Stein wanted to associate their writing with that of men rather than fight on behalf of women.)

In the last third of the century, as Americans were finally grasping the idiocy of the 1950s domestic idyll that inexplicably came to be deemed “normal,” everything was supposed to be changing. My mother, a housewife’s daughter, became a lawyer. From the late ’70s on she endured the requisite taunts and jabs at work, the (false) insinuation that her success rested on an affair with a senior partner, the general sense that she had something to prove.

These were supposed to be my mother’s battles. Indeed, I don’t remember feeling fettered by gender while growing up in the ‘90s and ‘00s. My female friends did well in school and are generally thriving professionally. So it has been incredibly unnerving, over the past few months, to watch various state governments threaten women’s rights and health and to hear, again and again, that women are having a tough time succeeding in the field closest to my heart.

The literary gender imbalance is especially jarring given that women dominate many branches of the literary field — at least the less glamorous parts. My college English classes were filled mostly with women, but were usually taught by men. When I worked in publishing, the office was almost entirely female — except for the exalted editorial department, where the split was even.

While in publishing, where I worked in publicity (and sent many review copies to Ruth Franklin), I observed some of the “women’s fiction” trends that Wolitzer identifies. Novels by women are absolutely more likely to have whimsical, representative covers. Leaving one meeting, during which we picked a cover for a woman-authored novel, I remember another (female) publicist muttering to me “if I have to look at another picture of the back of some girl’s neck….”

I nodded vigorously. Because after a while, all of the lovely-and-sad-yet-strong cover girls looked appallingly similar. It became hard for us to imagine that the stories they contained would vary much either. Book buyers have even less incentive to differentiate among the mass of womanish covers. But as Wolitzer notes, if “women’s” covers tell the same story, then “men’s” covers, more likely to contain all text, to tell no story at all.

When covers fail to differentiate one book from another, how do readers choose what to buy and read?

More than ever before, they — we — choose our books based on the identity of the author. We choose to believe the story, thousands of years in the making, that the author has created a unique work and must therefore be a unique and infinitely interesting person.

* * * *

Here is the problem: our culture still offers men a broader spectrum of acceptable personality types than it does women. Wolitzer quotes poet Katha Pollitt saying “For every one woman, there’s room for three men.” We might amend her statement slightly to say “for every female identity, there’s room for three male identities.”

This notion isn’t new. In his 1734 “Moral Essays” poem “Of the Characters of Women,” our original author-capitalist Alexander Pope claims “In men we various Ruling Passions find;/ In women two almost divide the kind.” If he’s right, then we shouldn’t need more than two women authors, one per passion. Jennifer Egan can be the badass; Téa Obreht can be the sweetheart. Or, since we’re also prone to categorizing authorial identity by race: Toni Morrison can be the African American identity; Jhumpa Lahiri the Indian American one. No one else need apply.

Yeah, fuck Pope.

Or at least get him out of the heads of the literary media, which is more interested in creating and covering big male personalities than big female personalities. As poet Elisa Gabbert pointed out in an interview, having a big personality (read: confident to the point of arrogance or aggression) is still considered an unattractive quality in women, and “women are expected to first and foremost be attractive.” Gabbert added — and I agree — that women shouldn’t have to act ugly in order to prove they’re worth more than their looks. But can you recall any splash-making female voices emerging over the past several years? The highly abrasive Susan Sontag is the last personality I recall leaving a real stamp on the literary world, and she’s hardly remembered as a novelist. People disagreed with her ideas, but they knew her.

The same really isn’t true of even the most successful contemporary women authors — Egan, Obreht, Karen Russell — whose novels critics adored. I can’t tell you what Jennifer Egan thinks about Twitter or birds or cats or — well, you see where I’m going. Jonathan Franzen, whose merest caustic hiccup reverberates through the Internet for days, has practically copyrighted the role of Great American Grouch. As much as people roll their eyes over Franzen’s latest rant against the Internet or eBooks or lollipops or whatever he’s hating at the moment, we also pay attention, as though the act of writing huge, suburban realist novels somehow signals that Franzen’s every gripe against society deserves our ears. We love to hate him, and our hatred serves his reputation better than mild respect serves less vocal (read: less interviewed) women writers.

We pay similar heed to the extra-literary thoughts and identities of Jonathan Safran Foer, Gary Shtyengart, John Updike, and basically every male novelist of both generations mentioned in Elaine Blair’s New York Review of Books post on a shift towards male writers considering their female readers. David Foster Wallace, who coined the term “Great American Narcissists” to describe his male literary predecessors, is himself — still! — the consummate personality of contemporary American letters. Why else, four years after his untimely death, would we still be fawning over the discovery that Wallace (even Wallace!) made a usage error? Why else would fervent fans take up arms when they thought they identified a Wallace-like figure in Leonard Bankhouse, of Jeffrey Eugenides’s most recent novel The Marriage Plot?

Frankly, I can’t understand their complaints because I found Leonard to be a fascinating if exasperating character, and because I’m much more concerned about Wallace’s literary legacy than about the personal one. Like Eugenides and Meg Wolitzer, I’m a Brown alum; unlike Wolitzer, though, I did not like The Marriage Plot because its representations of women dismayed me. Many readers shared my disappointment. The novel revolves around Madeleine, a beautiful reader of novels, and her two potential suitors — the brilliant, cool, volatile Leonard and the brilliant, nerdy, mystical Mitchell. Madeleine comes across as a barely-intelligent hollow vase, filled only by the fictional narratives she adores, whose only important function is to provide a center point for explicating the tremendously rich and interesting inner lives of Leonard and Mitchell. In a novel with such big male identities, there is simply no room for a big female one.

(It’s worth noting that Franzen’s Freedom employs an almost-identical frame: the beautiful Patty, always unsure of her desires, spends hundreds of pages choosing between brilliant bad boy Richard Katz and brilliant nice boy Walter Berglund.)

The sense that women’s personalities are less enthralling and differentiated than men’s seems to have shifted from the real world to the world of fiction. Or maybe cause and effect are reversed: maybe we are more eager to latch on to male authorial personalities in real life because we are so much more used to seeing interesting, fully-formed male characters in fiction. Then again, maybe we are only exposed to those male characters because they so often resemble their identity-obsessed authors.

I don’t see an immediate fix to this problem in literary life, though in literature the solution is for authors to write better female characters. Obsession with authorial identity is not, unfortunately, going to go away — not in this image-and-Internet-driven historical moment, not when authors feel the need to use their personalities as marketing tools. If we’re stuck, at least for now, in a world of clamoring literary personalities, I can only urge women writers to be bold. And loud. And not to cower when loud, bold men respond with the attacks routinely leveled against women who open their mouths. And I can only urge men to listen.

Stephanie Bernhard lives and writes along the Northeast Corridor. You can find her in Amtrak’s quiet car or at @Stephbernhard.

This post may contain affiliate links.