Tom McCarthy is as much a grave robber as he is a writer. And being good at one helps him to be better at the other. If that sounds a little melodramatic, I’m confident that McCarthy himself would take it a step further, questioning the difference between literary creation and the plundering of cultural artifacts altogether. McCarthy’s writing process is to literally exhume forgotten relics and surreptitiously display them in new contexts. Imagine the British Museum and you have a pretty good idea of how McCarthy’s literary output is structured.

McCarthy wrote the nonfiction Tintin and the Secret of Literature in 2006 as an amusing postmodern analysis of Tintin comic creator Hergé’s relationship with his stories and characters. But what McCarthy is really doing in the book is explaining his own literary MO — Tintin and the Secret of Literature is a hidden manifesto. For example, when he explains in chapter seven of the book (a chapter called “Pirates”) the T. S. Eliot and William Burroughs school of the “abandonment of the fetish of originality,” he’s really using them as puppets to explain his own theories. It’s clever — McCarthy is cloaking his ideological stand in the guise of a study, using the voices of dead authors to parrot his own beliefs on the power of the unoriginal. McCarthy’s latest novel to be published in America, Men in Space, is a reproduction, almost to a tee, of the storyline in Hergé’s “Tintin and the Broken Ear.” What’s more is that “Tintin and the Broken Ear” is itself a replica of Honoré de Balzac’s novella Sarrasine. Men in Space is a reproduction about reproductions that teaches us how to read reproductions.

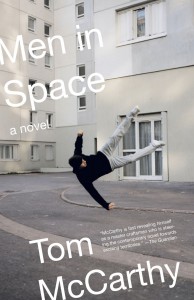

McCarthy isn’t a secret anymore. His first book, Remainder, was published in 2006 to critical acclaim. It made him instantly legitimate, with Tom LeClair even calling him a “young and British Thomas Pynchon.” With subsequent books it seemed like the praise was well earned. McCarthy’s dark historical follow-up novel C proved that in 2010. But fans of McCarthy in America have long awaited Men in Space, published in 2007 in England but only released in America this year. The patient have been rewarded.

Set in Prague during the heady days of early ’90s political transition, Men in Space takes up themes and signs that are familiar to McCarthy readers: art, repetition, counterfeit, systems, misinterpretation, and overdetermination. The story centers around a strange 19th-century icon stolen from Bulgaria and all the people who come into contact with it. There’s Ivan Mansek, the up-and-coming artist enlisted to make reproductions of the work. There’s Anton Markov, a smart Bulgarian family man with Mafia ties and a foot in the art world. There’s a Dutch museum curator, an unnamed secret police agent who may be losing his mind, a British art enthusiast, and a Soviet astronaut stuck in space after the dissolution of his country.

McCarthy is skilled at describing the moments when people see themselves for what they are: individual points positioned in larger systems. One of my favorite moments in Men in Space is when Anton considers his underworld connections:

Anton always wondered how it fits together, how it’s all connected: cells in Sofia and Berlin, Vienna, Istanbul, syndicates in London and the States, parts of a system linked by half-submerged chains . . . Chains and networks, parts all reacting to the other parts, negotiating the steps and swivels of some complex dance. He’s never seen the overview.

The novel is full of these moments — it can be read in terms of the systems people find themselves embedded in. The tenderness of language that McCarthy uses to describe his characters’ experience of these patterns gives his books a warmth most postmodern experimenters have abandoned. It’s necessary to have the individual still experiencing himself as an individual — caught in an incomprehensibly complex mechanism — in order to really convey the loneliness of existing in this overdetermined web of cause and effect. Maybe this is what the title of the book refers to, beyond the astronaut who is literally stuck floating in space.

But these are details you could read in any review of the book. A basic plot outline isn’t enough to understand what the novel is. Which brings me back to Sarrasine, the novella Balzac wrote in 1830. In it, a sculptor makes a sculpture, before his untimely death, of his love la Zambinella. The sculpture is then copied by the men of his killer, The Cardinal, and the fake is deposited in a museum. The fake sculpture becomes the inspiration for a painter named Vien, who copies it, using the woman’s image as his inspiration for Adonis. A copy is made of a copy. In “Tintin and the Broken Ear,” an idol originally belonging to a South American tribe is stolen from a museum by a man named Tortilla, who commissions an artist named Balthazar to create a copy to be placed back in the museum. What Tortilla doesn’t know is that Balthazar has made two copies, passing one off to Tortilla as the original. Again, a copy of a copy.

In Men in Space, the exact same thing happens. Ivan Mansek is commissioned to make a copy of a stolen Bulgarian idol before being killed. His killers don’t find out until later that what they think is an original is also a copy. And so you, as a reader, are reading a copy of a copy. The experience of that realization — the experience of existing in a narrative composed entirely of counterfeits — is the experience of being a character in a Tom McCarthy novel. It’s lonely and invigorating at the same time.

This post may contain affiliate links.