From behind a lemon tree, I watched my ex-boyfriend carefully run an electric razor across the head of a beautiful woman. Her blonde length fell to the grass in long whorls. The woman smiled and laughed as he ran his hands over the fuzzy tracks in her head. The leaves fell, the television flickered behind me, the cops came. When I woke up, I woke up in tears. A week later I read The Book of a Thousand Eyes.

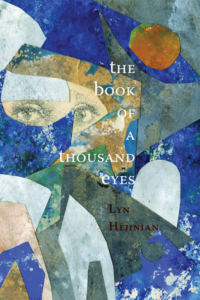

Composed and compiled over the course of the past twenty years, The Book of a Thousand Eyesis the long-awaited magnum opus of Language poetess Lyn Hejinian. She’s been publicly reading selections from this book for nearly as long as she’s been writing it, which has given it a slightly mythical status and an eager cult following. She calls it “my most accessible book of poetry.”

Why shouldn’t she? With its declarative dedication to Scheherazade, the collection works to embody and explore the most pervasive, familiar, and individual stories — dreams. It presupposes no background on the part of the reader in Hejinian’s other work, or in literary or critical theory; it only asks that you have, at some point, dreamed.

For over three hundred pages, Hejinian wanders through waking and sleeping; this placement in a familiarly ruptured landscape helps account for her fractured lines, broken scenes, and abandoned or meaningless characters. Dutifully relaying not only the visceral details of her dreams but also their understood emotional implications, the dreams Hejinian recounts feel convincingly familiar and realistic. In one, she sweeps from a family vacation at a frozen lake to patriotic drumming in the space of a stanza break. “I’m not supposed to be drumming — this is a defiant gesture — but I’m very good at it,” she writes, and the dream, that unspeakably intuitive personal place, is opened for the reader to enter.

Hejinian deftly lines up the experience of this alternative dreamlife with her own critical framework, both as writer and as dreamer. “Isn’t sleep fitted to this world?/ Aren’t dreams a form of internal criticism?” She applies familiar narrative structures to this amorphous landscape in the form of tortured, ill-fitting lessons, or arranges them as fables with no moral and riddles with no answer. Writing quickly becomes equivalent to dreaming until the one effectively nullifies the other. “I’ve been attacked by owls,/ by owls with towels,/ I’ve been attacked/ by snakes with rakes, she writes. It is just this kind of ridiculous language, banal but lacking even banality’s pretense at relevance and sense, that I hear in my sleep; I wake, feeling irritable and depressed.”

This simple equivalence is the collection’s brilliance. In dreams, contiguous morals, rules, or reason are rare. As in my own dream about the electric razor, emotions exist spontaneously, without the weight of sentimentality. In other words, a dream is a naturally occurring narrative that rejects those hallmarks of a ‘successful’ or ‘realistic’ narrative, just as Hejinian’s own corpus of groundbreaking writing has.

This double dance of theoretical negation was all very interesting, but midway through the collection I had to ask myself whether I actually liked it. The Book of a Thousand Eyes is just a blur, full of images and actions that rise and flare, only to be forgotten a moment later. Its dizzying language granted the exact feeling I constantly have upon waking: that I’ve forgotten the point, that what happened is slipping out of my hands, that I’ve learned nothing in all this time. It’s a feeling of loss.

But even in its most compelling moments, The Book of a Thousand Eyes lacks that more compelling moment I experienced beneath the lemon tree in my sleeping mind’s eye — the meaningless shaved head that caused in me such dumb, profound pain that I woke crying. Like Hejinian’s dreams, my own resonated without plot, narrative, or accrued symbolism, but unlike hers it rang out, it shook me to my core. The Book of a Thousand Eyes never documents that magnetic terror, that finality of endless consequence that my dreams, at least, often carry.

But if the collection lacks or glosses over the nightmarish or ecstatic, it’s a conscious choice on Hejinian’s part. After all, this work is not a bedside notebook; the point is not the significance of individual dreams, but a lifetime’s blur of dreams, of the lifelong monotony of waking and sleeping.

Hejinian operates best in such murky, obscure territory. She may have promised nothing, but seems truly to delight in it.

This post may contain affiliate links.