By: Amanda Shubert

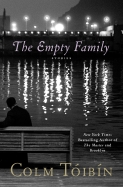

“Silence,” the first piece in Colm Tóibín’s most recent collection of short stories The Empty Family, invents a source for an anecdote told to Henry James by the Irish poet and dramatist Lady Gregory at a dinner party, and preserved in James’ notebook. In Tóibín’s handling, the story-within-the-story becomes a veiled reference to Lady Gregory’s love affair with the writer Wilfred Scawen Blunt, an experience she can only communicate indirectly, through the anecdote and through a series of love poems she writes at the end of her affair and has Blunt publish as part of his newest manuscript. All that emotion rendered in taut little sonnets and squared away on a bookshelf under somebody else’s name—the tidy relinquishing of love to the past and the self to anonymity is typical of the stories in The Empty Family, which also tend to feature loss, the end of love, and a life lived on the margins of experience, or, in Lady Gregory’s case, at dinner parties as the “extra woman [who] was needed, as people might need an extra carriage or an extra towel in the bathroom.”

This not a particularly generous portrait of Lady Gregory, who is not, in fact, known for being the extra woman at dinner parties, but as a major force in the Irish Literary Revival—she collaborated with William Butler Yeats and John Synge to found the Abbey Theater. But, the real Lady Gregory aside, Tóibín’s portrait of love hidden and then lost is surprisingly conventional here and throughout The Empty Family. The stories are divided between two realities—the past, with its illicit passion, and a present reduced to endurance through an empty, unfulfilling life—and though Tóibín moves deftly through foreground and background, his landscapes consist of little else.

Many of these stories are about the way homecoming creates a double of experience, folding time back to reveal an old wound that never healed. In “One Minus One,” the death of the narrator’s mother forces him to recall his father’s death thirty-three years earlier. In “Two Women,” a set designer returns to her native Dublin to work on a film, and a stranger who reminds her of an ex-lover forces her to return to memories she had suppressed. Each story operates through a set of oppositions—past and present, fulfillment and emptiness, presence and absence—and each one moves towards a view of the future in which the only pleasure that can be taken lies in finding comfort in brutal vacancy, relishing, as the narrator of “The Pearl Fishers” puts it, “a long day when the night promises nothing more than silence.”

There’s that silence again, conjoined with emptiness, producing in story after story almost identical portraits of diminished existence. Dublin is always “a grey, empty place” no one wants to return to, love affairs are seizures of animal passion that pass and leave the lovers with nothing but resentment and silence, and the “I” of the stories is invariably detached from its ability to feel, describing itself in daily chores and routines but unable to constitute itself in full. Of the weeks following his father’s death, the narrator of “One Minus One” recalls, “We were emptied of everything, and in the vacuum came something like silence—almost no sound at all, just the sound of sad echoes and dim feelings.”

You’re never unaware of Tóibín’s formal rigor. The stories are jewel-like, polished to perfection, but the prose is likewise hard and cold and fails to reveal a dynamic emotional core. I never found anything beneath this deliberately bloodless writing less formulaic than the rendering of Lady Gregory’s loss, and though there are stories in the collection far more successful than “Silence,” like the novella-length finale “The Street,” each story reconfigures the same basic dramatic ideas. From Dublin to New York, London to Barcelona, from character to character, the emotional content is consistent, and consistently affected and unaffecting.

Maybe it’s because Tóibín only allows his characters one emotion at a time. His characters, retiring from the world or retired from it by loss or pain, often seek a state pure of desire. “I will not fly even in my deepest dreams too close to the sun or too close to the sea,” the narrator of “The Color of Shadows” insists. “The chance for all that is past.” Similarly, Tóibín seems to seek a purity of description. These stories are portraits of single-mindedness, as for Tóibín, purity is not a moral condition but a singularity of intention or experience, the opposite of what Virginia Woolf means in To the Lighthouse when she writes that “nothing is just one thing.” And, like his characters, Tóibín admires silence not so much for what lies beneath it, but for the way it simplifies. The Empty Family may be the mature work of a master, but I didn’t believe a single word of it.

This post may contain affiliate links.