The Blazing World – Siri Hustvedt

If conceptual art often reduces the experience of art to the contemplation of the idea that the art serves to bring into focus, The Blazing World settles for the ideas leading to the ideas leading to the art whose existence must remain imaginary.

Faces in the Crowd – Valeria Luiselli

Aspiring novelist, discerning critic, circular essayist, unabashed prose enthusiast — any one of a writer’s identities, his or her separate selves, has something to say about a great book. Perhaps that, right there, is what makes great books great: engaging all selves at once.

I feel like cardboard. My God! Vice leaves a bitter taste. Virtue brings sweet consolation. Alcohol does me untold damage . . . but I am always so thirsty!

The end takes a grotesque psychological turn that reminds you that environmental devastation, perhaps especially during our fleeting period of history, is as much a psychological issue as any other.

[Niceties] is the rare exception in which the term poetic used to describe fiction isn’t hyperbolic. The stories feel like prose poems because they operate according to associative logic and sonic pleasures.

Women Who Make A Fuss – Isabelle Stengers & Vinciane Despret

What is the value of walking soberly and honorably to the guillotine? Why not cry and scream all the way there?

Every Day Is for the Thief – Teju Cole

As much as I like reading Cole online, the experience of reading his work in a big chunk is sharper and feels more complete.

What Would Lynne Tillman Do? – Lynne Tillman

Fiction writers’ opinions on current events have a basic, ironic appeal: Credentials, qualifications — they have none.

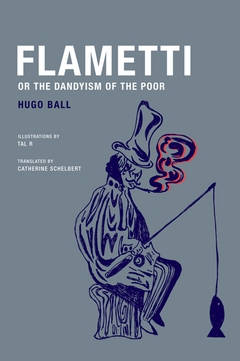

Flametti, or the Dandyism of the Poor – Hugo Ball

It is not often I read a novel so enthusiastic and unconstrained (and so funny) in its use of language and in its building of worlds.

Travel Notes (From here — to there) – Stanley Crawford

The logic here is Kafka’s, one emphasizing powerlessness, comedy, and terror. And like Kafka’s, it’s a logic Crawford often locates in the formal structures of speech, the way language can seem to contain crucial information even when it’s actually just bunches of barks and wind.