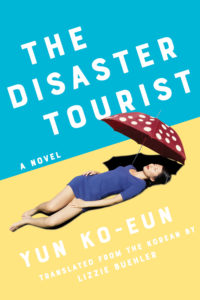

[Counterpoint Press; 2020]

Tr. from the Korean by Lizzie Buehler

The Disaster Tourist is a novel about routes: the path through the Pacific of items dislodged from Jinhae by a recent tsunami; Yona Ko’s daily commute on the ever-growing Seoul subway system; the descent from her twenty-first-floor office to the lobby, which often involves getting groped by her boss in the elevator; her journey from Seoul to Mui, an island off the coast of Vietnam, following her boss’ offer of a free trip in lieu of hush money. As Yona remarks in the novel’s beginning: “Travel [is] nothing more than the recognition of the path [we are] already on.”

When we meet her, Yona’s careerist path is a familiar one, though in its specifics, it is less so. She designs travel packages to natural and manmade disaster zones at Jungle, a disaster tourism agency. Though Yona is privately fascinated by issues of loss and memory — “like where rocks that fell off the side of a mountain ended up,” or “the scales removed from a filleted fish, or unwanted potato sprouts, or even bullets” — she carries out her duties with cold, efficient professionalism. Yona is “skilled at quantifying the unquantifiable,” a helpful trait in her industry. Jungle is a cutthroat organization, however, so when her boss begins assaulting her regularly, she is mostly concerned for her job. After all, everyone knows that this man only targets corporate “has-beens.”

Yun, a Korean short story writer and novelist, expertly satirizes this “devoted employee” archetype. Though Yona is undoubtedly a product of global capitalism, we can also trace her ancestry to Nikolai Gogol’s Akaky Akakievich: an absurdly committed worker who, after one-too-many encounters with a merciless system, becomes a ghost. Yun, like Gogol, centers her satirical project in the voices of her characters. Though it’s hard to retell a joke with the lightness of its first delivery, translators do this all the time, and Lizzie Buehler (who is, full disclosure, a friend of mine) is particularly good at it. For instance, when Yona meets with an HR rep to talk about her boss, Jo-gwang Kim, the rep replies teasingly: “Oh, Jo-schlong!”

After this brush-off from HR, Yona is expected to disappear. Kim offers her a free trip to Mui in exchange for a report on the travel package, which is up for review. Yona finds herself with four other Korean tourists — a mother and daughter, a recent college grad, and a writer — and a local guide. Yun’s characters are vivid. Most of us know a recent college grad who says things like, “My friends all want to go see museums or castles, but I don’t care about those things. By the time our trip ends, I want to be inspired to live dynamically.” Or a frustrated parent who says: “Kids nowadays — they grab a snow crab, pull off the legs, and expect there to be cooked meat inside.”

As the group tours the island, the marks of disaster tourism prove little different from those of tourism in general: inequality, racism, and uncompensated emotional labor. Mui’s attraction is its 1963 massacre, when the Kanu tribe attacked the Unda and a sinkhole opened to swallow the corpses. One evening, the tourists choose whether to overnight with an Unda or a Kanu family. The next morning, the massacre is reenacted for their entertainment. As local children hawk trinkets, Yona realizes that her camera is gone. She makes an accusation that she is later embarrassed by.

The tourists deaden their new, unsolicited class consciousness with alcohol. Yun, however, refuses to let the reader off that easily, instead revealing the off-stage lives of Mui’s impoverished citizen-performers. Boys with the most pitiful expressions are recruited to work in the homestay villages; after their tears dry up, they are replaced. When Yona reencounters a street musician she had seen during her tour, the old man gives her an angry glance and says, “Please. We need time off, too.” Yona also sees the woman who hosted her overnight and graciously painted her nails; now, off stage, she treats Yona coldly.

Class is something we act out, and, in The Disaster Tourist, Yun satirizes those who write the script. The citizens of Mui must perform for their livelihoods but, as Korean tourism to Mui dwindles, business leaders and tourism industry workers begin a new draft of this script. These power-hungry playwrights are cruel to their actors, but Yun is more interested in poking fun at their bad writing. Kitschy, heart-wrenching stories are used to conceal exploitation, just as exploitation itself has become banal:

The writer was currently fleshing out every possible fact about Mui’s future victims. He didn’t need to be very creative, considering how eagerly people read stories like this, but he did have to decide who would die. The writer’s notebook contained dozens of pre-determined casualties. A mother and son, an engaged couple, an elderly husband and wife who’d lived in harmony their entire lives, a family whose newborn baby was spared, a teacher who died saving her students, parents whose young child survived, an old dog that dashed into the chaos to save its owners.

Yun lambasts the uninspired, overdone narratives that the least privileged are commissioned to play.

By the novel’s end, she also punishes the script-writers’ hubris, as the uncharted paths of tides, winds, and seismic energy converge to annihilate their carefully revised script. This destruction finally makes room for the islanders’ truth: “They had no rehearsals and no compensation, but their stories flowed to the ocean like blood from a head wound.” Not only has the curtain fallen on their act — the stage has been destroyed.

But back to our protagonist. As Yona extends her trip and uncovers greater horrors, she still cannot shake the ghost of Kim. Yun describes Yona’s reaction after a phone call with her boss: “For a moment, she had forgotten that Jungle mattered more than Mui, that her office could be scarier than this island.” The author poignantly shows how abuse can haunt a survivor’s experience of the world. On Mui, Yona is often unnerved by the intimacy of motorcycle rides: “As she clung to Luck, Yona realised that backs have faces. How strange that a single movement could make her, and someone else, feel so awkward.” What’s more, the island’s forbidding corporate hegemon is called Paul. The first few times people mention the company, Yona mistakes it for a powerful man.

Perhaps it is Yona’s focus on her identity as a woman that obscures Mui’s insidious powers from her view. Because, in fact, it’s unclear whether Yona ever fully comes to consciousness. At one point, she realizes that she, too, is victim to capitalism’s penchant for quantification. After giving Mui’s travel package a bad evaluation, Yona hesitates; as a “has been” at Jungle, “she felt empathy for this D-rated programme.” More often, however, Yona struggles to recover her compromised professional status at any cost. She thinks: “The people of Mui needed tourists. Jungle needed tourists, and Yona needed tourists. As long as this plan succeeded, Yona would promptly return to her original job at Jungle, and maybe she’d even rise up to Kim’s level, or be assigned a position where Kim couldn’t bother her.”

Through Yona’s moral limitations, Yun demonstrates that feminism without radical class politics is void. The author’s single blunder is her decision to undermine this nuanced message with a trite love story between Yona and a local. Though this relationship teaches Yona about the islanders’ backstage lives, it never fully awakens her to Mui’s systematic exploitation of the poor. On a narrative level, this love story baselessly celebrates Yona for crossing the class barrier. She may love one local, but she never fully comes to terms with her role in perpetuating the inequality on Mui. This is a crucial distinction that is smothered by the syrupy tone of the lovers’ scenes. The love story, then, is another narrative of liberal tolerance that ultimately promotes the ideological reproduction of class inequality.

Granted, it’s difficult to write a compelling literary opprobrium of capitalism. Love stories, like capitalism, celebrate the experiences and feelings of individuals. However, Yun has demonstrated that scripts can be edited. It would have been possible to narrate Yona’s emerging class consciousness without invoking romance. Yun could have even imagined the Mui citizenry as a character, imbuing it with the same vividness she gives individuals in the novel. In short, I wish Yun had written a new literary script, one that reinforced her own radical message.

Still, readers who enjoy cleverly critical thrillers will find this book hard to put down. It’s also hard to forget. After all, as Yona points out, escapism is never total. The scariest part of reading The Disaster Tourist is the creeping recognition of ourselves in Yona: even at capitalism’s worst, we continue playing along in order to save ourselves.

Fiona Bell is a literary translator and scholar of Russian literature from St. Petersburg, Florida.

This post may contain affiliate links.