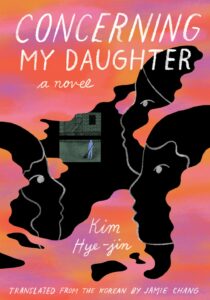

[Restless Books; 2022]

Tr. from the Korean by Jamie Chang

Concerning My Daughter is a tightly structured, carefully crafted novel. The English translation is beautifully accomplished by Chang. It is just over 150 pages, in which no word, symbol, metaphor, or nuance is wasted. Award-winning novelist Kim Hye-jin opens and closes her novel with a meal and a funeral to read as parallel experiences. Over this short novel, the reader travels alongside the mother as she attempts to bridge the chasm separating her from her daughter, Green. The mother clings to a traditional and worn-out understanding of family and familial commitment: the one man–one woman paradigm. She also struggles with a cultural value that encourages silence and conformity rather than active resistance or contradiction. It becomes all too clear that the mother’s journey is difficult, not just because she refuses or is conceptually unable to understand her daughter’s choices, but because the basic facets of Korean society have failed. Contingent labor is on the rise, the aged are stowed away and neglected at a profit, and there are no protections for the LGBTQ+ community. How do you fight a society’s ills while keeping a low profile and not jeopardizing some elemental aspect of your well-being? The mother suffers extreme inner turmoil when she confronts her daughter’s life. As she questions her daughter’s choice to protest the status quo, the mother also questions her own role as a bystander.

Throughout the novel, the heat is a visceral presence, both night and day. A blinding sun accompanies the mother on her different errands. It is paired with her loss of appetite, her intensifying aches and pains, and her growing inability to restrain her anger toward her daughter’s choices. At the climax of the novel, the mother, her daughter Green, and Green’s life partner, Lane are all ill or wounded when Green’s university protest event is attacked by a thuggish mob. This scene takes place during a torrential and blinding rainstorm. The reader can’t help but experience the mother’s struggle and its physical impact on her body and psyche. As the novel’s crisis peaks, the heat subsides, the mother’s appetite returns, and she has crossed the chasm dividing her from Green, even if she has not fully embraced the implications of standing on the other side.

Kim addresses significant societal failings in Concerning my Daughter. The setting for the novel is South Korea, but it could be set almost anywhere. The mother’s precarious economic condition as an aide in a nursing home is shared by her coworkers, including a single mother with an aging parent also in care, and by the mother’s tenants, which includes an unhappy family of four. This portrayal of life on the highwire of disaster demonstrates the limited protection of a weak social safety net. Perhaps at a different point in history, such as the time of the mother’s childhood, those in need, early or late in their careers, aging parents and relatives were supported by closely knit families or communities, but in a society of isolated individuals, the holes in the net are much too big to provide protection or security.

This weak net is even more apparent due to the growth of a contingent workforce. In the early pages of the novel, we read, “My daughter doesn’t have a steady job. People who work but have no position—the number used to be one in ten, then three, and now six to seven in ten. People with no positions are eligible for nothing. Not for loans, not for public housing.” This piece of data is crucial to the novel because both the mother and daughter are part of this contingent workforce. The mother, in her 70s, as a temporarily employed caregiver and her daughter, in her mid-30s, as an adjunct faculty member.

This safety net has holes much too large for the elderly. At the nursing home, the mother witnesses firsthand that decisions are driven by a corporate focus on profits rather than quality of care. The mother is filled with fear about her approaching old age. She has only her daughter as a potential source of care and support. But Green continues to depend on her mother for financial support because of her low-paid position.

The mother’s fear and antipathy are exacerbated by the fact that she believes her daughter refuses to live a “normal life,” with a husband and children. The mother cannot accept that her daughter’s life partner is a woman. It is horrifying to her and we see her horror played out in her body. This comes from the mother’s ingrained inability to see Green’s relationship with her partner Lane as the foundation of her daughter’s family, and by extension, the mother’s own family—and, indeed her desired support in old age. The mother does not want anyone—her neighbors, coworkers, church group—to know about Green because she believes it is shameful and the shame will reflect on herself.

The mother-daughter relationship is at the heart of this novel. Green’s partner Lane represents an ever-present antidote to the mother’s fears—if only the mother could see beyond her prejudices. Lane embodies nurturing: She has been with Green long enough to have supported Green throughout her father’s final illness. When Green was unable to be in the hospital with him, Lane was there and with Green at her father’s funeral. After Green and Lane move in with the mother, Lane cooks healthy foods and tends to the mother even as the mother openly reviles her. She is the committed family that the mother wishes for her daughter. The mother is blind to this in her obsession with what she sees as the abnormality of the relationship. But Lane and Green resist the mother’s animosity and, in their own distinct ways, persist.

As the mother struggles with her daughter, she develops a growing sense of responsibility to the aging patient, Jen, who led a life of good works, notably in the United States away from South Korea. She never married and never had children. As the mother thinks of it, Jen inexplicably devoted her entire life to strangers and now pays the price by being alone and without family. Kim leaves the why of Jen’s self-imposed exile unexplained, but the reader can imagine that Jen may have been gay and it was easier for her to live away from her family and society’s prejudices. Moving to another continent may have provided an easier path from the one that Green and Lane have chosen. In one passage, the mother contemplates that when some parents discover that their children are gay, they “threaten their children. They put a bottle of pesticide in front of them and suggest they drink it and die together. Some actually kill their children and die with them.” While the mother doesn’t condone this, she later imagines that if her husband were alive, he would not have “had the strength to cope and might have killed our daughter instead . . . he would have chosen to pretend she never existed in the first place.” The mother does not wish to see her own daughter die, but she does imagine killing Lane, even as her daughter tells her that “Lane is not a friend. To me she’s husband and wife and child. She is my family.”

The mother finds Jen’s choices as incomprehensible as her daughter’s choices, but at the same time admires Jen for her travels and independence. Still, Jen has ended up in care and as her memory and connection with the present fades, the nursing home’s commitment to her care fades. The mother feels a strong responsibility toward Jen despite being pressured by the nursing home to cut corners in ways that affect Jen’s health.

Jen’s care and the mother’s conflict with her daughter interweave as the mother discovers that Green is involved in an ongoing protest over the unprovoked firing of adjunct professors likely because they were gay, and allegedly because they incorporated the topic of homosexuality into their lectures. The mother asks Green whether this should be her business and accuses her of choosing to stand out. Green assures her mother that this is her business, “it could happen to me, too, at any time. And I’m not alone.” Green’s choice to take a stand begins to influence the mother’s thinking that translates into her need to continue caring for Jen regardless of what is decided at the nursing home and regardless of whether she loses her position. Here, the mother jettisons the role of bystander.

The mother, urged by Lane, forces herself to witness Green’s continued protests. As she observes the violence and mindless hatred that her daughter and her cohort of protestors face—many of whom are not directly affected by the firings because they are not gay—the mother’s perspective slowly alters. Her concerns for Jen collide with her awakening to her daughter’s predicament. As the mother’s involvement with Jen and Green increases, her physical condition deteriorates as the weather continues to intensify. She resolves to rescue Jen, echoing her daughter’s words, “this could happen to me.” The mother recognizes that her motivation could be selfish: “This isn’t the ‘way of the world,’ but my business. My business that is waiting at my doorstep.”

As the mother’s understanding of her daughter grows, she finds she is unable to resist Lane’s unwavering patience and caring attention. The mother’s aches and pains are debilitating and her appetite is gone. Lane, who has also been wounded amidst the chaos of the protests, brings herbal tea and muscle relaxant patches for the mother and herself. They tend to each other’s wounds, creating a moment of communion that recalls the Last Supper. This is a transcendent moment of mutual care. Lane becomes the mother’s business, marking a clear turning point in the novel.

As Green continues her protests, the mother makes a mad plan to rescue Jen from the distant dementia center, to which she has been discarded. Lane becomes a crucial part of the plan, stepping in for Green at the last minute. Once Jen is rescued to the mother’s house, Lane and the mother care for Jen until Jen’s death. The novel then comes full circle as the mother, Green, and Lane carry out Jen’s funeral. Green takes on the role of chief mourner, usually carried out by a male member of a family. The coming together of the three women to see Jen through her life’s final rites symbolizes their metamorphosis into family.

In the meal that opens the novel, the distance between Green and her mother is apparent and growing wider. At Jen’s funeral, as the three women—Green, Lane, and the mother—become family, the mother looks at the unappetizing funeral food, tastes it, and, significantly, finishes her entire bowl. She urges the girls to join her. Like the moment of communion earlier in the novel, this moment again reflects the Biblical last supper. But for the mother and her daughters, it is not the last supper, but a first. The mother will continue to struggle with Lane and Green’s relationship. She imagines that acceptance will take a miracle: “[M]aybe what lies ahead is a life of endless fights and tolerance. Will I be able to take such a life? Will I get through it?” At the very least, the mother now has the desire to understand and to accept. She has stepped into the midst of their lives.

Rebecca Stuhr is an associate university librarian at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries in Philadelphia. Her academic background is in literature and music performance and her career as a librarian has centered on collections, outreach, and engagement. She has reviewed fiction and literary studies for several library review journals.

This post may contain affiliate links.