This essay was first made available last month, exclusively for our Patreon supporters. If you want to support Full Stop’s original literary criticism, please consider becoming a Patreon supporter.

“Crossing Parallel(s)“

In 2016, Arch Out Loud, an architectural research initiative dedicated to the exploration of contemporary social, geopolitical, and spatial issues, hosted as part of their Open Ideas category a design competition challenging civil engineers and artists to model an underground bathhouse in the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Given the active geopolitical complexity of the DMZ as a site, and the cultural significance of public bathhouses in South Korea as theoretically egalitarian social spaces, along with the structures’ semi-absurd relegation to the underground, the competition offered a unique hypothetical arena within which to generate innovative designs.

The implementation of these models in the actual DMZ, of course, was neither anticipated nor pursued. The competition’s hypothetical/conceptual/speculative scenario—posed as a “dilemma”—was designed to motivate proportionately creative “solutions,” even though none of the submissions are physically conceivable because the space that hosts them forbids it. Indeed, the speculative nature of the designs is fundamental to their existence: they are founded upon, and charged by, their impossibility.

That the bathhouses were mandated for the underground can be thought of as a literal undermining of the DMZ’s geopolitical function, a direct questioning of how deep the DMZ’s demilitarization runs. In the same way that migratory cranes that fly over the transboundary zone are technically trespassing through legally restricted airways for aircraft, an underground structure or installation asks whether the status of war/ceasefire applies to subterranean spaces. How far into the air does the U.N.’s jurisdiction extend? How deep down? If the literal dimensions of war zones cannot be defined, can their ideologies claim space?

Because humanity in the flesh is prohibited within it, the DMZ as a domain not only compels but also in a sense, in its current state, requires speculation. In the nearly seventy years since it settled (more or less) on its present form—a 4-by-250-kilometer buffer zone demarcating North and South Korea—the DMZ has evolved as an ecological and theoretical habitat. In the past twenty years, it has gained attention in the humanities for its capacity as a venue for artistic reflection and experimentation, particularly in the visual arts. And this attention is not limited to Korea and its diaspora. Arch Out Loud’s highly international competition evidences and contributes to this growing interest and, importantly, frames the DMZ as a necessarily multidisciplinary subject.

In the artist statement accompanying their winning design, entitled “Crossing Parallel(s): Bathhouse as a Metaphorical Theater,” Jinhyun Jun, Minkyung Song, and Kangil Ji of STUDIO M.R.D.O. & Studio LaM in New York City put it this way:

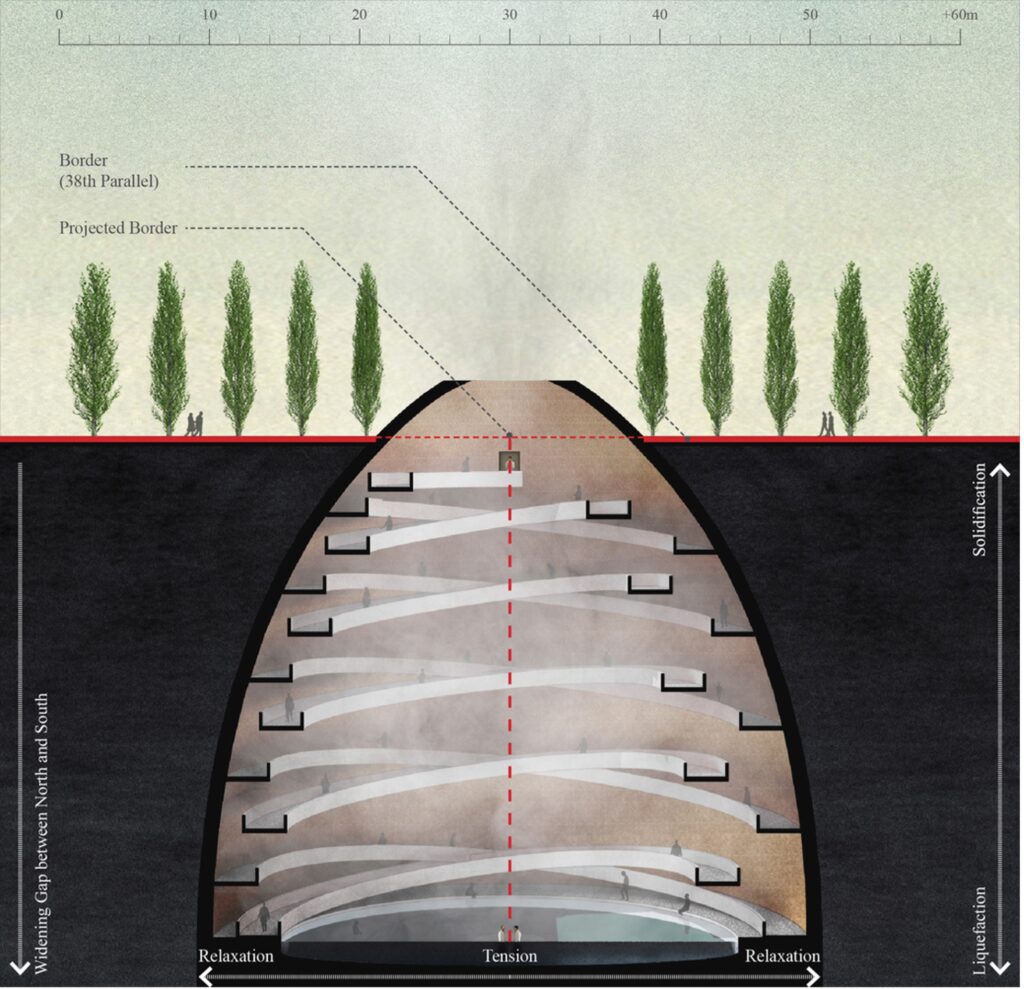

[The] thirty-eighth parallel is not a thin superficial line, rather a thickened situation: it has been solidified by accumulation of ambivalent emotions – tensions and relaxations – between North and South.

The DMZ’s multifold dimensionality is central to the staging of Arch Out Loud’s dilemma and to the studios’ winning proposal. The borderland attracts attention for its concentrated nature, this “thickened” quality, and is often characterized in terms of its many statistical densities (i.e. “the most heavily militarized border on the planet”). The thickness is also a strangeness that sets the space askew from the nations it demarcates. On the one hand, there’s the sense that time within the DMZ stopped when it came into being, that demilitarization removed it from the ideological forces that could develop, destroy, or otherwise manipulate its terrain; on the other hand, the DMZ as a time capsule is also actively warping, quasi-living insofar as it hosts tremendous biodiversity relative to its surroundings. Set against one hyper- and one under-developed nation, then, it is both alienated and controlled, a variable that not only mediates but also exaggerates, or dramatizes, the peninsula’s decades of divergence.

Meaning, the act of staging bodily encounters, particularly male, in the DMZ is inherently charged with instant military implications. So much so that this appears to be one facet of the artistic challenge Arch Out Loud constructs: how to put sufficiently delicately, how to bring together without overreductions, the profundity of Cold War stasis and collapse in the form of a public bathhouse. For the winning designers, this meant embracing and even centering the dramatic and abstract dimensions of the DMZ explicitly.

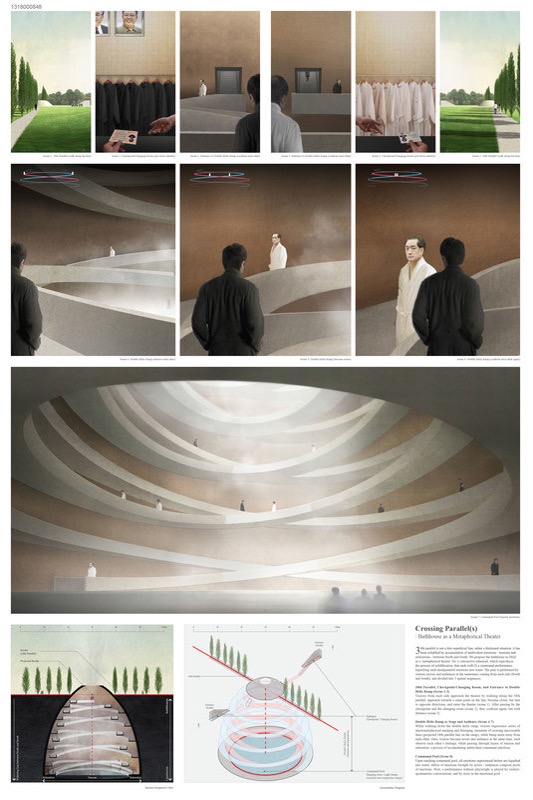

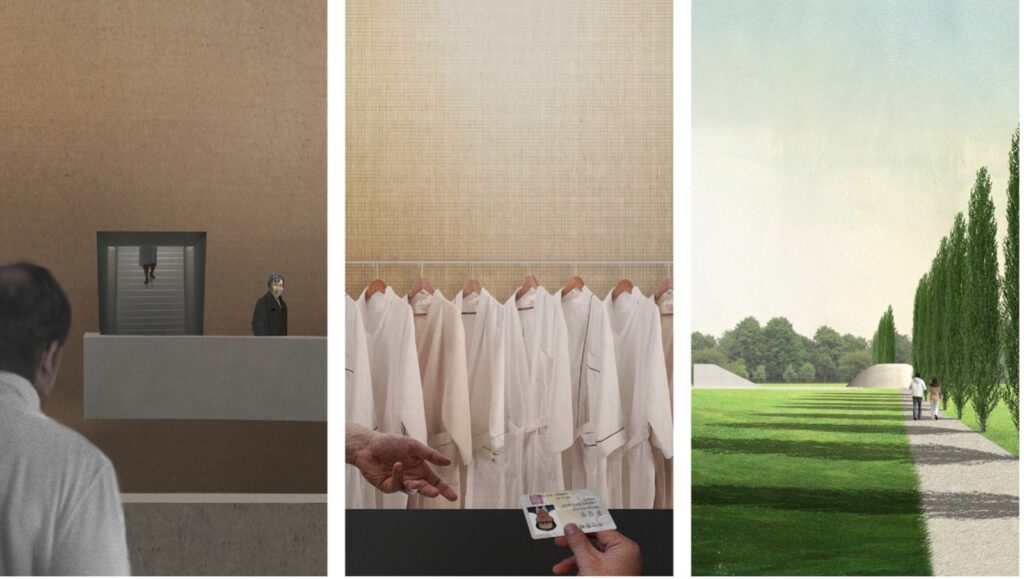

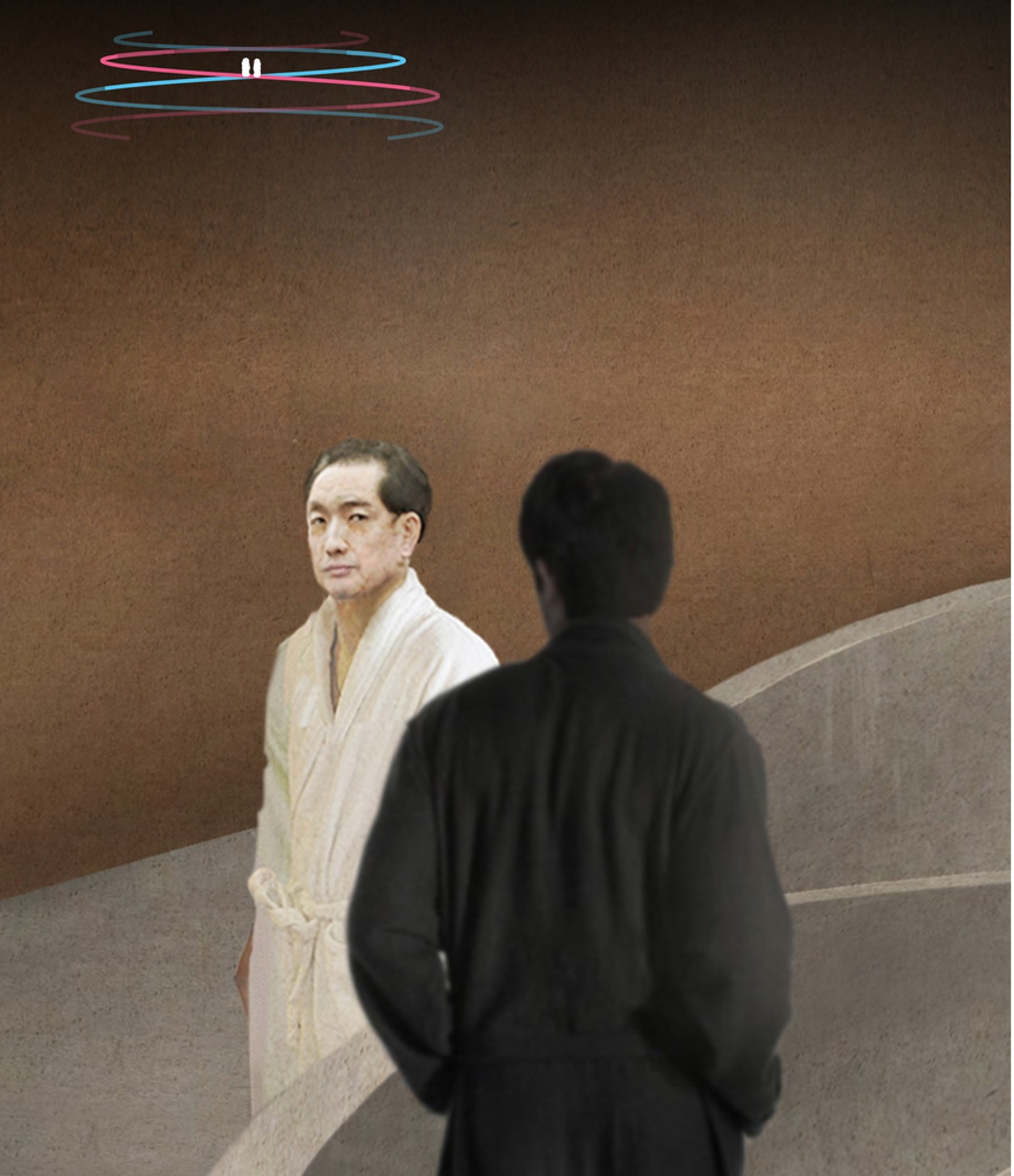

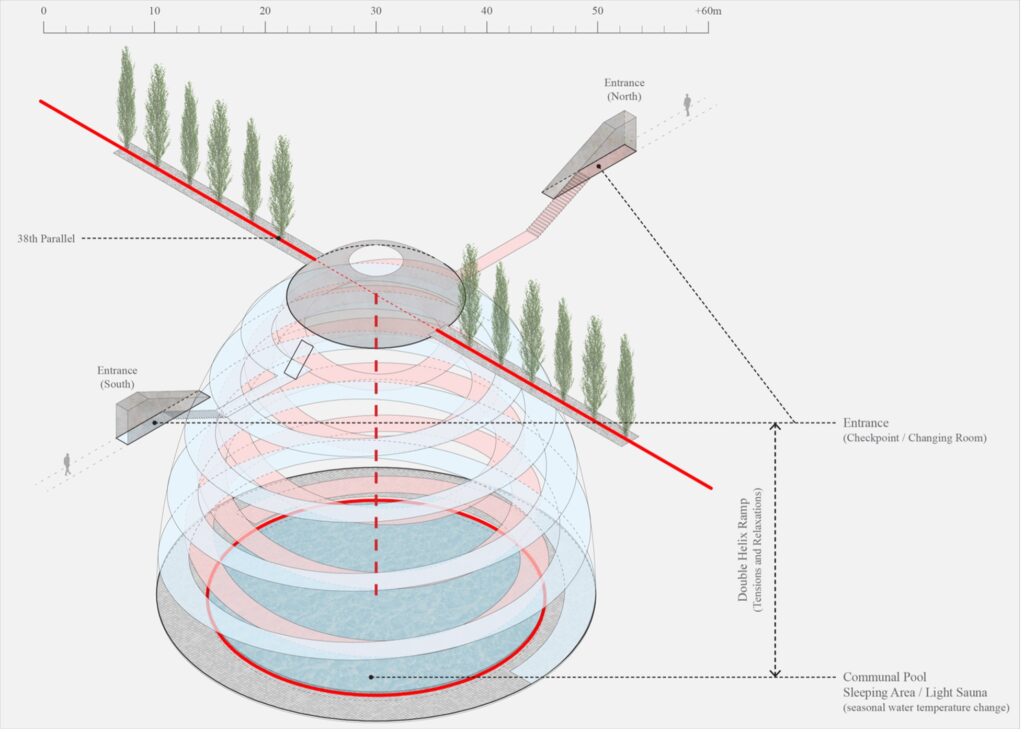

A man enters the “metaphorical theater” according to his nationality, dressed in what might strike a viewer as garb inviting moralization, if not militarization: South Korean entrants wear white bathrobes while North Koreans wear black ones. The portraits of Supreme Leaders past and present queue us into this in the northern lobby. Both parties appear male and present IDs. There is something between serenity and solemnity to the mirror triptychs depicting these procedures. By the long shadows cast by slim, pruned trees along the footpath of the southern entrance, we can tell it’s early morning.

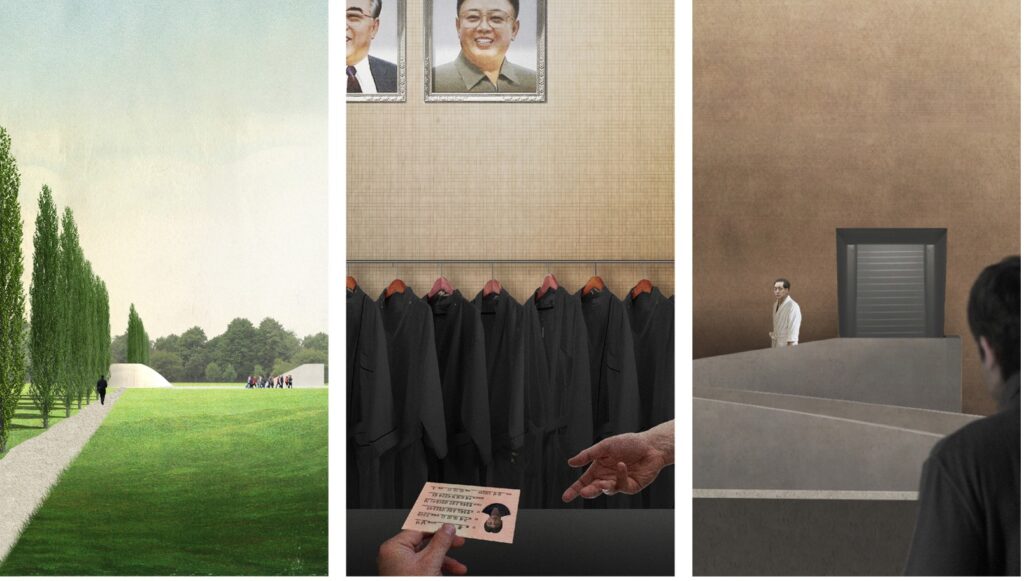

Inside, on the double helix ramp that descends into the common pool, it’s unclear how the participants keep their cardinal bearings, or if orientation relative to the above ground is part of what the ramp unspools. Daylight from directly overhead spotlights the middle section of the structure, but the focus of the journey downward is on the human actors’ interactions. The architects describe the emotional physics in this way:

“In the proposed bathhouse, represented as a ‘metaphorical theater,’ visitors (actors/audiences) coming from each side reproduce the process of such solidification while walking down the double helix ramp; experience of merging and diverging, moments of crossing uncrossable lines, while being more away from each other. Upon reaching the communal pool, all such experience is liquefied into water, and debris of emotions brought by visitors soaks into each other’s skin.”

The double helix ramp stages a descending continuum of human drama towards an ultimate idealistic “liquification” of all tensions in liquid communion. The trope of parallelism, alluding to the DMZ’s approximate position along the thirty-eighth parallel north, is entertained rather than confounded through the oblong interactions between the entrants, who assume the roles of opposing forces. The assumption that the actors would descend at simultaneous rates, thus pitting themselves against one another at regular intervals, is as idealistic as the conclusion of complete ideological conformity/dissipation in the pool, but the thought experiment is important for how it structurally conflates encounter and impasse just as unification and dissipation are conflated underwater: each moment the two actors “cross paths” on the ramps, their paths don’t actually cross; only their gazes meet, or are inclined to. The interaction, in other words, is held apart as much as it’s forced together, the parallelism preserved insofar as there is no actual intersection, only the suggestion of emotional trespass.

This kind of magnet play, as it were, casts and recasts the same scene we impulse towards at any border. The face-off trope is perpetuated, by degrees widening, towards its simultaneously quasi-spiritual and politically underwhelming resolution. The actors are forced into dramatic and precarious proximities only to be guided away towards their original prescriptions as polarized actors of political and ideological states. Then the cycle is cut by entry into water, and we are supposedly freed of the purgatorial loop.

At first glance, the insider’s view of the bathhouse from the pool resembles the interior of the Guggenheim, or maybe the mythic “Pit” in the Batman movies. One can’t help but feel entombed by the underbellies of the ramps, which are sidelined in the shadows as if shying from the natural light. That light anoints the pool water with a heavenly aspect you might expect of a slit in a crypt.

A cross section of the bathhouse, reminiscent of geological cutaways of rock, shows the axes along which the actors’ degrees of tension and relaxation cooperate towards the pool. From this vantage, their descent appears to perform an unscrewing of the bullet-shaped cavern that looks to be lodged upward rather than downward into the ground. Tension, moreover, is literally centered in the bathhouse, or perhaps by the bathhouse. Insofar as tension is a measure of human proximity to that axis, two figures standing face to face in the pool at that centerfold, as depicted in the above image, have neither escaped that tension nor fully succumbed to it. The liquid conclusion of their descent doesn’t resolve that center axis so much as offer a new axis—the vertical trend towards widened engagement—by which to read against it, to minimize the primacy of the tension line.

Which is to say the success of the bathhouse is its dynamic irresolution. It articulates the grooves of the DMZ’s paradox, that of progressive spatial peace that clings to an axis of tension if not terror, and dramatizes the possibility of encountering impasses as forms of perpetual encounters. The ramp demonstrates the repetitive human dramas that animate our understanding of what is largely static in space: even the pool itself is a temperate, climate-controlled pool (the DMZ is home to these kinds of thermal springs), but then again, temperate pools are subject to mild fluctuations. In other words, what stays still is subject to circulation; what moves remains as if still and constant in the scheme of its movement.

“Cranes“

Even before the DMZ was technically the DMZ, when it was still a suppositional form fluctuating in accordance with the violence that prescribed it, it was an arena for human drama. Written on the heels of the Korean War in 1954, Korean writer Hwang Sunwon’s short story “Cranes” is set in a nameless village along the thirty-eighth parallel north, the latitude that famously approximates the DMZ today. Separated by the war some years prior, two childhood friends, Songsam and Tokchae, meet again post-armistice as members of opposing political factions. Having fled to the South when North Korean forces took control of their village, Songsam returns as a public security officer following its reclamation by the South. Tokchae, on the other hand, unwilling to abandon his aging father and farm, stayed behind to become a de facto communist, and incidentally the Vice-Chairman of the Farmer’s Union. When Songsam encounters Tokchae being held captive in the village, awaiting escort to a Southern city for capital punishment, he offers to take the prisoner there himself.

The two men leave the village together on foot, in silence, Tokchae bound by a rope. Songsam chain smokes moodily behind him, privately recalling their childhood mischiefs, like rolling cigarettes with pumpkin leaves and stealing chestnuts from a neighbor’s tree. Eventually considering that Tokchae is likely craving a smoke, Songsam decides to abstain for the duration of their walk; but he does this rather than offer Tokchae a cigarette, perhaps the more obviously humanizing gesture in their situation. Rather than address their encounter or activate it further, he preserves their impasse. Their mutual recognition is inevitable, though, and soon, Songsam, suddenly outraged, asks Tokchae accusatorily how many people he’s killed as a communist in the intervening years.

It’s the only moment in the story that betrays Songsam’s moral stake in what would otherwise seem like an arbitrary political association with the South. It’s also here that the two make eye contact for the first time and the much-awaited faceoff seems most imminent. But Tokchae’s non-answer diffuses the expectation for an accompanying ideological showdown. At first, he merely glares in Songsam’s direction, ostensibly recognizing him and the personal edge to Songsam’s assumptive question. Songsam’s outward anger persists as he presses Tokchae for a straight answer, but the broken silence relieves something in him, the narration tells us. Indeed, it’s as if Songsam’s relief emboldens his interrogation of Tokchae, like he’s roleplaying the angry interrogator while internally pleased to be dialoguing with his old friend.

What comes of it is neither an outright denial nor an admission of guilt on Tokchae’s part. Rather, Tokchae offers a somewhat lame explanation, a kind of excuse: that is, there is no explanation; he has no excuses. As to why he didn’t flee when Songsam did, they are the same reasons he didn’t flee this time and was found hiding in his own house. Namely, his father is aging and unwell; he’s bound to his family and land. As for his title, Vice-Chairman of the Farmer’s Union, Tokchae suggests that whatever it implies about his politics was ascribed to him by the party who had claimed the village. As far as he’s concerned, his occupation as a farmer is the extent of his identity. For whatever else, the war, that behemoth abstraction, is to blame.

If not already fully apparent, Songsam and Tokchae’s acute maleness surfaces in the discussion that immediately follows, about Tokchae’s marriage to a woman nicknamed “Shorty.” Songsam recalls Shorty chiefly in terms of her physical attributes, with a mix of fondness and distaste—a wry misogyny intended to signal the survival of intimate knowledge between him and Tokchae, and therefore the possibility of reviving their friendship. Obviously problematic to a contemporary reader, misogyny here salvages male fraternity. Hearing that Shorty and Tokchae are expecting a child, Songsam suppresses a strange laugh, a near outburst that signals, whatever its moral character, Songsam’s humanity rattling the binary political frame.

It’s at this juncture that the two men arrive at “the so-called demilitarized zone,” a field at the foot of a mountain, where Songsam spots a flock of cranes. He at first thinks they’re human farmers hunched over in labor, a double take that conjures to mind the human presence that has since left the zone—that is, cranes, traditionally symbols of longevity, are here ghostly gestures to displaced people, or ciphers for diaspora. The nostalgia of earlier passages reaches a forte as Songsam recalls how as kids, he and Tokchae captured a red-crowned crane in this same field. They kept it bound and played with it (though that play could be interpreted as torture). But when they heard one day that a researcher from Seoul had come to their village to hunt a crane as a specimen, they rushed to the spot where they’d been keeping it hostage to release it. If a crane was to get shot that day, it wouldn’t be theirs.

Despite at first being too stiff and weak to spread its wings from having been bound for so long, the crane ultimately flew off just in time, unharmed. The researcher was evidently in the field with them at that very time and fired a shot at it but missed. Emerging abruptly from his recollection of these events, Songsam then suggests to Tokchae that they go “crane hunting.” He unties Tokchae and, without further explanation, crawls off into the brush, leaving Tokchae standing there unbound but caught off guard, registering the roleplay for what it is: an opportunity to flee.

성삼이가 불쑥 이런 말을 했다. 덕재는 무슨 영문인지 몰라 어리둥절해 있는데, “내 이걸루 올가밀 만들어 놀께 너 학을 몰아오너라.” 포승줄을 풀어 쥐더니, 어느 새 잡풀 새로 기는 걸음을 쳤다.대번 덕재의 얼굴에서 핏기가 걷혔다. 좀전에, 너는 총살감이라던 말이 퍼뜩 머리를 스치고 지나갔다. 이제 성삼이가 기어가는 쪽 어디서 총알이 날아오리라.

“Hey, let’s go crane hunting!” Songsam spoke suddenly. Tokchae looked puzzled, wondering what he was talking about. “I’ll use this to make a noose. You go and drive the cranes.” He untied the rope binding him and went striding off through the grass.

Given how quick and suggestive this moment is, Tokchae’s hesitation is reasonable. But even assuming that he just as quickly apprehends what memory or set of memories Songsam is alluding to, the allusion is still abrupt and uncontextualized for Tokchae, who doesn’t share the reader’s knowledge of Songsam’s interior; the allusion doesn’t mandate a clear course of action.

Of course, the scramble for a role in the wake of the stage direction is ultimately beside the point. Songsam’s prompt is less about following a playbook or actually identifying allegorical roles in the moment as it is about assigning new metaphorical ones—about identifying roles as metaphorical. The proposed roleplay is a decoy that both makes possible and conceals the actual human drama of Tokchae’s escape precisely by superimposing onto their actions the notion of their mutual acting. Anything they do in Songsam’s proposed schema, in other words, is purely figurative (he implies), a curtain behind which a real political transgression/liberation may play out as if incidentally.

Still, the possibility of Songsam playing “hunter” and hunting Tokchae, appears to at least cross Tokchae’s mind as he recalls the nearing probability of his political execution:

대번 덕재의 얼굴에서 핏기가 걷혔다. 좀전에, 너는 총살감이라던 말이 퍼뜩 머리를 스치고 지나갔다. 이제 성삼이가 기어가는 쪽 어디서 총알이 날아오리라.

Tokchae’s face paled abruptly. The thought flashed through his mind that a little while before the men had said he would be shot. In a moment a bullet might come speeding from the direction where Songsam had gone striding off.

Though it was the soldiers holding him hostage back in the village, and not Songsam, who alluded to the firing squad, Tokchae envisions the possibility of that particular fate: the bullet coming from where Songsam stood. Whether or not this signals mistrust between them is unclear, but the thought is at least indicative of Tokchae’s recognizing the interpretive precarity of his situation: The consequence of misunderstanding Songsam’s motivations is potentially fatal. Songsam, however, quickly quells this fleeting doubt in the next sentence, as he urges Tokchae to take the cue (to escape), upon which Tokchae goes wading off into the brush. He walks ostensibly not after Songsam, but in a different direction, towards freedom—at least in the immediate sense. “Just then,” the story abruptly ends, several cranes in the field take flight.

The pictured confluence of the remembered cranes and the diegetic ones in this final image—the blurring of their particularities and collapsing into a totally singular, yet totally plural metaphor for both loyalty and freedom—folds them over what would appear to be a temporal axis. Again, as with their first diegetic sighting in the field, the cranes—or “the crane”—is a cipher for an absence, for gone people, and now for an escaped Tokchae.

The complex staging of this dramatized escape, though, and the strangeness of the fact pattern framing it, is easily overlooked or enveloped by the concluding image. Merely skimmed or read in terms of existing commentary, it would be easy to summarize the events in the field as Songsam “turning a blind eye,” setting aside his political loyalties so his friend can achieve political freedom: that is, choosing his loyalty to Tokchae over loyalty to his state. In this view, the cranes are a blunt metaphor for that political freedom, the sky a free zone. But this freedom is not guaranteed by the text. The cranes draw the scene upward and into themselves, perfectly ambiguously, into a tropic open ending: Even if Tokchae escapes in the field, where will he go? He could quite plausibly get captured again. That he has escaped his state of superficial capture does not mean he has escaped his state of political capture. The more significant accomplishment in the field, I suggest, which the text does procure, is that the act of Tokchae’s escape was a jointly executed endeavor by him and Songsam, a rhetorically unifying or binding, rather than liberating or releasing, act.

Consider the three events in the story involving cranes: the first two are distinctly historical while the third is a convolution—a simultaneous recasting and remixing—of the first two:

Tokchae and Songsam capture a crane (as children);

Tokchae and Songsam release the crane, to save it from the hunter;

Tokchae and Songsam “capture a crane,” to save “the crane” from “the hunter” (years later).

Between the second and third events is the permeable event of war and the distinct event of Tokchae and Songsam’s separation, which the third event in the field, mediated by “the crane,” saves or salvages by reestablishing Tokchae and Songsam as joint actors in a moral universe. Viewed from this parsed vantage, one perceives an allegory wherein “the crane” is humanity and “the hunter” is the state, but again, more important than the ideological content of the performed play is what is forced into place by the nature of their performing: that is, their playing together. Songsam’s staging of the escape as a memory game or cosplay realigns him and Tokchae as unified actors in that game, regardless of the game’s outcome. The crane/s do not just metaphorize the triumph of human loyalty over politics but also serve as rhetorical diversions that reorganize the subjecthood of the drama’s actors into a picture of united agency against all else. That is, Songsam and Tokchae—and, indeed, the cranes, by training our eyes up and away from the event of “the crime”—become conspirators against their respective states and collaborators in the creation of an imagined stateless state within the DMZ, which is necessarily and ironically poised against the politics that conscribe it.

“The DMZ”

Reading “Cranes” through the lens of analysis, in the narrative or historic present tense, generates a dissonance resembling the simultaneity of encounter and impasse in the underground bathhouse: the contemporary reality of the DMZ meets but never replaces the state of the diegetic borderland, which was less defined as a space in the story’s day than ours, so more fluid and less regulated, but also less “wild.” Looking back through nearly seventy years of demilitarized activity, or militarized inactivity, one wonders, is Tokchae’s freedom only possible within the DMZ? Would it undo itself should he leave? That is, was the DMZ the only absolute condition of his freedom, the necessary frame for the story’s plot?

Surely, Songsam’s staging their role play in that field (within the “so-called” demilitarized zone) was strategic, but what was a vacated blind spot in the military complex of the story’s day is the very axis of tension in ours. All eyes are on it now on either side. The DMZ of then was tenuously wedged between battle fields, not governed peace zones. It was the space between foci, not the center line of conflict. That Songsam could simply escort Tokchae by foot along or through it in the story alone signals that the nature of that zone is different than the one in our contemporary reality. To trespass the DMZ today would militarize the trespassers and the zone itself. It’s only by retroacting our conceptions of the DMZ, which have evolved since “Cranes,” onto the historical present of the act of (re)reading it, that we feel like we’ve accessed internal irony about the borderland that has grown between our moment and Hwang Sun-won’s.

If Tokchae’s escape is like a crime that occurs in the audience of a theater when the lights are dimmed—that is, not in plain sight, but in our laps—it seems that the DMZ as a setting provides the necessary conditions, namely the simulated darkness, the adequate absence of human witness, for that crime to play out. Where exactly the boundaries of the “crime scene” fall, though, is unclear, because the scene on stage (in the field), the performance that steals our witness as readers (“the game” of hunting the crane), partly mimes the very crime it helps create space for. In our metaphor of the theater, it’s as if our actors were on stage alluding to the crime while it plays out in the audience, blurring diegesis: Let’s perform a memory to release us from our present, the logic goes, superimposing the past (remembering “the crane”) upon the present (hunting “the crane”) only temporarily so as to veil the present’s blatant secret, the present’s presence.

Just as “the crane” in the story signaled something diegetic and historical, and arguably even functioned as the very thing conflating the two or allowing us to toggle between those signaled moments, “the DMZ” today—the “so-called” DMZ—in the context of our reading “Cranes,” is both DMZs, the one in the story and the one in our world, as well as the abstract entity, “the DMZ” running between them, that timeless symbol of division, simultaneously spanning and separating then and now. Indeed, cranes still migrate to the fields “Cranes” gestures to. The DMZ as reality keeps the underground bathhouse impossible, therefore possible, imaginable, and necessary to imagine. The static is animate. The Cold War is frozen, but the planet is warming, I say from an arm’s length, with the removal of analysis, in the historical present, the historical performing the present in a spiral.

Note: The cited English translation of Hwang Sunwon’s Korean text is by Brother Anthony of Taizé. For the sake of clarity and consistency with my commentary, the diacritics from his translation have been omitted from Songsam, Tokchae, and Hwang Sunwon’s names, and both texts have been presented in block form.

Jed Munson is a Fulbright scholar to South Korea.

This post may contain affiliate links.