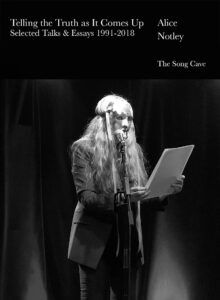

[The Song Cave; 2023]

What is a book of talks, a book of talking? As a form, what is the talk doing? What are the layers of time incubated in a talk that’s now found itself back on the page? Writing written to be talked, then talked, then booked, then read. Spanning from 1991 to 2018, Alice Notley’s collection of talks, Telling the Truth as it Comes Up, is an expansive, roaming, meditative portrait of the poet’s mind at work and play that helps us work through some of these questions.

I’ve been thinking about talking for a while. I’m curious about it as a form, a space for improvisatory, informal, unfixed attention. At its most receptive, talking surrenders to the whim of the present moment that infiltrates its fleeting course. In other words, talking happens in time, as time. Unfixed, it develops as a motion through thinking that may stumble upon—or into—a truthfulness otherwise unknown.

Writing, by contrast, often attempts to evade time, to rise above it and assert the power to shape its reality. Writing takes time. It is not, conventionally speaking, tangled up in time in the way talking is. Mulled over, fretted over, and revised, a piece of writing can stabilize itself from the instability of the present. Writing proposes completion, whereas talking remains unfinished.

Wrestling at the intersection of these two time zones, the “talk” is a funny form. In the move from verb to noun (from talking to the talk), this genre mixes the flexibility and unfinishedness of talking with the reflective, containing proposition of writing. There is the talk parents feel obligated to have with their prepubescent children, the “we need to talk” talk with a partner. And then the talks like the ones that fill this collection, given by academics, writers, and artists at universities and cultural centers for students, readers, and the general public. A “talk” rides a line Notley rides even harder: between the consciousness of the writer per se and the unconscious of the talker, between the known and unknown.

Over the course of this collection, we listen as Notley openly participates in the present tense of her thinking. A celebrated experimental poet and thinker, often associated with the Second Generation New York School poets, Notley is known for the shapeshifting language of her epic poems, including The Descent of Alette (1992) and Mysteries of Small House (1998). Telling the Truth as It Comes Up is the first time readers are offered a comprehensive account of Notley talking.

Across these pages, she wanders by way of resonance and attention through an expansive range of subjects: from detective novels, to the Trojan War, politics, the writing of husbands, friends, sons, reflections on dreams and process. Notley demonstrates a particularly capacious wingspan in her thinking and the language she encounters through it. Thinking with her is a movement that occurs in response to the rhythms of time in coordination with the unconscious. She is attentive to the wind of the present tense, letting the course of her thinking veer, open, and digress, in the continuous process of becoming itself.

“I’ve lost track here,” she admits near the end of “The No Poetics, or The Woman Who Counted Crossties,” a keynote speech delivered at the Free University of Brussels in 2013. “I’m counting tracks, just counting crossties. I don’t know what anyone should be doing,” she continues. “There are no shoulds. But I do want to lead everyone invisibly on these tracks somewhere that is fabulous, not just adequate.”

Notley rides time, gets lost in it, finds herself again. Her talking is stunningly unpossesed of itself—radically unattached to subject-matter and at the same time deeply sensitive to it. What accrues in the movement of her thinking is a deep ethic of humility and trust in the encounter with the present moment as it arises. “I believe in time as in the mind of god,” she declares in her “Alette Update 2013” talk given in Paris, “though I don’t believe in god, except to think that we are all godlike.”

For Notley, truth does not lie hiding in some secret recess. It comes up; it occurs over the course of time, over the course of thinking and living and their telling, if one manages to remain open enough. This argument—that truth lives in time rather than on top of it—is a radical epistemological perspective that unfastens truth from the fixity of its position and reintegrates it into the instability of a living moment. “The poet’s job is to unsay Fate,” Notley writes in her 2002 talk “The Iliad and Postmodern War,” asserting the poet’s task of countering permanence.

In what feels like the collection’s seminal talk, “Instability in Poetry,” which Notley delivered in 2001 at Temple University, she hones in on this ethic of openness by way of a couplet from her poem “City of Tingling”: “Come with me amid this instability / permit me not to know what things mean yet.” “What things mean” here, Notley suggests,

refers to the elements of what is taken for reality, it refers to the notion that we have created the world we perceive, by limiting how much we perceive and by defining how we perceive it. The lines hope for a poem with enough holes and slippery places in it for another way of perceiving or being to leak in, thus the poem is not terribly interested in keeping track of itself, because it doesn’t want to be another system.

Notley is acutely aware of the violence of system-making, the will to define, contain, and control. Her discussions of poetics develop in tandem with the critique of political systems of control and domination. The ethics, and poetics, of instability here are political, embodying a way of receiving the fluidity of what is alive. Notley writes against these systems that attempt to “settle” what is and is not and sever the body—of meaning, of personhood, of the public, of the text—from its potential in becoming. War is one such system that preoccupies Notley. Writing of the Vietnam War, which her brother fought in, the Iraq War that spanned eight years of this collection, and the literary Trojan War, Notley presents war as a system dedicated to the “preservation” of meaning through control. “Do we need the definers after all?”

Over the course of these talks, we have the pleasure of riding with Notley through time, moving with her, and listening as her thinking uncovers itself before us. Her genius is in her openness to what comes. Once again, we encounter Notley as one the great interlocutors of the world, a dedicated advocate for what is between and beyond definition.

Tess Michaelson is a writer and multidisciplinary artist based in New York who works at the intersection of text and performance. Her writing has appeared in motor dance magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, Cost of Paper, and Chicago Review, among others. She is currently at work on an improvisational novel.

This post may contain affiliate links.